How T. Rex Ate Triceratops in 4 Easy Steps

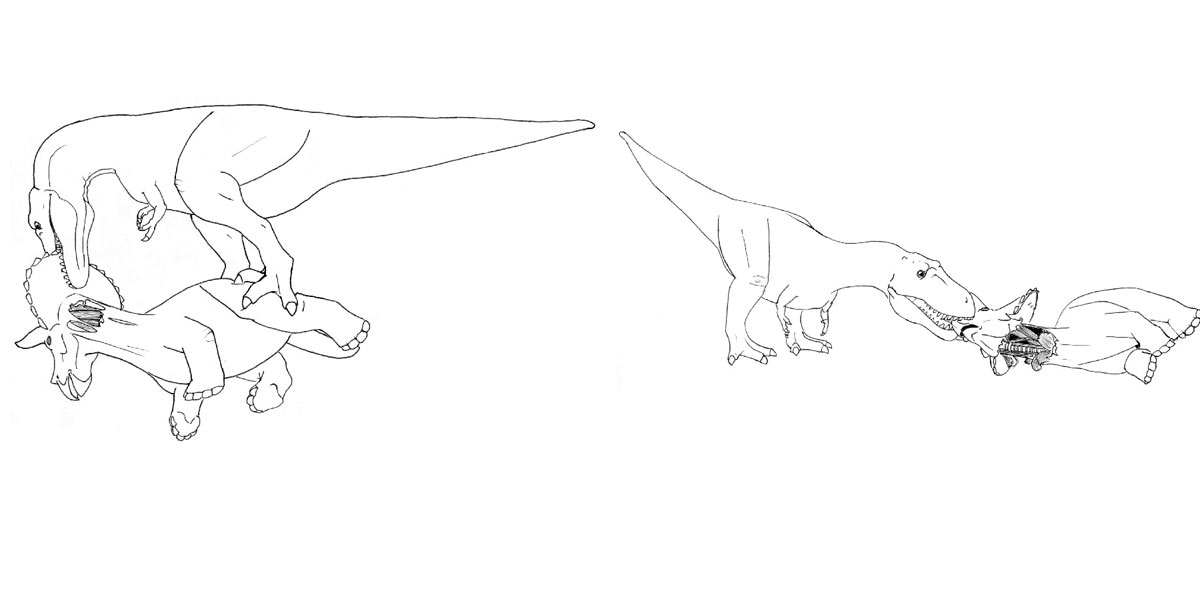

Step 1: Get a good grip on the bony frill. Step 2: Rip off the head. Step 3: Nibble on the face. Step 4: Savor the delicate cuts at the neck.

This is how researchers say a Tyrannosaurus may have feasted on a Triceratops during the age of the dinosaurs.

A team of scientists led by paleontologist Denver Fowler from the Museum of the Rockies examined 18 Triceratops fossil specimens, mostly skulls, from Montana's Hell Creek Formation. All of the fossil bones had evidence of Tyrannosaurus tooth marks.

Scientists have found isolated remains of Tyrannosaurus tooth marks on Triceratops fossils before, but Fowler's study has lots of specimens from the same region.

"Plus, they're tooth marks on skull bones which is a bit weird since we typically think of the body being the major source of nutrients for a carnivore," he wrote in an email to LiveScience.

His team found extensive puncture and pull marks on the frills of many specimens. As this bony armor around the neck of the Triceratops would not have been a good source of meat, the markings suggest the Tyrannosaurus was gripping the frill in its mouth to rip off the Triceratops head to get at its nutrient-rich neck muscles, the researchers said.

Other bone markings suggest the meal was not just a violent, flesh-ripping affair. Precise bites along the front of several Triceratops skulls indicate the Tyrannosaurus carefully nibbled on the tender meat of the face.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

None of the bones showed signs of healing, which told the scientists that the biting took place after the Triceratops had died. As Fowler told LiveScience, "It's actually really tough to show that two animals were belligerents in life."

Fowler presented his preliminary findings last week in Raleigh, N.C., at the Society of Vertebrate Paleontology's annual meeting. His research is ongoing and has not yet been published in a peer-reviewed scientific journal. "Taking the story deeper than the gory surface, with the final paper we're hoping to be able to say more about ecological interactions," such as changes in feeding patterns, he said.

The findings raise questions about how the feeding behavior of Tyrannosaurus changed throughout its life span. While adults would have been able to tear apart a tough Triceratops with their thick teeth, the team believes younger ones may have had to turn to different feeding strategies to avoid tooth damage.

Follow LiveScience on Twitter @livescience. We're also on Facebook & Google+.