How a Medium's Brain Changes in a Trance

The supernatural experience of having the dead communicate through the living has now been analyzed with brain scans.

Their brain activity suggests those more expert at entering these otherworldly trances often experienced a drop in focus, self-awareness and consciousness, scientists said.

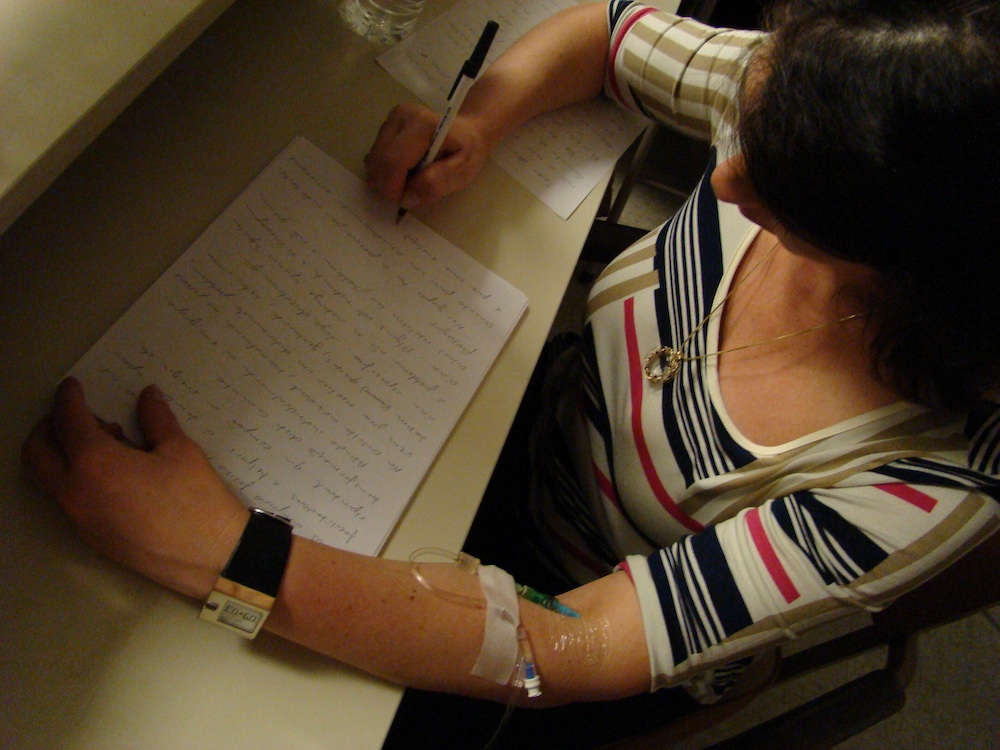

In the practice known as mediumship, people known as mediums claim to be in touch with or even under the control of the spirits of the dead. One form of mediumship, known as psychography, involves trances where the dead allegedly write using the hands of the living medium.

"Spiritual experiences affect cerebral activity, this is known. But the cerebral response to mediumship, the practice of supposedly being in communication with, or under the control of the spirit of a deceased person, has received little scientific attention," said researcher Andrew Newberg, director of research at the Myrna Brind Center of Integrative Medicine at Thomas Jefferson University in Philadelphia.

"This study grows out of a larger approach we have to try and understand religious and spiritual experiences and the human brain, and how they're related to one another, a growing field we call 'neurotheology,'" Newberg said. [The Science of Death: 10 Tales from the Crypt]

Trance writing

To learn more about psychography, scientists analyzed 10 Brazilian mediums — five who were experienced and five who were less expert. They were injected with a radioactive tracer that allowed researchers to study blood flow in their brains, seeing which regions were active and inactive during normal writing and psychography. For the trance writing, volunteers were asked to follow their usual methods for "contacting the dead" and writing while in this trance state, while during normal writing they were asked to write about a topic they often wrote on during psychography.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

"I don't think this study proves or disproves whether what they're claiming to be doing is what they're doing," Newberg said. "This study shows us what happens when mediums engage in this practice. An atheist may conclude the brain is just creating the experience, while mediums might say that when their brain becomes receptive to the spirits, this is what happens — both conclusions are at least consistent with the findings."

The mediums had anywhere from 15 to 47 years of psychography experience, performing up to 18 psychographies per month for free. All were right-handed, were in good mental health, and not currently using any psychiatric drugs.

Experienced psychographers often reported out-of-body experiences and little or no awareness of what they were writing. Less expert psychographers often reported feeling inspired and writing phrases dictated to them in their minds. The psychographic writing generated during the study involved topics such as the need to respect one another, the breaking of vicious cycles that lead to greed and spiritual ignorance, the cultivation of virtue and character even in difficult times, the necessity of seeing through hypocrisy and lies, and the importance of building bridges between spirituality and science.

When the scientists analyzed the writing psychographers created, they found that psychographic writing was more complex compared with normal writing — for instance, words were longer, more words were used per sentence, and psychographic writers deployed more descriptive words than when they were in a non-trance state. This increase in complexity was especially seen in the psychographies of the expert mediums.

Trance brain activity

Intriguingly, experienced psychographers showed lower levels of activity in the brain's frontal lobe regions of the left anterior cingulate and right precentral gyrus during psychography. These areas are linked with reasoning, planning, generating language, movement and problem solving, perhaps reflecting an absence of focus, self-awareness and consciousness during psychography. These psychographers also experienced less activity in the left hippocampus, which is linked with emotion, and the right superior temporal gyrus, which is linked with hearing.

"It's very interesting — we typically think of the brain being very active when a person is doing a particular task, but here we find the opposite," Newberg told LiveScience.

Less expert psychographers showed just the opposite brain behaviors, such as significantly increased levels of blood flow in the same areas during psychography. This increased activity may be related to how they apparently had to "work harder" during psychography, researchers said. [The 10 Greatest Mysteries of the Mind]

"A good analogy to what might be going on is how expert pianists differ from novices," Newberg said. "When you're learning how to play the piano, you have to concentrate on where your fingers go, think about what note is played next, but when you become a concert pianist, your hand flows over the keyboard — you almost don't have to think about what you're doing. It makes sense that the brain would become less active as it becomes more efficient at doing something."

The fact that the psychographers were not mentally ill suggests these unusual experiences might be common in the general population and not necessarily related to mental disorders. The researchers suggest that as frontal lobe activity decreased, the brain's creativity-related areas become less inhibited, similar to what happens when alcohol or drugs are taken.

"Likewise, meditation and musical improvisation might be associated with lower levels of brain activity, which may favor relaxation and creativity," researcher Julio Peres, a clinical psychologist and neuroscientist at the University of Sao Paulo in Brazil, told LiveScience. However, alcohol, drug use, meditation and musical improvisation all lead to brain activity quite distinct from psychography, researchers noted.

"This first-ever neuroscientific evaluation of mediumistic trance states reveals some exciting data to improve our understanding of the mind and its relationship with the brain," Newberg said. "These findings deserve further investigation."

The scientists detailed their findings online Nov. 16 in the journal PLoS ONE.

Follow LiveScience on Twitter @livescience. We're also on Facebook & Google+.