Ancient 'Super-Croc' Fossil Discovered in Museum Drawer

Long-forgotten remains of a giant dolphin-shaped crocodilian "super-predator" that could devour ancient beasts its size and larger have now been discovered in a museum drawer in Scotland, researchers say.

The ancient newfound crocodilian is named Tyrannoneustes lythrodectikos, which in ancient Greek means "blood-biting tyrant swimmer."

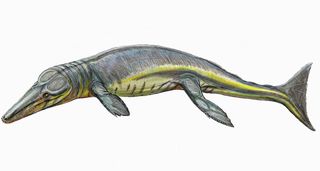

"Tyrannoneustes was a dolphinlike crocodile that lived 165 million years ago," said researcher Mark Young, a vertebrate paleontologist at the University of Edinburgh in Scotland and the University of Southampton in England.

The predator possessed a long snout, large flippers, armorless skin and a tail fin where the bottom half is larger than the top half, resembling an upside-down version of an ordinary shark's tail fin.It's uncertain how large Tyrannoneustes was, but the right side of its lower jaw was at least 26 inches (67 centimeters) long.

Tyrannoneustes was a super-predator, meaning it evolved to devour prey its size and larger. Features of its lower jaw and teeth reveal the beast was suited for swallowing smaller prey whole or slicing larger prey into pieces small enough to swallow. [Image Gallery: Ancient Monsters of the Sea]

"These features include enlarged teeth, teeth with serrated edges, and a change in the shape of the lower jaw that allowed it to open wider," Young told LiveScience.

Back when Tyrannoneustes was alive, the area in central England where the fossils were discovered was covered in a shallow sea encompassing much of what is now Europe.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

"At that time, Europe would have been an archipelago with some larger landmasses," Young said. Europe was also farther south back then, meaning sea-surface temperatures were balmy, ranging from 68 to 80 degrees Fahrenheit (20 to 27 degrees Celsius). The area Tyrannoneustes was found in also held a diverse group of other marine reptiles, such as other marine crocodilians, the vaguely Loch Ness Monster-shaped plesiosaurs and pliosaurs, and the dolphin-shaped ichthyosaurs, as well as fish and squid.

The fossils were originally discovered in clay pits by fossil hunter Alfred Leeds some time between 1907 and 1909. They languished in a drawer in the Hunterian Museum and Art Gallery in Glasgow, Scotland, until Young and his colleagues rediscovered them.

"It had lain there for almost 100 years," Young said.

No modern crocodiles are descended from Tyrannoneustes. Instead, this predator was a kind of metriorhynchid, an extinct family of marine crocodiles.

"This new species fills an evolutionary gap in the metriorhynchid fossil record," Young said. "The discovery of Tyrannoneustes shows that during the Middle Jurassic, metriorhynchid crocodiles were beginning to evolve into predators of large-bodied prey. By the Late Jurassic, numerous metriorhynchid species were suited to feeding on large prey, but Tyrannoneustes is the first known from the Middle Jurassic. How this impacted upon other predatory groups such as pliosaurs and ichthyosaurs is still unclear."

Future research can scan Tyrannoneustes bones to develop computer models of how it might have fed, Young said. He and his colleagues detailed their findings online Jan. 4 in the Journal of Systematic Palaeontology.

Follow LiveScience on Twitter @livescience. We're also on Facebook & Google+.

Most Popular