Gut Bacteria Build Weapons from Viruses

Bacteria in the gut can unexpectedly manufacture viruses to kill off rivals during intestinal shootouts of sorts, researchers have found.

These findings could help lead to new ways to kill off dangerous germs, scientists added.

The average human gut is home to trillions of bacteria that outnumber human cells in the body by a factor of 10 to 1. Often these bacteria are helpful, aiding in digestion and synthesis of key vitamins.

Many bacteria in the digestive tract are infected with and churn out viruses known as bacteriophages, or phages for short. Bacteriophages only target and destroy bacteria — researchers have investigated them for nearly a century as an alternate way to fight bacterial infections.

"The gut microbiota harbors a teeming universe of phages," researcher Lora Hooper, a microbiologist at the University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center in Dallas, told LiveScience. "However, nothing was known about whether these phages were benefiting their bacterial hosts, whether they were predators, or anything about their role in the larger context of the gut ecosystem." [Tiny & Nasty: Images of Things That Make Us Sick]

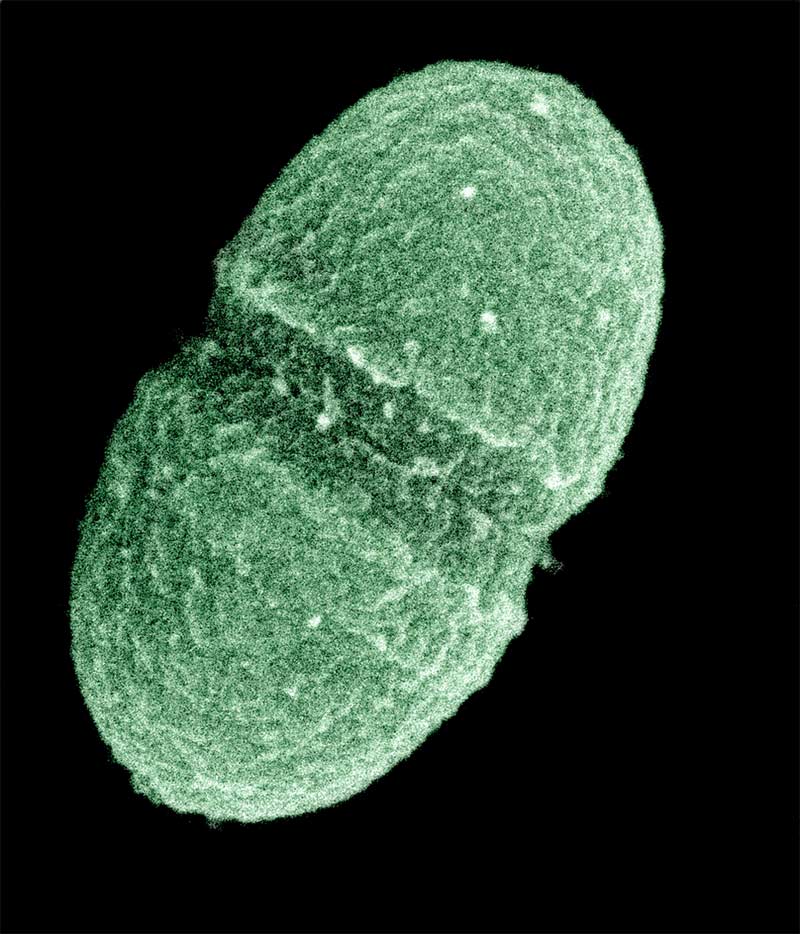

Scientists focused on Enterococcus faecalis, a gut microbe that can makes up nearly 1 percent of all bacteria in the digestive tract and is a leading cause of antibiotic-resistant hospital-acquired bacterial infections of the blood. Genetic analysis of this species has revealed it comes in a highly diverse range of strains.

Phages have woven their genomes directly into that of E. faecalis. It takes extra energy for the bacterium to manufacture these viruses, "suggesting that harboring the phage must confer a significant advantage to the host bacteria," Hooper said. "Otherwise we would not expect the host bacteria to maintain the phage genomes."

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Researcher Breck Duerkop noticed that E. faecalis started producing more phages when he introduced it into otherwise germ-free mice and let it grow in their intestines. "He was curious about why this would be, and his curiosity led to the findings," Hooper said.

The scientists discovered that one strain of E. faecalis named V583 could generate phages that killed contending strains in live mice.

"This phage confers benefit to its E. faecalis host by acting as a weapon against other E. faecalis strains that are competing for nutrients in the same intestinal niche," Hooper said.

Intriguingly, the phage weapon that a strain called V583 produces is stitched together from two different phages — one gives structure to the composite, while the other helps it infect victims.

"This is one of the first examples of intraspecies bacterial warfare in the intestinal ecosystem," Hooper added. "Like many discoveries in science, this one was a complete accident."

The researchers suspect the precursors of this phage colonized V583 but failed to kill it. V583 then manufactured the phage, using it to kill its rivals, which led both V583 and the phage to flourish.

"One interesting question is whether there are other examples of intraspecies shootouts going on in the intestine," Hooper said. "We plan to look for bacteriophage in other bacterial species that perform a similar function in defending the intestinal niche of their host bacteria."

This research suggests that bacteriophages might eventually be used to kill off dangerous intestinal germs, "or otherwise might be used to shape the intestinal bacterial community in a way that is more beneficial for humans," Hooper said.

The scientists detailed their findings online today (Oct. 8) in the journal Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.