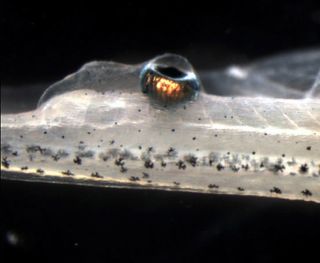

Whoa! Mutant Tadpoles Sprout Eyeballs on Their Tails

Eyes hooked up to the tail can help blinded tadpoles see, researchers say.

These findings could help guide therapies involving natural or artificial implants, scientists added.

A major roadblock when it comes to treating blindness and other sensory disorders is how much remains unknown about the nervous system and its ability to adapt to change. To learn more about the relationship between the body and the brain, researchers wanted to see how capable the brain was of interpreting sensory data from abnormal "ectopic" locations from which it normally does not receive signals.

Eye on the tail

Scientists experimented with 134 tadpoles of the African clawed frog Xenopus laevis, a common lab animal. They painstakingly grafted new eyes onto places such as their torsos and tails and then surgically removed their original eyes. [See Images of the Odd-Eyed Tadpoles]

"We do a lot of work to understand regenerative biology, and that entails experiments that change the body," researcher Michael Levin, a developmental biologist at Tufts University, told LiveScience. "We have four-headed worms, six-legged frogs, and many other unusual creatures here as part of our work on bioelectricity and organ regeneration."

These experimental tadpoles then received a vision test the researchers first refined on normal tadpoles. The tadpoles were placed in a circular arena half illuminated with red light and half with blue light, with software regularly switching what color light the areas received. When tadpoles entered places lit by red light, they received a tiny electric zap. A motion-tracking camera kept tabs on where the tadpoles were.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Remarkably, the scientists found that six tadpoles that had eyes implanted in their tails could apparently see, choosing to remain in the safer blue-light areas.

"The brain is not wired to find an eye on the tail, since it's never happened before and thus is not something the brain has evolved specifically to deal with, and yet it can recognize this patch of tissue as providing valuable visual information," Levin said.

"These findings suggest that the brain has remarkable plasticity and may actually take a survey of its body configuration to make use of different body arrangements," Levin added. "If it were not the case, then every time a mutation produced an improvement in body plan — a large significant change in anatomy — the animal would die and the beneficial mutation would be lost."

Rather, when a mutation makes a change in the body plan of an embryo, the brain-body programs that tell an eye to see and a hand to grasp, for instance, "don't suddenly become useless," Levin said. "The brain can map its activity onto a wide range of configurations of the body. This modularity makes it much easier for complex new body features to evolve."

Augmentation technology

The transplanted eyes came from tadpole donors genetically modified to generate a red fluorescent protein. As such, the researchers could see under a microscope whether these eyes sent red nerves outward in the body. Half the recipient tadpoles had no such nerves grow, while about a quarter had nerves projecting toward the gut and the other quarter had nerves extending toward their spine.

The six tadpoles that could see well all had nerves plugged into their spine, which makes sense — their eyes apparently linked with their central nervous system.

"This has implications not only for regenerative medicine — replacing damaged sensory and motor organs — but also for augmentation technology," Levin said. "Perhaps you'd like some more eyes, maybe ones that see in infrared?" [Bionic Humans: Top 10 Technologies]

One question Levin and his colleagues often get asked "is whether the tadpoles are experiencing sight from these ectopic eyes like they do from normal eyes," Levin said. "We have no idea what a tadpole is experiencing. This is a philosophical question that is not immediately tractable.

"Another thing people sometimes assume is that this capability is only for tadpoles or 'lower' animals," Levin said. "In fact, this kind of thing probably works in humans also, as evidenced by related studies over the last few years. Brain plasticity is a fundamental aspect of the function of the nervous system and its interface to the body."

The researchers seek to figure out three other aspects: which brain regions are processing the sensory data, how many extra eyes a frog brain can handle, and how the brain knows that this piece of tissue on the tail is providing visual data, and not simply indicating an infection, injury or other sense like smell, Levin said.

Levin and his colleague Douglas Blackiston detailed their findings online today (Feb. 27) in the Journal of Experimental Biology.

Follow LiveScience on Twitter @livescience. We're also on Facebook & Google+.

Most Popular