Olympia: Site of Ancient Olympics

Olympia is an ancient Greek sanctuary in the Peloponnese region in southern Greece where every four years the ancient Olympic games were held.

Located at the intersection of two rivers, the Alpheus and the Kladeos, Olympia had a mix of religious and athletic facilities. It had a stadium, the first ever constructed, which could hold 40,000 people. It also had a hippodrome where great chariot races took place. Two nearby cities named Elis and Pisa argued, and occasionally waged war, over who had the right to control the site.

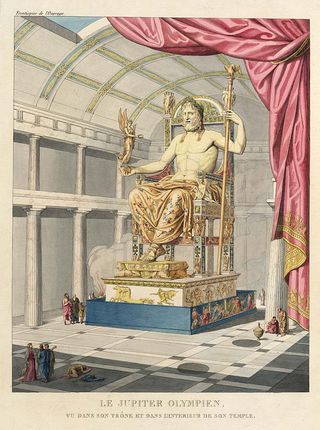

Among the religious features was one of the Seven Wonders of the World — a giant statue of Zeus made of wood, gold and ivory. The seated god had a statue of the winged goddess Nike in his right hand and a sceptre with perched eagle in his left. Kept in a temple dedicated to Zeus, the height of the long-lost statue has been estimated to be about 40 feet (12 meters).

With 40,000 people crammed to watch five days of games and religious celebrations Olympia offered a grand, and very crowded, spectacle.

The writer Epictetus, who lived about 1,900 years ago, wrote that “And what do you do at Olympia? Don’t you melt in the heat? Don’t you get jostled in the crowds? Don’t you encounter a thousand problems when you want to wash? Don’t you get soaked when it rains? Don’t you suffer from the noise, the shouting and the other hassle? But it seems to me you put up with all this because what you’re going to see is worth it.” (From Games and Sanctuaries in Ancient Greece by Panos Valavanēs, Kapon Edition, 2004)

The games would be held for more than 1,000 years until, under pressure from Christian authorities, they stopped sometime in the fifth century A.D.

Olympia’s origins

Panos Valavanēs, a professor at the University of Athens, notes in his book that the first evidence of human settlement near Olympia dates back more than 5,000 years, long before the first games took place. By 4,500 years ago, they had constructed a tumulus, a rock structure with ritual significance, which inhabitants may have used for burial.

About 3,000 years ago, a small sanctuary was constructed and became a place where people made offerings of bronze and terracotta figurines. Valavanēs notes that they include depictions of “bulls, horses, rams, deer and birds,” something which indicates that “the adorants placed themselves and their property (that is, their hunting animals and flocks) under the protection of the god,” Zeus. Later these offerings would come to include more and more weapons, something which hints at the growing importance of the military among the ancient Greek city states.

Although traditionally the first Olympic games are said to have been held in 776 B.C., archaeological evidence indicates that it could not have occurred before 700 B.C., after which a stadium and hippodrome were constructed.

The ancient Olympics

Who founded the games and why is a mystery. The ancient Greeks had several myths that described how they started. “The earliest mention of their foundation is found in the writings of Pindar [who lived 2,500 years ago],” writes Kristine Toohey and Anthony James Veal in their book The Olympic Games: A Social Science Perspective (Cab International, 2007).

“He attributed their origins to Heracles who, on his return from victory over King Augeas of Elis, founded the games at the tomb of Pelops [a king of a city named Pisa].”

However they started, they grew to encompass a five-day festival, held in mid-August, which included both boys' and men's events in a variety of sports, including foot and chariot racing, the pentathlon, wrestling, boxing and a bloody, no-holds-barred, form of mixed martial arts known as the Pankration. "They bend ankles and twist arms and throw punches and jump on their opponents," wrote the ancient writer Philostratos describing the sport.

As ancient art suggests, all the competitions, with the exception of chariot racing, were held in the nude, at least up until the period of Roman rule.

The winners were awarded with a crown of leaves (there were no second or third place medals) and a feast held in a building known as Prytaneion. It was also common for statues to be made honoring Olympic champions.

Married women, with the exception of the priestess of Demeter Chamyne, were not allowed to watch the competitions; however, as University of Cambridge professor Nigel Spivey points out in his book The Ancient Olympics (Oxford University Press, 2012), this ban was not complete. “Olympia was not completely closed to female spectators or female participants,” he writes.

Spivey notes that in the early fourth century B.C., a Spartan woman named Kyniska was the “owner-trainer” of a chariot team that won twice, an inscription records that she was the “only woman of all Greece” to take the crown.

In addition, unmarried girls were also allowed to watch the games, and Spivey notes that there was a “separate minor athletic festival in honour of Hera,” the wife of Zeus, in which they could compete. This festival included a running event and the offering of a newly woven robe to Hera. Unlike the men, the girls competed clothed, “the girls did not compete naked, but in short dresses hitched at one shoulder (or a male-style cloak) with their hair flying loose,” Spivey writes.

Temple of Hera

Olympia has a number of buildings that were used for religious ceremonies as opposed to athletics. Valavanēs notes that the earliest monumental building was dedicated, not to Zeus, but rather to his wife, Hera. Known as the Heraion, it was built around 600 B.C.

“On either end stood 6 columns, and 16 stood on the sides,” writes Valavanēs, noting that the style of the columns surviving today are Doric. “The original columns of the temple were wooden.” Among the surviving sculptures is a 1.7-foot-tall (half a meter) limestone head of Hera wearing a ribbon and headdress.

Temple of Zeus

In 476 B.C., after the Greeks had defeated an invasion attempt by the Persians, a decision was made to build, at Olympia, a temple dedicated to Zeus that would later hold his giant, wonder of the world, statue.

“The size of the building the Eleians dedicated to him surpassed all other temples on the Peloponnesus,” writes archaeologist Ulrich Sinn in his book Olympia: Culture, Sport and Ancient Festival (Markus Wiener Publishers, 2000). “It rose more than 65 feet (20 meters) above a plot of approximately 92 by 210 feet (28 by 64 meters).” It contained three rooms, an opening vestibule, a main room where the giant Zeus statue was eventually kept, and a back room which Sinn writes may have been used for lectures held by famous Greek thinkers such as the historian Herodotus.

The top of the east and west sides of the columned building have what are called “pediments,” triangular niches containing statues. On the west was a scene showing a battle between centaurs (half-human, half-horse mythological creatures) and a legendary people known as the Lapith. According to legend the centaurs got drunk at a wedding party hosted by the Lapith king and tried to rape their women and boys, and a fight broke out.

On the east pediment, Valavanēs notes, was another scene, this one depicting a chariot race between Oinomanos, king of Pisa, and Pelops, a claimant to the throne. Overseeing the event, at center, was Zeus himself.

Treasuries

Around 2,500 years ago, 12 small temple-like buildings, known today as “treasuries,” were constructed. They appear to have been built by Greek colonies to hold offerings for Zeus.

“Pausanias [an ancient writer] describes some of these precious votive objects and mentions ten treasuries, namely those of Sikyon, Syracuse, Epidamnos, Byzantium, Sybaris, Cyrene, Selinus, Metapontum, Megara and Gela,” writes archaeologist Olympia Vikatou in an online Hellenic Ministry of Culture article. “These simple buildings consist of a single chamber and a distyle [two-columned] portico,” which face “south towards the sanctuary.”

Valavanēs writes in his book that the “fact that the majority of the cities making these dedications were in southern Italy and Sicily, the Propontis, and North Africa demonstrates the extent of the sanctuary’s reputation amongst the colonies ...”

Roman Olympia and end

Valavanēs notes that after Greece was conquered in 146 B.C., the Romans were generally careful to respect Olympia. The Roman general Mummius, who oversaw the Roman troops, even made an offering of 21 gilded Greek shields, which were hung at the Temple of Zeus.

Roman citizens, including the emperor himself, were allowed to compete in the games (Nero is said to have won six contests, albeit fraudulently). New construction took place at Olympia, including inns, shops and a new, badly needed, water system.

What ultimately finished the ancient Olympics was the rise of Christianity. When it grew and became the official religion of Rome, its leaders did not take kindly to the, in their view, pagan games. In A.D. 393, an edict issued by emperor Theodosius I banned the Olympics, although it appeared to have been ignored for a time. When exactly the last games were held isn’t known but they appear to have ended at some point in the fifth century A.D.

As for the statue of Zeus, it appears to have been taken to Constantinople (now Istanbul) at some point and lost in a fire in A.D. 475.

At the site of Olympia, a Christian village would be built, overtaking the sanctuary, which was falling into ruin. “As he had done with the rest of his world, Zeus surrendered his largest sanctuary, Olympia, to Christianity,” writes Valavanēs. The games the god’s sanctuary hosted would not be revived until 1896.

— Owen Jarus, LiveScience Contributor

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Owen Jarus is a regular contributor to Live Science who writes about archaeology and humans' past. He has also written for The Independent (UK), The Canadian Press (CP) and The Associated Press (AP), among others. Owen has a bachelor of arts degree from the University of Toronto and a journalism degree from Ryerson University.