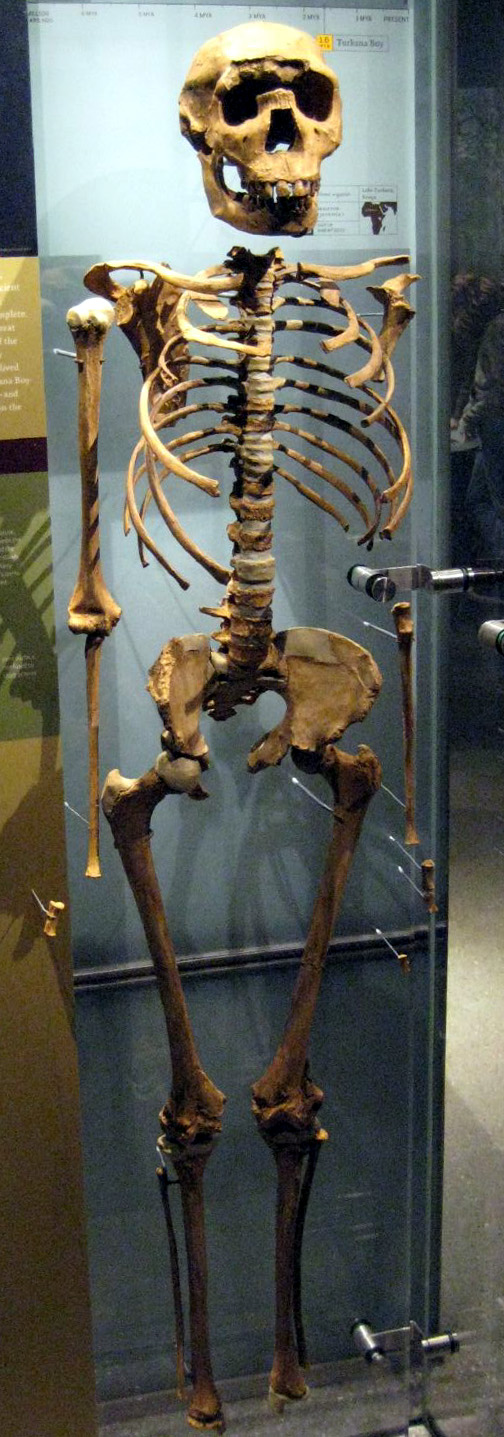

"Turkana Boy," an exquisitely preserved 1.5-million-year-old human ancestor found in Kenya, may not have had dwarfism or scoliosis, new research suggests.

Past studies had suggested that the ancient human ancestor, a Homo erectus, had suffered from a congenital bone disorder that made him unrepresentative of his species.

"Until now, the Turkana Boy was always thought to be pathological," said study co-author Martin Häusler, a physician and physical anthropologist at the University of Zurich. "The spine was somewhat weird, and so he couldn't be used as a comparative model for Homo erectus biology because he was so pathological."

But the new analysis, published in the March issue of the American Journal of Physical Anthropology, suggests that apart from a herniated disc in his back, Turkana Boy was a fairly healthy person with no genetic bone problems. [The 9 Most Bizarre Medical Conditions]

Exquisite find

The exquisitely preserved fossil, unearthed near the shores of Lake Turkana in Kenya in 1984, is the most complete early human skeleton ever found. The ancient hominid was likely a child or an adolescent Homo erectus who lived and died about 1.5 million years ago.

But about a decade ago, researchers proposed that Turkana Boy was suffering from a congenital deformation of the spine —possibly dwarfism or scoliosis.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

To find out, Hausler and his colleagues carefully reanalyzed the skeletal bones. When they arranged the ribs as they were originally laid out, they got an asymmetrical back and rib cage.

"The ribs were arranged in the wrong way originally, and then you get this asymmetry, which is essentially not there," Häusler told LiveScience.

By rearranging the bones, the researchers found that Turkana Boy actually had a symmetrical spine and rib cage, meaning he wasn't suffering from dwarfism or scoliosis. As a result, it's fair game to make conclusions about the species' anatomy based on the skeleton, Häusler said.

The ancient hominid did show evidence of some vertebral misalignment, consistent with having a herniated disc — an injury that may have contributed to his death, Häusler said.

Controversial results

The new study is an excellent analysis, wrote Henry McHenry, an anthropologist at the University of California, Davis, who was not involved in the study. Häusler "has a special perspective in being an orthopedic surgeon with years of experience with original fossils in Africa and huge collections of modern humans and apes."

But not everyone is convinced.

"His axial skeleton is distinctive and bears evidence of some significant pathology," wrote Scott Simpson, an anthropologist at Case Western Reserve University in Ohio who was not involved in the study, in an email. "Clearly, some of the characteristics recognized in [Turkana Boy] would be characterized as congenital pathologies, perhaps in addition to traumatic injuries."

Follow Tia Ghose on Twitter @tiaghose. Follow LiveScience @livescience, Facebook & Google+. Original article on LiveScience.com

Tia is the managing editor and was previously a senior writer for Live Science. Her work has appeared in Scientific American, Wired.com and other outlets. She holds a master's degree in bioengineering from the University of Washington, a graduate certificate in science writing from UC Santa Cruz and a bachelor's degree in mechanical engineering from the University of Texas at Austin. Tia was part of a team at the Milwaukee Journal Sentinel that published the Empty Cradles series on preterm births, which won multiple awards, including the 2012 Casey Medal for Meritorious Journalism.