The Star Explosion That Wasn't: Astronomers Solve 150-Year-Old Mystery

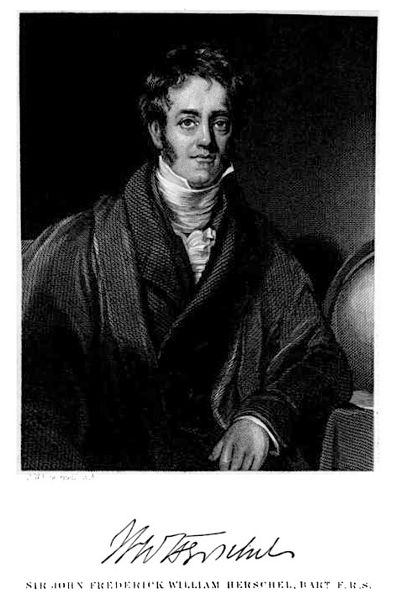

After a stellar explosion was reported in 1866, British astronomer John Herschel announced he had seen a bright flare from the same location 24 years earlier.

Herschel's claim was contested almost immediately, with some saying he had seen only a fairly common star in 1842.

Now the question of whether Herschel actually saw a recurrent supernova or a common star has finally been answered, clearing up a point about stars that "go off" periodically.

To solve the 150-year-old mystery, Bradley Schaefer of Louisiana State University dug through the records of the Royal Society in Britain, to which Herschel donated his papers. Schaefer was unable to find the astronomer's original chart, but he found the second best thing: a copy made by Herschel and sent to another astronomer a few short weeks after the 1866 explosion.

The document revealed that what Herschel observed was not the recurrent nova T Coronae Borealis (T CrB) but another star, BD+25°3020.

Blown away — again

Rather than dying in a single blaze of glory, recurrent novas cycle through explosions on a steady basis. White dwarf stars pull in material from companion stars, and they flare up when enough material has fallen onto their surfaces. Understanding just how often an individual nova, such as T Coronae Borealis (T CrB), explodes is crucial to understanding objects that could eventually evolve into Type 1a supernovas.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

But in 1866, novas were not well understood.

"When T CrB went off, the world of astronomy became ablaze," Schaefer said during a presentation in January at the 221st meeting of the American Astronomical Society. [Supernova Photos of Star Explosions]

Back in 1866, John Herschel, son of astronomer Sir William Herschel, dug through his records to find a map of the night sky he had made nearly 24 years before. But the published chart seemed to place what Herschel claimed was the explosion near the spot of another star, and generated an almost immediate response from the astronomical community.

"We had a couple of people coming up to Herschel saying, 'Hey, are you sure this isn't just the BD star?'" Schaefer said.

The recurrent nova white dwarf exploded again in 1946, which would give it a time scale of 80 years between flares. But if Herschel saw it explode in 1842, that would change the time scale of the star, and call into question astronomers' understanding of these repeating explosions.

Solving the mystery

For Schaefer, who studies recurrent novas, solving the mystery wasn't as simple as determining exactly where Herschel's mystery object sat in the sky. The BD star is too faint to be observed at sea level with the naked eye, according to Schaefer, so Herschel could not have seen it without assistance. If Herschel was relying on his own eyes to map the night sky, he must have seen T CrB — or so the argument goes.

Digging through letters, Schaefer found a notation that all of Hershel's observations weren't made unaided. On occasion, the British scientist used an opera glass, which would have allowed him to see the BD star.

Still, this wasn't definitive enough. Schaefer kept digging, searching for the original sky map.

Instead, he found a letter from Herschel to another astronomer with a diligently replicated chart.

According to Schaefer, Herschel placed a heavy piece of paper under the original chart and used pins to precisely map the location of each star in the sky. He sent the duplicate chart to the fellow astronomer.

"We have him guaranteeing it's a fair copy," Schaefer told SPACE.com.

The chart revealed that the object Hershel observed sat in the same position as the BD star, and not where T CrB lit up the sky.

"T CrB did not go off in 1842," Schaefer said, closing the door on 150-year-old mystery.

Schaefer's findings will be published in an upcoming issue of the journal The Observatory.

This story was provided by SPACE.com, a sister site to Live Science. Follow SPACE.com on Twitter @Spacedotcom. We're also on Facebook & Google+.