9 Craziest Skydives of All Time

Look out below!

On Sunday, Oct. 14, 2012 Austrian skydiver Felix Baumgartner successfully attempted his wildest stunt yet: becoming the first human to break the speed of sound in freefall in the highest skydive yet, from 23 miles (37 kilometers) in the air.

Baumgartner's jump, broke a record set in 1960 and topped his previous high jumps of 71,581 feet (21,818 meters) and 96,640 feet (29,460 m). But Baumgartner isn't the first daredevil to vie for skydiving supremacy. Here are nine of the most daring, dangerous and sometimes fatal jumps in history.

Wingsuit stunt

British daredevil Fraser Corsan is hoping to break four world records with two daring jumps: the highest altitude, highest speed, furthest distance and longest time flown in a wingsuit. Corsan will make the jumps from a high-altitude hot air balloon at 40,000 feet (12,100 meters). [Read the full story about Fraser Corsan]

First to leap

The idea of the parachute is an old one — Leonardo da Vinci sketched a design for a pyramid-shaped one in his notebooks — but it wasn't until 1797 that a brave skyjumper made the first high-altitude leap from air to ground. That year, balloonist Andre-Jacques Garnerin rose 2,000 feet (610 m) above Parc Monceau in Paris in a hot-air balloon, cut the balloon free and descended back to the ground attached to an umbrellalike silk parachute. [Gallery: Leonardo da Vinci Drawings]

It was not a pleasant ride, according to Smithsonian National Air and Space Museum. These rigid early parachutes oscillated wildly on their descent. One account of a later jump in England describes the parachutist as "extremely pale" and taken with "a short sickness" after his leap.

First to die

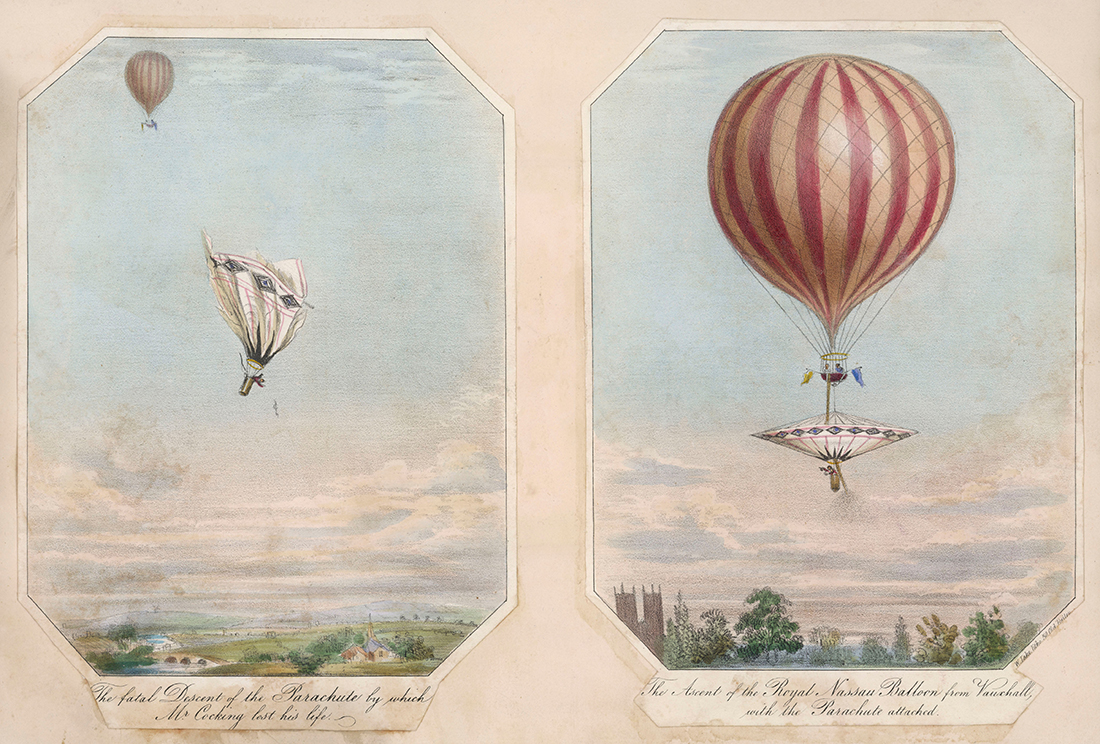

Parachute technology was bound to improve from these first rigid, unsteerable designs. Unfortunately, not everyone would survive the progress. In 1837, Englishman Robert Cocking, a watercolor artist, tested a cone-shaped parachute of his own design, believing it would be more stable than umbrella-shaped designs. It was not.

Cocking stepped off a hot-air balloon with his parachute at about 5,000 feet (1,500 m) near Greenwich, England. He'd failed to properly calculate the weight of the parachute, however, and the whole apparatus plummeted faster than expected before turning inside out and breaking apart. Cocking's body was found in a nearby field. (Shown here, the first hot-air balloon flight with passengers in 1783.)

From an airplane

By the early 1900s, skydivers were ready to up the ante by leaping from planes instead of balloons. There is some controversy regarding who took the first leap: Career parachutist Grant Morton gets credit from some, who say he jumped off a Wright Model B in California in 1911. A better-sourced claim is that of U.S. Army Captain Albert Berry, who definitely parachuted from a Benoist pusher-type plane over St. Louis on March 1, 1912, according to the Smithsonian National Air and Space Museum. [10 Most Outrageous Military Experiments]

Berry and his pilot, Tony Jannus, took the boxy, rectangular-winged plane to 1,500 feet (457 m). Berry climbed out on a bar dangling underneath the plane's nose and leapt. He fell 500 feet (152 m) before his parachute, trailing behind him, engaged, and he later reported that he flipped head over heels five times midair.

Ladies first

Georgia Ann Thompson Broadwick was a small woman (at only 5 feet tall, her stature earned her the nickname "Tiny"). But her parachuting feats were anything but. In 1907, Broadwick saw a hot-air balloon flight at a traveling carnival and instantly caught the flying bug. She convinced the carnival owner to hire her and train her, and she was soon parachuting over state fair grounds nationwide for the benefit of awestruck crowds.

After becoming the first woman to parachute from an airplane, Broadwick caught the eye of the U.S. Army, who asked her to demonstrate how parachutes could save pilots from midair disasters. In 1914, during one of these demonstration jumps, Broadwick accidentally became the first person to perform a free-fall jump when her static line got tangled in the airplane's tail.

Static lines are ropes attached to the airplane that get pulled taut when the jumper leaps, dragging the parachute from its pack and automatically deploying it. Up until this time, all jumpers used static lines. But when her static line malfunctioned, Broadwick jumped anyway, free-falling and manually deploying her chute. The leap made her the first parachutist ever to jump free-fall.

Broadwick gave up jumping in 1922 and took a job on a tire factory assembly line to make ends meet.

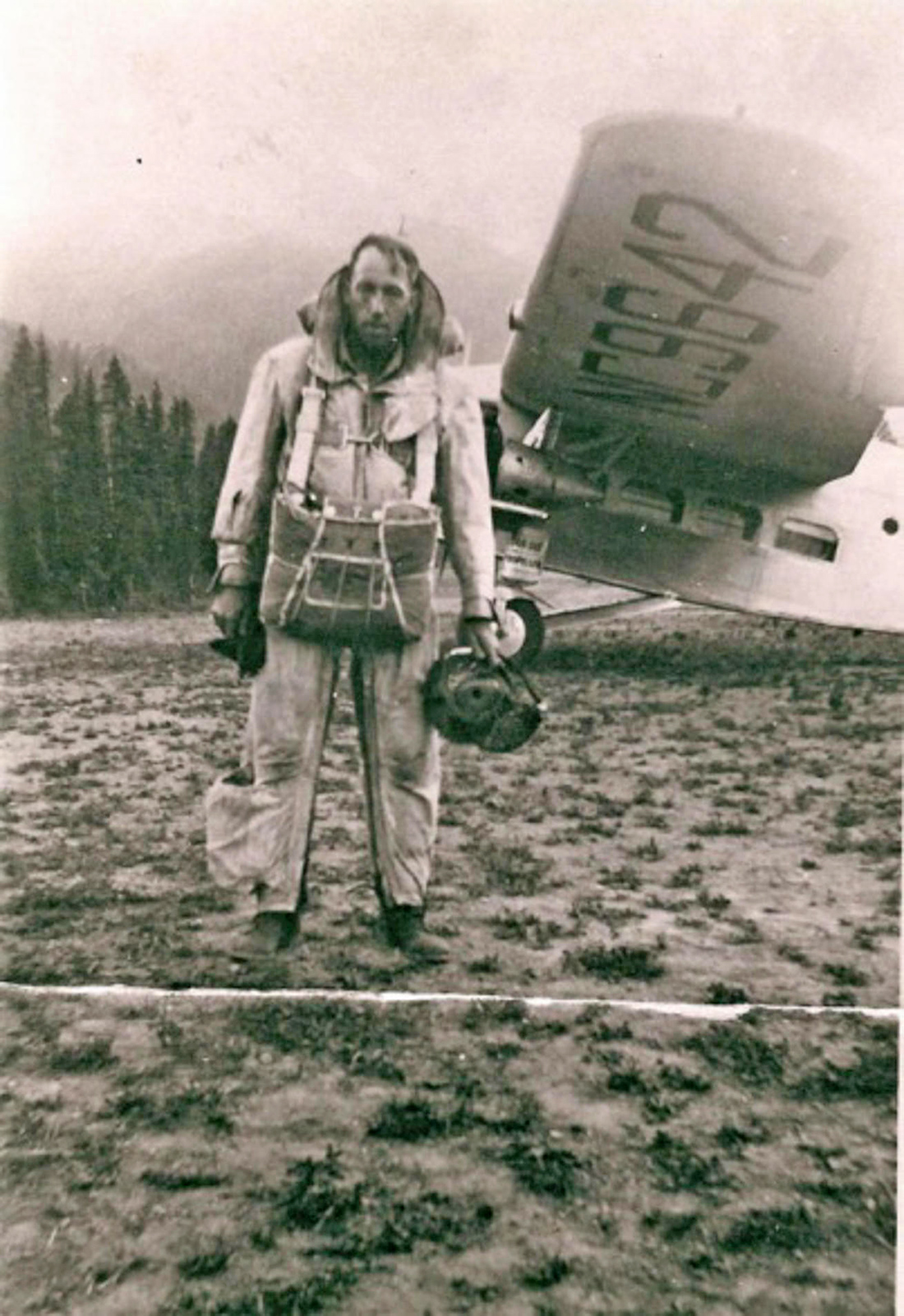

For recreational parachutists or carnival performers, the jump is the main event. For smokejumpers, however, the landing is just the beginning. Once on the ground, these men and women have to fight remote wildfires with only the equipment dropped to them by parachute.

Into the fire

More than 270 smokejumpers work in the United States today (Russia also has a large smokejumping program). The job was unheard of, however, until the late 1930s, when the U.S. Forest Service first began training young men to leap into fires that couldn't be reached any other way.

On July 12, 1940, two men put this training to use as the first smokejumpers to parachute into a blaze in Idaho's Nez Perce National Forest. Rufus Robinson was the first out the door, followed soon after by Earl Cooley, according to a 2009 obituary of Cooley in the Washington Post.

Cooley made a death-defying landing, his parachute's lines tangling midair before unwinding; he hit a spruce tree on the way down, but emerged uninjured. The first two smokejumpers extinguished the fire by the next morning.

Highest jump

As jets began to fly higher and faster, the military became concerned about saving pilots in the case of high-altitude disaster. To find out what the human body was capable of, Capt. Joseph W. Kittinger Jr. jumped three times from dizzying heights: once from 76,400 feet, once from 74,700 feet, and finally, on Aug. 16, 1960, from 102,800 feet (23,287 m, 22,769 m and 31,333 m, respectively).

That last jump still holds the record for highest and fastest human fall. Kittinger fell freely for 84,700 feet (25,817 m), reaching a speed of 614 miles per hour (988 km per hour). Thirteen minutes and 45 seconds after he stepped from his balloon-supported gondola, Kittinger was safely on the ground in Tularosa, N.M.

"It was definitely beautiful, but it's also hostile," Kittinger told the New York Times in 2008, recounting how his right hand swelled up to twice its normal size during the jump because his pressurized glove did not work properly.

High-altitude accident

Indeed, Kittinger's successful leap did not spell safety for everyone trying such a stunt. In 1962, Soviet Air Force Colonel Pyotr Ivanovich Dolgov attempted a jump from 93,970 feet (28,640 m) as part of a project testing a new pressure suit. Dolgov's visor hit the gondola from which the man leapt. The suit depressurized, and Dolgov died before he reached the ground.

Supersonic plunge

A suit disaster is one of the dangers Baumgartner could have faced in his Oct. 14 attempt to break Kittinger's record. Baumgartner made his jump from nearly 128,000 feet (39,000 meters) above the New Mexico desert. He reached speeds of 833 mph (1,342.8 kph) before deploying his parachute, breaking the sound barrier. [Photos: Baumgartner's Practice Jump]

Baumgartner previously completed two test leaps from 15 miles and 18 miles (24 km and 29 km). Among the risks he faces in these extreme jumps are shock-shock interaction, an explosive interaction caused by shock waves colliding; flat spin, a situation in which Baumgartner could spin horizontally, forcing blood to his eyes and brain; and excessive, out-of-control speed. Low pressure and frigid temperatures create additional dangers. And then there's the landing. If Baumgartner falls unconscious during the jumps, his emergency parachute will automatically deploy, according to the Red Bull Stratos team, which managed the attempt. But an unconscious parachutist can't maneuver himself around obstacles on the ground or slow his speed, which could make for a rough return to Earth.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Stephanie Pappas is a contributing writer for Live Science, covering topics ranging from geoscience to archaeology to the human brain and behavior. She was previously a senior writer for Live Science but is now a freelancer based in Denver, Colorado, and regularly contributes to Scientific American and The Monitor, the monthly magazine of the American Psychological Association. Stephanie received a bachelor's degree in psychology from the University of South Carolina and a graduate certificate in science communication from the University of California, Santa Cruz.