Weather or Climate: What Caused Hurricane Sandy?

An unusual trio of weather factors conspired to create Hurricane Sandy, the enormous storm churning toward the mid-Atlantic states today — that much is clear. What researchers aren't as sure of is how much climate change influenced this particular storm.

Attributing a certain event to climate change is always tricky territory, so much so that some scientists contacted by LiveScience said it was too early to make any judgments. Others were more willing to say that global warming contributed to, but did not cause, the massive Category 1 storm.

"The climate influences on this are what we might call the 'new normal,' the changed environment this storm is operating in," Kevin Trenberth, who heads the climate analysis section of the National Center for Atmospheric Research, told LiveScience.

Sandy's cause

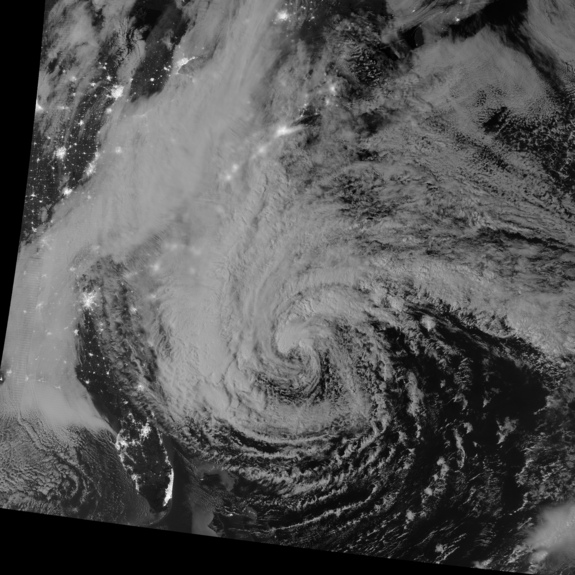

In the immediate term, three factors have come together to make Hurricane Sandy what it is: A huge storm with winds gusting up to 90 mph (145 kph) set to make landfall somewhere on the East Coast Monday night. First, hurricane season is still on, meaning the tropics are still actively generating storms. That's Sandy's origin. [Photos: Hurricane Sandy From Space]

But a storm like Sandy would normally be losing steam by now as it moved into colder, less energetic waters, said David Robinson, a Rutgers University professor and New Jersey's state climatologist. In this case, however, a trough of low pressure dipping down from the Arctic is feeding the hurricane, actually strengthening its intensity as it moves northward. (Higher tides because of a full moon may also increase flooding from the storm.)

Those conditions are the same as 1991's "Perfect Storm," a tempest that occurred when a nor'easter fed by Arctic air absorbed Hurricane Grace. But that storm never made landfall. The third weather factor feeding Sandy, a high-pressure system, is pushing the hurricane onshore, making this "about the worst case imaginable," Robinson said.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

That block of high pressure in the northeastern Atlantic Ocean is shunting Sandy toward land like a peg in a pinball machine.

"You've got three factors here that have come together in just the right pattern to create a storm of this type," Robinson told LiveScience. "That's why it's very rare."

Climate change and Hurricane Sandy

The more complex question is whether global warming has played a supporting role in the storm's strength. Trenberth said there is reason to think that climate change could be making Sandy wetter and stronger.

Hurricanes and tropical cyclones are fueled by warm water evaporating into the air. Ocean surface temperatures are up 0.9 degrees Fahrenheit (0.5 degrees Celsius) from about a century ago, a fact that may boost storm intensity. A recent study released in September in the journal Geophysical Research Letters, for example, found that hurricanes and tropical cyclones ramp up faster than they did 25 years ago. Globally, these storms reach Category 3 status, with winds up to 129 mph (208 kph), nine hours earlier on average than they used to, the study found.

With warmer ocean surfaces comes warmer air above the oceans, Trenberth said. With warmer temperatures, this ocean air now holds about 4 percent more moisture than it did in the 1970s.

"In general, we estimate it increases the risk that the intensity of hurricanes can be somewhat greater and particularly the rainfall from hurricanes is about 5 to 10 percent greater than it otherwise would be," Trenberth said. [Video: Hurricane Sandy's Intensity]

In the case of 2005's Hurricane Katrina, which dumped at least 10 inches (25 centimeters) of rain along its track on the Gulf Coast, that means about 1 inch was attributable to climate change, Trenberth said. Sandy could dump similar levels of moisture over the Northeast.

Trenberth added that "there are signs" that storms of Category 3 and above are becoming more common, but warned that hurricanes show tremendous natural variability from year to year, driven largely by climate patterns set up by El Niño.

That sort of variability made Robinson wary of attributing any of Sandy's destructive power to climate change.

"I told myself when I got up this morning, 'I'm not going to talk about climate change,'" Robinson said. "You can't take one rogue event like this and start ascribing anything but the current three phasing conditions that are leading to it."

Robinson didn't rule out that storms may get worse in a warming world, however.

"I wish I was going to be around 50 years from now sitting here in this position, because we might be able to say that with the warming of the atmosphere and the greater energy of it, we can reel off these superstorms more frequently," he said. "To say that this one is associated with that would really be doing a disservice to the science."

Follow Stephanie Pappas on Twitter @sipappas or LiveScience @livescience. We're also on Facebook & Google+.

Stephanie Pappas is a contributing writer for Live Science, covering topics ranging from geoscience to archaeology to the human brain and behavior. She was previously a senior writer for Live Science but is now a freelancer based in Denver, Colorado, and regularly contributes to Scientific American and The Monitor, the monthly magazine of the American Psychological Association. Stephanie received a bachelor's degree in psychology from the University of South Carolina and a graduate certificate in science communication from the University of California, Santa Cruz.