Einstein Was Right: Space-Time Smooth, Not Foamy

Space-time is smooth rather than foamy, a new study suggests, scoring a possible victory for Einstein over some quantum theorists who came after him.

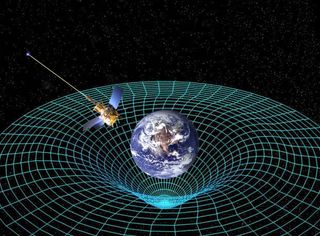

In his general theory of relativity, Einstein described space-time as fundamentally smooth, warping only under the strain of energy and matter. Some quantum-theory interpretations disagree, however, viewing space-time as being composed of a froth of minute particles that constantly pop into and out of existence.

It appears Albert Einstein may have been right yet again.

A team of researchers came to this conclusion after tracing the long journey three photons took through intergalactic space. The photons were blasted out by an intense explosion known as a gamma-ray burst about 7 billion light-years from Earth. They finally barreled into the detectors of NASA's Fermi Gamma-ray Space Telescope in May 2009, arriving just a millisecond apart.

Their dead-heat finish strongly supports the Einsteinian view of space-time, researchers said. The wavelengths of gamma-ray burst photons are so small that they should be able to interact with the even tinier "bubbles" in the quantum theorists' proposed space-time foam.

If this foam indeed exists, the three protons should have been knocked around a bit during their epic voyage. In such a scenario, the chances of all three reaching the Fermi telescope at virtually the same time are very low, researchers said.

So the new study is a strike against the foam's existence as currently imagined, though not a death blow.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

"If foaminess exists at all, we think it must be at a scale far smaller than the Planck length, indicating that other physics might be involved," study leader Robert Nemiroff, of Michigan Technological University, said in a statement. (The Planck length is an almost inconceivably short distance, about one trillionth of a trillionth the diameter of a hydrogen atom.)

"There is a possibility of a statistical fluke, or that space-time foam interacts with light differently than we imagined," added Nemiroff, who presented the results Wednesday (Jan. 9) at the 221st meeting of the American Astronomical Society in Long Beach, Calif.

If the study holds up, the implications are big, researchers said.

"If future gamma-ray bursts confirm this, we will have learned something very fundamental about our universe," Bradley Schaefer of Louisiana State University said in statement.

This story was provided by SPACE.com, a sister site to Live Science. Follow SPACE.com on Twitter @Spacedotcom. We're also on Facebook & Google+.

Most Popular