Ancient Maya Predicted 1991 Solar Eclipse

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

LONG BEACH, Calif. — The Maya, best known these days for the doomsday they never foretold, may have accurately predicted astronomical phenomena centuries ahead of time, scientists find.

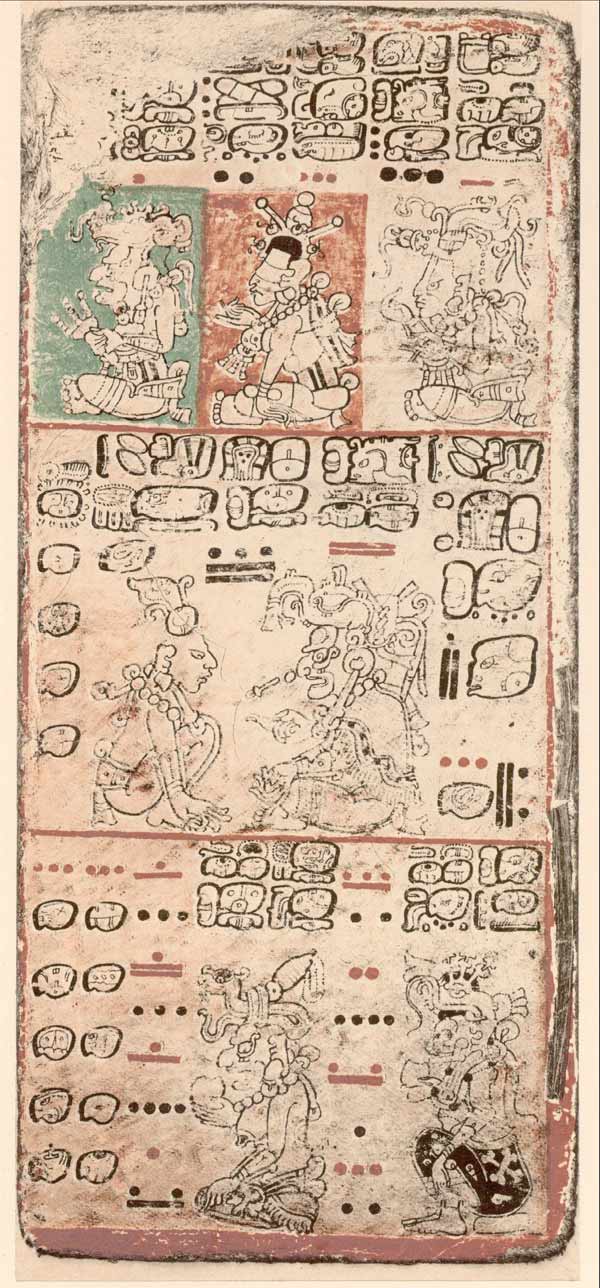

A new book, "Astronomy in the Maya Codices" (American Philosophical Society, 2011), which was awarded the Osterbrock Book Prize for historical astronomy here at the American Astronomical Society conference Monday (Jan. 7), details a series of impressive observations made by Mayan astronomers pre-16th century.

Anthropologist husband-wife team, Harvey and Victoria Bricker have devoted their lives to understanding the pre-Columbian Maya and how they understood the world around them. The Brickers conducted most of their work by translating complex hieroglyphics to see what Mayan scribes felt was most important to record on parchment.

By decoding early Mayan hieroglyphics from four different codices housed in Madrid, Paris, Mexico and Dresden, the Brickers tracked how the night sky would have looked to the Mayans when they were alive.

"We're dealing with real data," Harvey Bricker said. "They're not just squiggles."

The Brickers translated the dates cited in the Mayan calendar to correspond with our calendar and then used modern knowledge of planetary orbits and cycles to line up the Maya's data with ours. It was surprisingly accurate. [Image Gallery: Amazing Mayan Calendar Carvings]

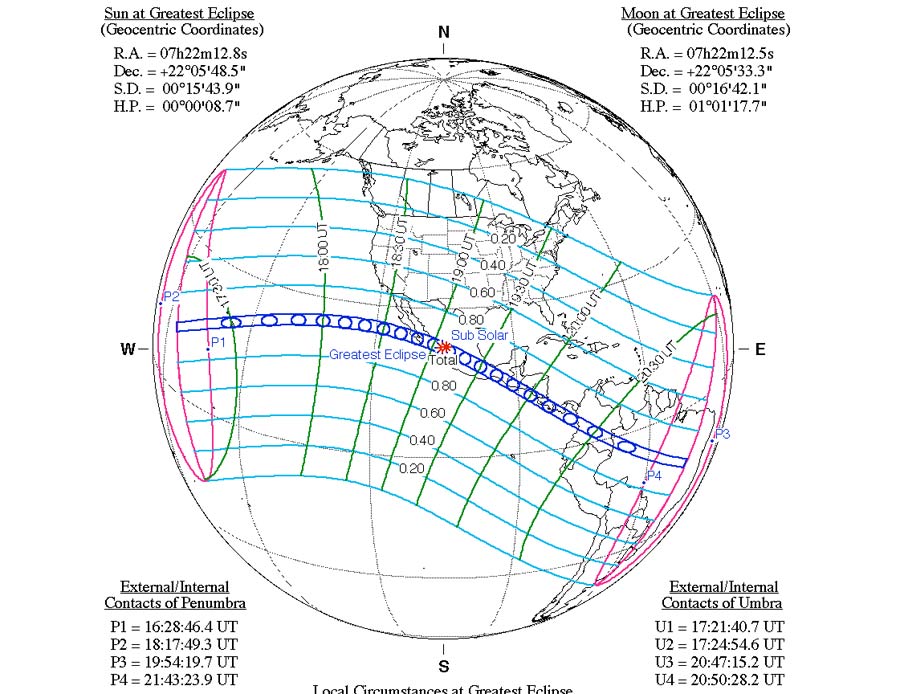

In fact, the Brickers found the astronomical calendar dated to the 11th or 12th century accurately predicted a solar eclipse to within a day in 1991, centuries after the Mayan civilization had ended. The 1991 eclipse occurred on July 11.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

The team also found that the Maya had a fair number of superstitions surrounding observable heavenly bodies in the night sky. On the friendly side, they had the sun and the moon — a god and goddess, respectively — whose cycles were easy to map, predict and keep track of. In the not-so-friendly camp were Venus and Mars. The motions of those two planets usually signaled doom and destruction depending upon their place in the sky, the Brickers found.

The manuscripts warned that if Venus shines upon children, old men and women or healthy young men at certain points in its orbit, then harm would come to them. Because the Maya wanted to make sure these potentially dangerous moments didn't interfere with the lives of their people, Harvey Bricker said, they kept extremely detailed records of where Venus and other planets appeared in the night sky on certain days.

Mars — an animalistic god — signified gloomy days to come for everybody.

"There was thought to be a relationship, and not a happy one, between phenomena associated with Mars and agriculture," Harvey Bricker said.

Follow Miriam Kramer on Twitter @mirikramer or LiveScience @livescience. We're also on Facebook & Google+.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus