Ancient Magical Illusion Even More Effective Than Magicians May Realize

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

(ISNS) -- Scientists analyzing how magicians Penn & Teller perform one of the oldest known illusions now reveal that some aspects of the magic trick are even more effective at manipulating audiences than the magicians predicted.

These findings not only shed light on basic processes such as cognition, but could help advance the art of magic, researchers suggested.

In recent years, neuroscientists have increasingly been analyzing magicians' performances to gain insights on the human mind.

Article continues below"We realized that magicians were among the best people at manipulating attention and awareness, far better than scientists," said cognitive neuroscientist Stephen Macknik, director of the laboratory of behavioral neurobiology at the Barrow Neurological Institute in Phoenix, Ariz. "So we've been poaching their techniques, bringing them back to the labs to increase our rate of discovery."

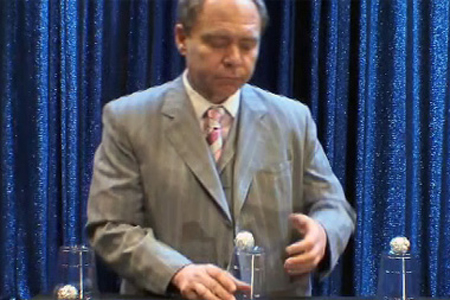

The latest magic trick Macknik and his colleagues investigated is the classic cups and balls illusion. Examples ascribed to ancient Roman conjurers date back to 3 B.C., and some claim it goes back further to ancient Egypt.

The illusion nowadays commonly involves three upside-down cups and three balls, Magicians can make the balls seemingly jump from cup to cup, disappear from one cup and appear in another, turn into other items and so on. (The modern swindler's version is the shell game.)

To learn more about this illusion, the researchers enlisted the aid of the famous duo Penn & Teller. Seven volunteers watched 10-12-second-long video clips of Teller performing the illusion in front of a NOVA scienceNOW TV crew at the duo's theater in Las Vegas.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

The balls in the illusion are typically brightly colored, while the cups are usually opaque. Penn & Teller practice a version with three opaque and then three transparent cups.

Watch Video Short: Magic and Autism on PBS. See more from NOVA scienceNOW.

"It's a great act, and the trick still works even with transparent cups, because they're just that good — people still can't follow all the movements and see how the trick is done," Macknik said.

"I've seen them do this trick for more than 20 years," said vision scientist Flip Phillips at Skidmore College, in Saratoga Springs, N.Y. "The best part of the whole routine is that, despite the fact that they are telling you what they are doing — they're showing you what they're doing — you're still amazed because you just can't fight the deception."

Teller devised this variation while fiddling with an empty water glass and wadded-up paper napkins for balls at a Midwestern diner. He turned the glass upside down and put a paper ball on top, then tilted the glass so that the ball fell into his other hand. The falling ball was so compelling that it drew his own attention away from his other hand, which was deftly and secretly loading a second ball under the glass. Teller found that the sleight happened so quickly he himself did not realize he had loaded the cup. He surmised he missed it because the falling ball captured his attention.

In the experiments, the volunteers reported when they saw balls get removed from, or placed under, cups by pressing buttons. The researchers also used cameras pointed at the eyes of the volunteers to track their gazes.

The researchers found that while the falling ball did draw audience attention, other aspects of the trick were actually stronger at making the illusion work. For instance, audiences were fooled more often when the magician attempted to drop a ball that was stuck to a cup.

"A lot of times the intuitions we have about the way things work aren't the way things work," said Phillips, who did not take part in this research. "This isn't to put down Teller — Teller's intuition is good. There is research we did on a famous sleight of hand known as the French drop where Teller's intuition on how to sell the trick is perfectly correct."

In addition, magicians often say that success with illusions depends on how well they can use gazes and faces to manipulate where audiences look, Macknik explained. The researchers tested this idea by hiding Teller's face on the video clips with a black rectangle, and found doing so apparently did not affect the illusion.

"We're showing a discovery that magicians missed because they relied on their intuition, and their intuition was wrong," Macknik said.

These findings support recent studies, including one from Macknik and his colleagues, which hinted that the facial expressions and other social cues magicians think are crucial to illusions may not actually be essential.

"A huge amount of training in magic is that social cues matter," Macknik said. "We're starting to wonder if social cues help with any magic tricks. Future research is warranted to look at the effects of social cues in illusions … we'd like to see an effect where they really matter."

These new findings shed light on how and by how much people can be misdirected, which could help magicians improve their art.

Macknik and his colleagues Hector Rieiro and Susana Martinez-Conde detailed their findings online Feb. 12 in the inaugural issue of the journal PeerJ.

Charles Q. Choi is a freelance science writer based in New York City who has written for The New York Times, Scientific American, Wired, Science, Nature, and many other news outlets.

Inside Science News Service is supported by the American Institute of Physics.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus