Elgin Marbles & the Parthenon

The Elgin Marbles, sometimes referred to as the Parthenon sculptures, are a collection of marble sculptures that originally adorned the top of the exterior of the Parthenon in Athens, Greece, and are now in London, England.

They are currently exhibited, free to the public, in the Duveen Gallery in the British Museum. Although today the sculptures appear white, originally they were painted in vivid colors, something that new research is revealing.

The marbles in London were removed from the Parthenon in the first decade of the 19th century under the auspices of Thomas Bruce, the seventh Earl of Elgin, and were first exhibited in London in 1807. Their removal is deeply controversial and the Greek government has requested that they be repatriated, a debate that has garnered extensive media attention. Not all the sculptures from the Parthenon are in the British Museum; another large portion is still in Athens, while a few other sculptures are in different museums throughout the world.

The Parthenon

A temple dedicated to the goddess Athena, the Parthenon is located on the Acropolis of ancient Athens. It is about 228 feet (69.5 meters) long by 101 feet (30.9 meters) wide and roughly 65 feet (20 meters) high. Construction of the temple started in 447 B.C., with work on its decorations continuing up to about 432 B.C., around the time war broke out with Sparta. At the time the Parthenon was created, Athens was at its height, the city’s vast navy helping it control an empire in the Aegean Sea.

There are three main types of sculptures on the exterior of the Parthenon that are now part of the Elgin Marbles.

Pediments

Pediments are large triangular shaped niches, which contained impressive sculptures, located high up on top of the Parthenon. One pediment is located on the east side of the building and another on the west. The sculptures on the east pediment tell the tale of the birth of the goddess Athena, while those on the west depict a battle between Athena and the god Poseidon to determine who would be the patron deity of Athens. The size of the sculptures varied depending on how close they were to the apex (the highest point) of the triangle.

The most impressive pediment sculptures that are part of the Elgin Marbles come from the east side and illustrate reactions to the birth of Athena.

According to myth, Athena was the daughter of Zeus and the goddess Metis. Zeus was afraid that Athena would become more powerful than him so he swallowed Metis whole while she was pregnant. This did not stop the pregnancy and Athena became so big that Zeus’ head was split open with an axe by the Greek blacksmith god Hephaestus, and the goddess was born.

Unfortunately, the sculptures depicting the head-blowing birth have not survived but the sculptures that are part of the Elgin Marbles do show the reactions of Greek deities to the birth. British Museum curator Ian Jenkins notes in his book "The Parthenon Sculptures" (Harvard University Press, 2007) that Athena was born “at daybreak” and sculptures show “the sun-god Helios and the heads of two of his four horses,” emerging from the floor of the pediment, rising “as if from the sea.”

Also observing the event is a nude image of Dionysus, god of wine and revelry, who is shown reclining and apparently enjoying a cup of wine, as if toasting the birth. To the right are two seated goddesses who, Jenkins says, are probably Demeter and her daughter Persephone, while further to the right is a heavily draped Greek girl, apparently a mortal human, who has taken flight after viewing the event.

Three goddess sculptures taken by Elgin would have been positioned to the right of the lost birth scene, Jenkins says. One of them, possibly Aphrodite, is lying down, rather sensually, on the lap of another goddess, “stretching long in her body revealing drapery, which moulds itself like wet tissue to her ample form,” Jenkins writes. Further to the right is the head of a horse that belongs to the lunar goddess Selene, the beast is clearly exhausted from helping pull the chariot of the deity through the night sky.

The contrast between the gods in this pediment, who appear to be taking the birth of Athena in stride, and that of the mortal Greek girl, who appears to be fleeing, is striking.

Metopes

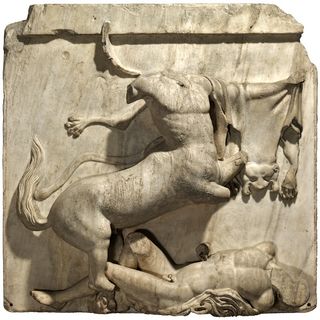

Jenkins notes that above the columns of the Parthenon there are panels carved in “high relief” each roughly four feet (1.3 meters) in width and height. They depict scenes from Greek mythology and numbered 92 in antiquity (15 are now part of the Elgin Marbles).

The examples in London come from the south of the Parthenon. They depict a battle between centaurs, creatures that are half-human and half-horse, and a legendary people known as the “Lapith.”

According to legend, the battle depicted in the Metopes broke out during a wedding feast held by the Lapith king Pirithous. The centaurs who were invited got drunk and tried to rape the Lapith women and boys. The fight was then on, “in one extraordinary slab a triumphant centaur rises up on its hind legs, exulting over the crumpled body of the Greek it has defeated,” writes Boston University professor Fred Kleiner in "Gardner’s Art through the Ages" (13th edition, Wadsworth Cengage Learning, 2010).

Frieze

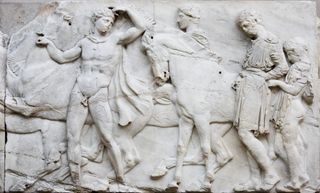

Wrapping around the top exterior of the Parthenon is a frieze carved in low relief. Originally covering about 524 feet (160 meters), about half of it is now part of the Elgin Marbles in London. It depicts a mythical procession of sorts set during the Panathenaic Festival in celebration of Athena.

The procession includes chariot races, people riding on horses, cows about to be sacrificed, girls and young women carrying ritual items, marshals supervising the procession and, of course, gods. Jenkins notes that Hermes, the son of Zeus and “runner of divine errands” is shown with a “sunhat” resting on his knee while Dionysus, god of wine, puts his “drunken arm” on Hermes shoulder. Demeter, the goddess of the harvest, has her chin on her head. She looks sad because her daughter, Persephone, has been “carried off to be bride of Hades in the underworld,” Jenkins writes. “All powerful Zeus, meanwhile, leans his arm imperiously over the back of his throne.”

Repatriation debate

There is a longstanding debate over whether the Elgin Marbles should be returned to Greece. When Lord Elgin removed the sculptures, Athens was under the control of the Ottoman Empire and had been for more than 300 years. In 1832, after a war of independence, and nearly two decades after the sculptures were removed, Greece gained its independence.

The British Museum’s position is that at the time Lord Elgin removed the sculptures, in the first decade of the 19th century, he got proper permission from the Ottoman authorities.

“In 1801 he was granted a firman (licence and letter of instruction) as a diplomatic gesture in gratitude for Britain's defeat of French forces in Egypt, then a dominion of the Ottoman Empire. The firman required the Turkish authorities in Athens not to hinder Elgin's employees in their drawing, modelling, erection of scaffolding and also allowed them to 'take away any pieces of stone with inscriptions or figures’,” says the British Museum in a statement.

“A final firman, secured by Sir Robert Adair (Ambassador in Istanbul) in February 1810 from the same authority as the earlier firman, instructed the authorities in Athens to allow the embarkation of all the remaining antiquities collected by Lord Elgin.”

The museum also argues that time had not been kind to the sculptures and Elgin had good reason to be concerned for their safety. In 1687, the Parthenon had been used by the Ottomans for gunpowder storage and the structure was badly damaged in an explosion when a Venetian force attacked the city.

The Greek government has a different view on Elgin’s actions.

“Concurrently, by showering Turks in Constantinople and Athens with gifts and money and by using methods of bribery and fraud Elgin persuaded the Turkish dignitaries in Athens to turn a blind eye while his craftsmen removed those parts of the Parthenon they particularly liked. Elgin never acquired the permission to remove the sculptural and architectural decoration of the monument by the authority of the Sultan himself, who alone could have issued such a permit,” writes the Hellenic Ministry of Culture in a statement.

“He simply made use of a friendly letter from the Kaimakam, a Turkish officer, who at the time was replacing the Grand Vizier in Constantinople. This letter, handed out unofficially as a favour, could only urge the Turkish authorities in Athens to allow Elgin's men to make drawings, take casts and conduct excavations around the foundations of the Parthenon, where some part of an inscription or relief might be buried, with the inevitable proviso that no harm be caused to the monuments.” They also argue that in removing the monuments Elgin’s team caused “considerable damage” to the sculptures and Parthenon itself.

So far the British Museum has given no indication that it intends to repatriate the sculptures but the Greek government is determined to pursue the case.

“The case of Parthenon is absolutely distinctive. The reunion of the Marbles is our debt of honor towards history,” said Georgios Voulgarakis, then minister of culture, in a 2006 speech. “The museums ought to meet their moral obligations towards the cultural and spiritual coherence of the United Europe.”

— Owen Jarus, LiveScience Contributor

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Owen Jarus is a regular contributor to Live Science who writes about archaeology and humans' past. He has also written for The Independent (UK), The Canadian Press (CP) and The Associated Press (AP), among others. Owen has a bachelor of arts degree from the University of Toronto and a journalism degree from Ryerson University.