SAN FRANCISCO — Ötzi the Iceman, an astonishingly well-preserved Neolithic mummy found in the Italian Alps in 1991, was a native of Central Europe, not a first-generation émigré from Sardinia, new research shows. And genetically, he looked a lot like other Stone Age farmers throughout Europe.

The new findings, reported Thursday (Nov. 8) here at the American Society of Human Genetics conference, support the theory that farmers, and not just the technology of farming, spread during prehistoric times from the Middle East all the way to Finland.

"The idea is that the spread of farming and agriculture, right now we have good evidence that it was also associated with a movement of people and not only technology," said study co-author Martin Sikora, a geneticist at Stanford University.

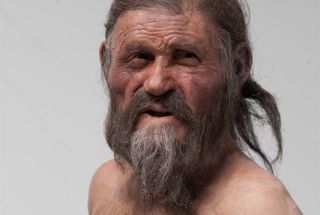

In what may be the world's oldest cold case, Ötzi was pierced by an arrow and bled to death on a glacier in the Alps between Austria and Italy more than 5,000 years ago. [Album: A New Face for Otzi the Iceman]

Scientists sequenced Ötzi's genome earlier this year, yielding a surprising result: The Iceman was more closely related to present-day Sardinians than he was to present-day Central Europeans.

But the researchers sequenced only part of the genome, and the results didn't resolve an underlying question: Did most of the Neolithic people in Central Europe have genetic profiles more characteristic of Sardinia, or had Ötzi's family recently emigrated from Southern Europe?

"Maybe Ötzi was just a tourist, maybe his parents were Sardinian and he decided to move to the Alps," Sikora said.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

That would have required Ötzi's family to travel hundreds of miles, an unlikely prospect, Sikora said.

"Five thousand years ago, it's not really expected that our populations were so mobile," Sikora told LiveScience.

To answer that question, Sikora's team sequenced Ötzi's entire genome and compared it with those from hundreds of modern-day Europeans, as well as the genomes of a Stone Age hunter-gatherer found in Sweden, a farmer from Sweden, a 7,000-year-old hunter-gatherer iceman found in Iberia, and an Iron Age man found in Bulgaria.

The team confirmed that, of modern people, Sardinians are Ötzi's closest relatives. But among the prehistoric quartet, Ötzi most closely resembled the farmers found in Bulgaria and Sweden, while the Swedish and Iberian hunter-gatherers looked more like present-day Northern Europeans.

The findings support the notion that people migrating from the Middle East all the way to Northern Europe brought agriculture with them and mixed with the native hunter-gatherers, enabling the population to explode, Sikora said.

While the traces of these ancient migrations are largely lost in most of Europe, Sardinian islanders remained more isolated and therefore retain larger genetic traces of those first Neolithic farmers, Sikora said.

The findings add to a growing body of evidence showing that farming played a major role in shaping the people of Europe, said Chris Gignoux, a geneticist at the University of California San Francisco, who was not involved in the study.

"I think it's really intriguing," Gignoux said. "The more that people are sequencing these ancient genomes from Europe, that we're really starting to see the impact of farmers moving into Europe."

Follow LiveScience on Twitter @livescience. We're also on Facebook & Google+.

Tia is the managing editor and was previously a senior writer for Live Science. Her work has appeared in Scientific American, Wired.com and other outlets. She holds a master's degree in bioengineering from the University of Washington, a graduate certificate in science writing from UC Santa Cruz and a bachelor's degree in mechanical engineering from the University of Texas at Austin. Tia was part of a team at the Milwaukee Journal Sentinel that published the Empty Cradles series on preterm births, which won multiple awards, including the 2012 Casey Medal for Meritorious Journalism.

Most Popular