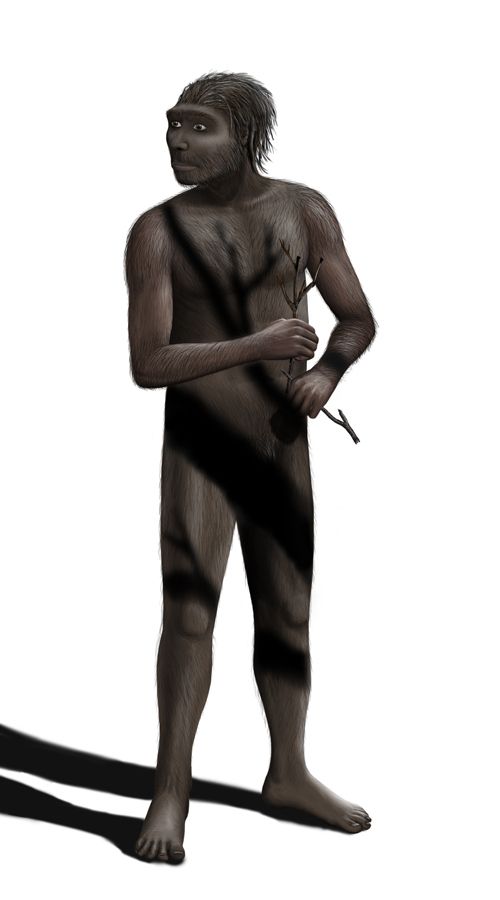

Early human ancestors needed high-level intelligence to use fire, new research suggests.

The study, published in February in the Cambridge Archaeological Journal, argues that fire use requires long-term planning, group cooperation and inhibition. In combination with evidence for early fire use, the study suggests that the early human ancestor Homo erectus may have been smarter than previously thought.

"Early humans would have had to have been fairly clever to keep a fire going by cooperating, not stealing food or not stealing fire from other people," said study author Terrence Twomey, an anthropologist at the University of Melbourne in Australia.

Fire found

Traces of ash found in Wonderwerk Cave in South Africa suggest that at least some Homo erectus used fire as far back as 1 million years ago. Another site in Israel, Gesher Benot Ya'aqov, shows evidence of fire from around 800,000 years ago. While it's possible these ancient ancestors made fire from scratch, it's more likely they learned to harness flames from a lightning strike or other natural source, Twomey told LiveScience. [Electric Earth: Stunning Images of Lightning]

Some anthropologists have suggested that cooked food allowed early human ancestors to eat meat, derive more nutrition from food and neutralize bacteria in their food. As a result, early humans could divert energy from digestion to brain growth.

But the evidence for that hypothesis is mostly circumstantial.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Fire smarts

Twomey decided to look at the question from another angle — what minimum mental abilities would human ancestors need to regularly maintain fire?

Quite a lot, it turns out.

Lacking the ability to make fire from scratch, to keep fires going, Homo erectus needed long-range planning abilities far and above those needed for fashioning primitive stone tools or hunting prey. They would need to gather firewood several days before the fire might die, or anticipate gathering storms and protect fragile flames.

Using fire also requires the self-control to avoid eating food until it's cooked, a test chimpanzees would fail abysmally.

What's more, human ancestors would need fairly advanced social skills to make sure others didn't steal cooked food or a fire while its original tender was out gathering firewood, Twomey said.

"It's not simply a matter of keeping a fire going by tossing some sticks on it," Twomey told LiveScience.

As a result, if Homo erectus tended fires 1 million years ago, it would suggest the early human ancestors were smarter than previously thought, he said.

Test of intelligence

The new research paper lays out a framework for experimentally testing the minimal cognitive abilities that our ancestors would have needed to keep fires, said Richard Wrangham, a biological anthropologist at Harvard University and the author of "Catching Fire: How Cooking Made Us Human" (Basic Books, 2010), who was not involved in the study.

Still, the study doesn't prove that human ancestors possessed those abilities 1 million years ago, said Ian Tattersall, an anthropologist at the American Museum of Natural History in New York, who was not involved in the study.

"You've got to be smarter than an ape to domesticate and use fire, there's no question about it," Tattersall told LiveScience. "But we don't really know when the use of fire became a routine part of hominid life."

Follow Tia Ghose on Twitter @tiaghose. Follow LiveScience on Twitter @livescience, Facebook & Google+. Original article on Live Science.

Tia is the managing editor and was previously a senior writer for Live Science. Her work has appeared in Scientific American, Wired.com and other outlets. She holds a master's degree in bioengineering from the University of Washington, a graduate certificate in science writing from UC Santa Cruz and a bachelor's degree in mechanical engineering from the University of Texas at Austin. Tia was part of a team at the Milwaukee Journal Sentinel that published the Empty Cradles series on preterm births, which won multiple awards, including the 2012 Casey Medal for Meritorious Journalism.