Google Predicts Stock-Market Crashes, Study Suggests

On Tuesday (April 23), a tweet from a hacked Associated Press account claiming there had been explosions at the White House sent the Dow Jones Industrial Average plummeting 145 points almost instantaneously. The incident was an example of how quickly the Internet can send shock waves through the financial world, given how many trades are completed by computers rather than humans.

But new research finds the financial world doesn't just respond to the Internet; the Internet can also predict what the stock market will do. The research isn't the first to find such online clairvoyance. For example, Google may even be able to predict medication side effects before doctors can, thanks to people's tendencies to self-diagnose using the search engine. Google searches can also forecast the spread of the flu.

The new study, however, takes the extra step of testing out how well stock-buying would go, using Google search trends as guidance. The result: a pretty nice return.

Googling the markets

University of Warwick Business School researcher Tobias Preis and colleagues had previously found a correlation between the number of Google searches for a company's name and the number of times that company's stock was bought and sold. However, that method couldn't predict a stock's price. [The 10 Most Disruptive Technologies]

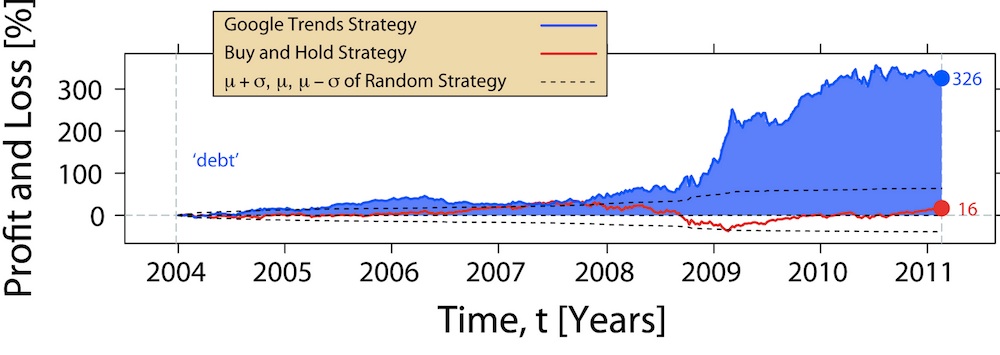

Now, Preis and his colleagues have turned to broader search trends to try to predict the whole stock market's movements. Using publicly available data on search terms from Google Trends, the researchers tracked 98 terms, many of them finance- or economics-related, such as "debt," "crisis" and "derivatives" from 2004 to 2011. They then compared the searches to the closing prices of the Dow Jones Industrial Average, a major stock-market index.

To test whether the terms searched in the week prior to any given closing day could predict the Dow Jones, the researchers invented a pretend investing game. If searches for financial terms went down, they opted to buy stocks and take a "long" position, holding on to the stocks and waiting for their value to go up.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

If searches for financial terms went up, the researchers instead chose to "short" the market — a strategy that allows buyers to sell stocks they don't own, with the understanding that they will buy the stocks later at a lower price — in essence, gambling that the stocks are going to fall in value.

Worried searchers

The reasoning behind the game was simple. If people get anxious about the stock market, they will likely seek out information on financial issues before trying to dump their stock. Thus, finance-related Google searches should go up before a stock market decline.

That's exactly what the researchers found: An uptick in Google searches on finance terms reliably predicted a fall in stock prices.

"Debt" was the most reliable term for predicting market ups and downs, the researchers found. By going long when "debt" searches dropped and shorting the market when "debt" searches rose, the researchers were able to increase their hypothetical portfolio by 326 percent. (In comparison, a constant buy-and-hold strategy yielded just a 16 percent return.)

"Trends to sell on the financial market at lower prices may be preceded by periods of concern," the researchers write today (April 25) in the journal Scientific Reports. "During such periods of concern, people may tend to gather more information about the state of the market. It is conceivable that such behavior may have historically been reflected by increased Google Trends search volumes for terms of higher financial relevance."

Nevertheless, the average day-trader might find the strategy tough to implement, Preis said.

"This is something I wouldn't recommend to do without testing this very carefully," Preis told LiveScience. For one thing, markets have a tendency to adapt. If everyone starts using Google search terms to try to game the system, the strategy will become less effective.

For another, the financial terms used by the researchers may no longer be the best predictors of how buyers and sellers are feeling.

"You would need to find a way to identify, on the fly and in real time, what are the emerging topics that are relevant to markets?" Preis said.

The findings are scientifically "truly exciting," Preis said, because they have implications far beyond the stock market. Online chatter could help predict disease spread, civil unrest and political elections, he said. And Google is only the beginning, he added. Wikipedia, for example, provides open-source information on how many people view specific articles hour-by-hour, making the online encyclopedia another potential predictor of stock markets and other real-life behavior.

Follow Stephanie Pappas on Twitter and Google+. Follow us @livescience, Facebook & Google+. Original article on LiveScience.com.

Stephanie Pappas is a contributing writer for Live Science, covering topics ranging from geoscience to archaeology to the human brain and behavior. She was previously a senior writer for Live Science but is now a freelancer based in Denver, Colorado, and regularly contributes to Scientific American and The Monitor, the monthly magazine of the American Psychological Association. Stephanie received a bachelor's degree in psychology from the University of South Carolina and a graduate certificate in science communication from the University of California, Santa Cruz.