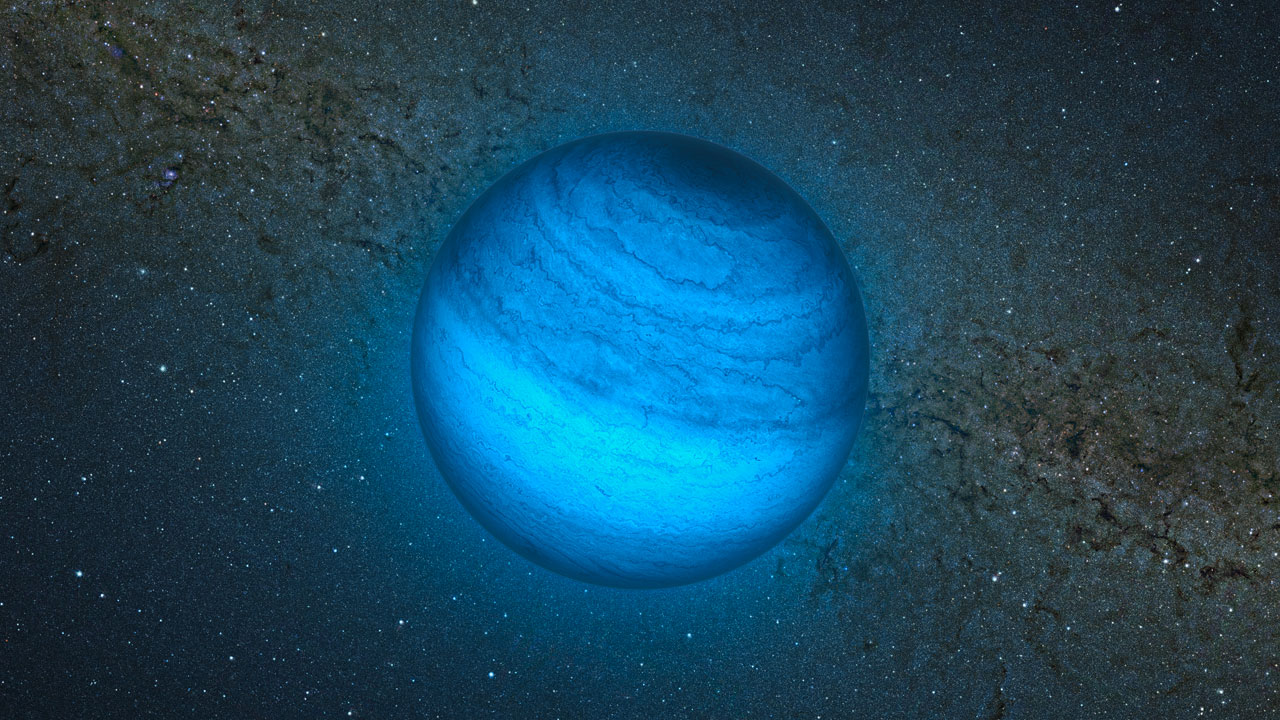

Astronomers have discovered a potential "rogue" alien planet wandering alone just 100 light-years from Earth, suggesting that such starless worlds may be extremely common across the galaxy.

The free-floating object, called CFBDSIR2149, is likely a gas giant planet four to seven times more massive than Jupiter, scientists say in a new study unveiled today (Nov. 14). The planet cruises unbound through space relatively close to Earth (in astronomical terms; the Milky Way galaxy is 100,000 light-years wide), perhaps after being booted from its own solar system.

"If this little object is a planet that has been ejected from its native system, it conjures up the striking image of orphaned worlds, drifting in the emptiness of space," study leader Philippe Delorme, of the Institute of Planetology and Astrophysics of Grenoble in France, said in a statement.

Orphan planet, or something else?

Delorme and his team detected CFBDSIR2149's infrared signature using the Canada-France-Hawaii Telescope, then examined the body's properties with the European Southern Observatory's Very Large Telescope in Chile. [Video: Rogue Planet Has No Parent Star]

The newfound object appears to be among a stream of young stars called the AB Doradus moving group, the closest such stream to our own solar system.

Scientists think the AB Doradus stars all formed together between 50 million and 120 million years ago. If CFBDSIR2149 is indeed associated with the group — and researchers cite a nearly 90 percent probability — then the object is similarly young.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

And if the discovery team is right about CFBDSIR2149's age, the body is likely a planet, with an average temperature of 806 degrees Fahrenheit (430 degrees Celsius), researchers said.

There's still a slight chance that CFBDSIR2149 is a brown dwarf — a strange object that's larger than a planet but too small to trigger the internal nuclear fusion reactions required to become a full-fledged star. Additional observations should help decide the matter.

"We need new observations to confirm that this object belongs to the AB Doradus moving group," Delorme told SPACE.com via email. "With a good distance measurement and a more accurate proper motion, we will be able to increase (or decrease) the probability that it is indeed a planet."

The new study was published today in the journal Astronomy & Astrophysics.

Billions of starless planets?

The discovery of a starless alien planet would not be shocking, at least not anymore. In the last year or so, astronomers have spotted a number of such orphan worlds — so many, in fact, that some scientists think parentless planets are the rule rather than the exception.

One 2011 study, for example, estimated that rogue worlds outnumber "normal" planets with obvious host stars by at least 50 percent throughout the Milky Way. If that's the case, the galaxy that includes Earth probably also hosts billions of orphan planets.

And gas giants may be in the minority among these solitary wanderers, researchers say.

"We now know that such massive planets are rare and that Neptunes or Earth-mass planets are much more common," Delorme said. "We also know that massive objects are more difficult to eject [from solar systems] than light ones. If you follow the rationale, you deduce that ejected exo-Neptunes and ejected exo-Earths should be much more common than objects like CFBDSIR2149."

It's exciting to have a starless planet so close to Earth, researchers say. Future telescopes should be able to learn a great deal about CFBDSIR2149, since they won't have to contend with the overwhelming glare of a nearby host star.

"This object is a really easy-to-study prototype of the 'normal' giant planets we hope to discover and study with the upcoming generation of direct-imaging instruments," Delorme said. "It will help to improve our forecast of these objects' luminosity and hence help us discover them ―and, once discovered, it will help us understand the physics of their atmospheres."

This story was provided by SPACE.com, a sister site to Live Science. Follow SPACE.com senior writer Mike Wall on Twitter @michaeldwall or SPACE.com @Spacedotcom. We're also on Facebook and Google+.