The fearsome box jellyfish packs venom that is among the deadliest in the world, but a new treatment may take the sting out of its powerful poison, according to a new study.

The study researchers found that a zinc-based compound prevented death in mice injected with box-jellyfish venom. The compound — zinc gluconate, a nutritional supplement — seems to work by preventing certain ions (charged particles) that keep the heart beating from leaking out of blood vessels.

If follow-up studies confirm the benefits in larger animals, the compound could one day be used to prevent people from dying of jellyfish stings. Anecdotal evidence looks promising: A topical version of the compound was used to reduce the pain and swelling of a jellyfish sting received by Diana Nyad in August during her attempt to swim the 103 miles (166 kilometers) between Florida and Cuba.

Deadly venom

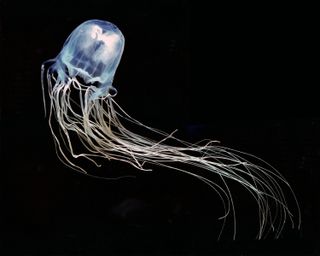

Snakes, insects, fish and even lizards use venom to defend themselves or take down prey, but the sting of the Australian box jellyfish (Chironex fleckeri) may be the most deadly: A single creature carries enough venom in its tentacles to kill 60 people.

"These are the most venomous animals in the world based upon fatalities over the last 30 years," said study author Angel Yanagihara, a biochemist at the University of Hawaii at Manoa.

Box jellyfish float in the waters from Australia all the way to Vietnam. The ethereal creatures can sport 6.5-foot (2-meter)-long, ribbonlike tentacles that often attach to swimmers or scuba divers and inject venom through hundreds of thousands of microscopic, harpoonlike barbs, Yanagihara said. [Gallery: Amazing Photos of Jellyfish]

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

"All that venom then seeps into the bloodstream. With each beat of your heart it's being pumped around your circulatory system," she said.

The deadly stings can kill quickly by causing cardiac arrest. Until now, doctors had no effective treatments to counteract the venom. Instead, they would treat a cascade of symptoms, such as high or low blood pressure, and hope for the best, she said.

"It's usually a race against time where the clinician is treating symptoms as they crop up," Yanagihara told LiveScience.

Leaky cells

Past work had shown the venom contained a chemical that creates ringlike structures that attach to blood vessels, creating tiny holes in them and making them leaky; exactly what was leaking out remained a mystery.

To find out, Yanagihara and her colleagues drew blood from humans, sheep, rats and mice, and mixed the samples with the jellyfish venom. The scientists then used electrical measurements to track the chemicals seeping out of the cells.

The team found that potassium ions were oozing out of red blood cells into plasma, the yellowish fluid in which blood cells float. The team concluded that a steep drop in potassium inside blood cells prevented heart muscle cells from beating properly. (The heart and other muscles require a difference in the levels of potassium inside and outside cells to generate force).

The pores also reminded Yanagihara of similar structures found in bacteria. By studying scientific experiments dating back as far as the 1880s, she found that scientists used zinc to prevent these bacterial pores from assembling. The similarity made her wonder whether zinc could be used to take the deadly sting out of box jellyfish venom.

To test that theory, the researchers gave two groups of mice venom injections, but one was administered a follow-up dose of zinc gluconate, a supplement routinely used to boost the zinc levels of premature babies. While all the mice injected just with jellyfish venom died within an hour, about half that also received the zinc treatment survived for the duration of the experiment.

The findings suggest that the zinc works by preventing blood cells from oozing potassium. If similar results are seen in follow-up studies, the supplement could be given as a treatment for unlucky people who encounter the deadly creatures while swimming or surfing.

Follow LiveScience on Twitter @livescience. We're also on Facebook & Google+.

Tia is the managing editor and was previously a senior writer for Live Science. Her work has appeared in Scientific American, Wired.com and other outlets. She holds a master's degree in bioengineering from the University of Washington, a graduate certificate in science writing from UC Santa Cruz and a bachelor's degree in mechanical engineering from the University of Texas at Austin. Tia was part of a team at the Milwaukee Journal Sentinel that published the Empty Cradles series on preterm births, which won multiple awards, including the 2012 Casey Medal for Meritorious Journalism.

Most Popular