SAN FRANCISCO — Volcanic activity in modern-day India, not an asteroid, may have killed the dinosaurs, according to a new study.

Tens of thousands of years of lava flow from the Deccan Traps, a volcanic region near Mumbai in present-day India, may have spewed poisonous levels of sulfur and carbon dioxide into the atmosphere and caused the mass extinction through the resulting global warming and ocean acidification, the research suggests.

The findings, presented Wednesday (Dec. 5) here at the annual meeting of the American Geophysical Union, are the latest volley in an ongoing debate over whether an asteroid or volcanism killed off the dinosaurs about 65 million years ago in the mass die-off known as the K-T extinction.

"Our new information calls for a reassessment of what really caused the K-T mass extinction," said Gerta Keller, a geologist at Princeton University who conducted the study.

For several years, Keller has argued that volcanic activity killed the dinosaurs.

But proponents of the Alvarez hypothesis argue that a giant meteorite impact at Chicxulub, Mexico, around 65 million years ago released toxic amounts of dust and gas into the atmosphere, blocking out the sun to cause widespread cooling, choking the dinosaurs and poisoning sea life. The meteorite may impact may also have set off volcanic activity, earthquakes and tsunamis. [Wipe Out: History's Most Mysterious Extinctions]

The new research "really demonstrates that we have Deccan Traps just before the mass extinction, and that may contribute partially or totally to the mass extinction," said Eric Font, a geologist at the University of Lisbon in Portugal, who was not involved in the research.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Sea cockroach

In 2009, oil companies drilling off the Eastern coast of India uncovered eons-old lava-filled sediments buried nearly 2 miles (3.3 kilometers) below the ocean surface.

Keller and her team got permission to analyze the sediments, finding they contained plentiful fossils from around the boundary between the Cretaceous-Tertiary periods, or K-T Boundary, when dinosaurs vanished.

The sediments bore layers of lava that had traveled nearly 1,000 miles (1,603 km) from the Deccan Traps. Today, the volcanic region spans an area as big as France, but was nearly the area of Europe when it was active during the late Cretaceous period, said Adatte Thierry, a geologist from the University of Lausanne in France who collaborated with Keller on the research.

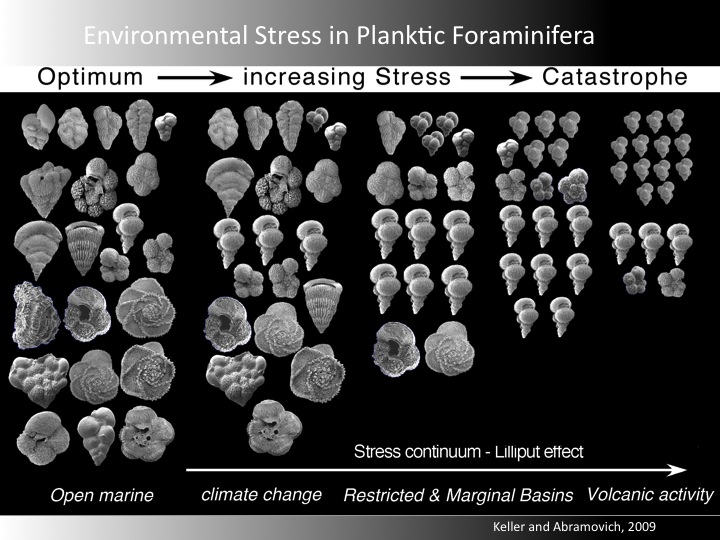

Within the fossil record, plankton species got fewer, smaller and maintained less elaborate shells immediately after lava layers, which would indicate it happened in years after the eruptions. Most species gradually died off. In their wake, a hardy plankton genus with a small, nondescript exoskeleton, called Guembilitria, exploded within the fossil record. Keller's team found similar trends in their analysis of marine sediments from Egypt, Israel, Spain, Italy and Texas. While Guembilitria species represented between 80 percent and 98 percent of the fossils, other species disappeared.

"We call it a disaster opportunist," Keller told LiveScience. "It's like a cockroach — whenever things go bad, it will be the one that survives and thrives."

Guembilitria may have come to dominance worldwide when the huge amounts of sulfur (in the form of acid rain) released by the Deccan Traps fell into the oceans. There, it would've chemically binded with calcium, making that calcium unavailable to sea creatures that needed the element to build their shells and skeletons.

Around the same time in India, fossil evidence of land animals and plants vanished, suggesting the volcanoes caused mass extinctions on both land and in the sea there.

Global impact

In past work, the team has also found evidence at Chicxulub that casts doubt on the notion of a meteorite causing the extinction.

Sediments containing iridium, the chemical signature of an asteroid, show up after the extinction occurred, contradicting the notion that it could have caused a sudden die-off, Keller said.

A meteorite impact also would not have produced enough toxic sulfur and carbon dioxide to match the levels seen in the rocks, so it may have worsened the mass extinction, but couldn't have caused it, she said.

"The meteorite is just too small to cause the extinction."

Follow LiveScience on Twitter @livescience. We're also on Facebook & Google+.

Tia is the managing editor and was previously a senior writer for Live Science. Her work has appeared in Scientific American, Wired.com and other outlets. She holds a master's degree in bioengineering from the University of Washington, a graduate certificate in science writing from UC Santa Cruz and a bachelor's degree in mechanical engineering from the University of Texas at Austin. Tia was part of a team at the Milwaukee Journal Sentinel that published the Empty Cradles series on preterm births, which won multiple awards, including the 2012 Casey Medal for Meritorious Journalism.