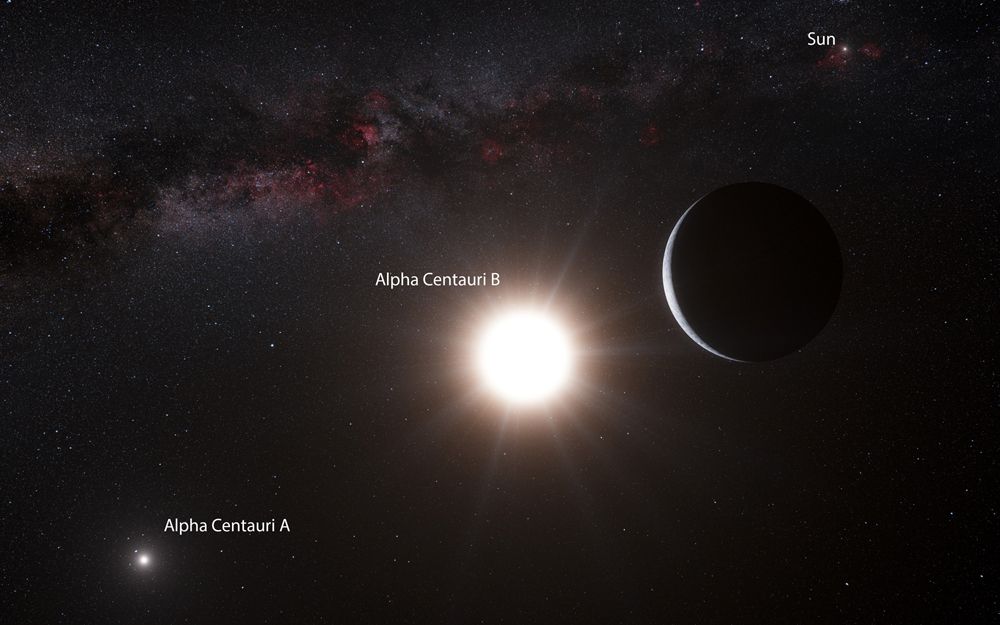

The star system closest to our own sun hosts a planet with roughly Earth's mass and may harbor other alien worlds as well, a new study reports.

Astronomers detected the alien planet around the sunlike star Alpha Centauri B, which is part of a three-star system just 4.3 light-years away from us. The newfound world is about as massive as Earth, but it's no Earth twin; its heat-blasted surface may be covered with molten rock, researchers said.

The mere existence of the planet, known as Alpha Centauri Bb, suggests that undiscovered worlds may lurk farther away from its star — perhaps in the habitable zone, that just-right range of distances where liquid water can exist.

"Most of the low-mass planets are in systems of two, three to six or seven planets, out to the habitable zone," study co-author Stephane Udry, of the Geneva Observatory, told reporters today (Oct. 16).

So the discovery "opens really good prospects for detecting planets in the habitable zone in a system that is very close to us," Udry added. "In that sense, this system is a landmark."

Alpha Centauri Bb zips around its star every 3.2 days, orbiting at a distance of just 3.6 million miles (6 million kilometers). For comparison, Earth orbits about 93 million miles, or 150 million km, from the sun. [Gallery: Nearby Alien Planet Alpha Centauri Bb]

A difficult detection

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

The research team, led by Xavier Dumusque of Geneva Observatory and the University of Porto in Portugal, spotted Alpha Centauri Bb using an instrument called the High Accuracy Radial velocity Planet Searcher, or HARPS.

HARPS is part of the European Southern Observatory's 11.8-foot (3.6 meters) telescope at the La Silla Observatory in Chile. The instrument allows astronomers to pick up the tiny gravitational wobbles an orbiting planet induces in its parent star.

In the case of Alpha Centauri Bb, these wobbles are very tiny indeed; the planet causes its star to move back and forth at no more than 1.1 mph (1.8 kph). It took more than 450 HARPS measurements spread out over four years of observing to detect the planet's signal, Dumusque said.

"It’s an extraordinary discovery, and it has pushed our technique to the limit," he said in a statement.

The detection, to be published tomorrow (Oct. 17) in the journal Nature, was so difficult that some astronomers aren't yet convinced that Alpha Centauri Bb exists.

For example, Artie Hatzes of the Thuringian State Observatory in Germany lauded the discoverers' technical achievement but said he believes the jury is still out.

"As the American astronomer Carl Sagan once said, 'Extraordinary claims require extraordinary evidence,'" Hatzes wrote in a commentary piece in the same issue of Nature. "Although a planetlike signal is present in the data, the discovery does not quite provide the 'extraordinary evidence.' It is a weak signal in the presence of a larger, more complicated signal. In my opinion, the matter is still open to debate."

Udry, however, said that the team's statistical analyses show a "false alarm probability" of just one in 1,000 — meaning there's a 99.9 percent chance that the planet exists.

And some experts don't agree with Hatzes that Alpha Centauri Bb requires extraordinary supporting evidence.

"The reason why this seems to be an extraordinary claim is because everyone has heard of Alpha Centauri B; it's a household name," said Greg Laughlin of the University of California, Santa Cruz, who was not part of the discovery team. "It's extraordinary not so much in terms of the robustness of the result, but rather just in terms of the fact that it's a well-known nearby star."

Mysterious flying objects, and other unexplainable skylights, have long enticed the human imagination, from Roswell rumors to alien conspiracies on The X-Files. Have you ever seen a UFO? Do you believe the truth is out there?

UFO Quiz: What's Really Out There

A lava world?

Dumusque and his colleagues determined that Alpha Centauri Bb is about 13 percent more massive than Earth, suggesting it's a rocky world. In addition to being the closest known exoplanet, it's also the first planet with a mass similar to Earth ever found around a sunlike star, researchers said. [Gallery: The Smallest Alien Planets]

Alpha Centauri Bb's extreme closeness to its parent star probably gives the planet a surface temperature around 2,240 degrees Fahrenheit (1,227 degrees Celsius), making it unsuitable for life, researchers said.

"At this temperature, there is a lot of chance that the surface — if it's made of rock, for example — it's not solid, but it's more like lava," Dumusque told reporters today.

Even though it resides in a three-star system — consisting of close-orbiting Alpha Centauri A and Alpha Centauri B, along with the more distant Proxima Centauri — the newfound world's orbit is stable over the long haul, Laughlin said. So are orbits in Alpha Centauri B's habitable zone, he added.

It's possible that Alpha Centauri A and Proxima Centauri may host planets as well, Udry said. The system will likely be the subject of newly intense scientific scrutiny, as astronomers seek to confirm the existence of Alpha Centauri Bb, learn more about it (such as whether or not it has an atmosphere) and hunt for additional nearby alien worlds.

"If you want to envision exploring this system, then it's almost twice as easy to get there as anywhere else," Laughlin said. "This is our backyard, and to find out that planet formation did occur there is just extraordinarily exciting."

Astronomers have now discovered more than 800 exoplanets, but thousands more — including 2,300 detected by NASA's planet-hunting Kepler Space Telescope to date — await confirmation by follow-up investigations. Work so far suggests that small, rocky planets such as Earth are quite common throughout our Milky Way galaxy.

This story was provided by SPACE.com, a sister site to LiveScience. Follow SPACE.com senior writer Mike Wall on Twitter @michaeldwall or SPACE.com @Spacedotcom. We're also on Facebook and Google+.