Earliest Great Ape Had Posture Like Humans, Fossils Suggest

The oldest known hip from a great ape is now shedding light on the evolution of hominids, revealing the ancient creature may have adopted the upright posture often linked with humans and living great apes, researchers say.

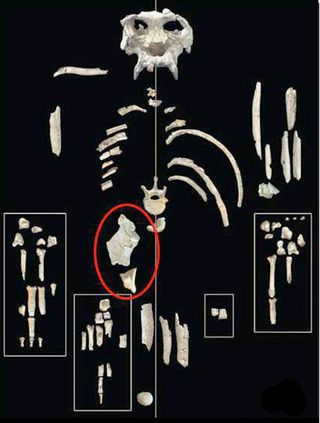

Scientists discovered the fossil skeleton of an ape near Barcelona in Catalonia in northeastern Spain in 2002, when a bulldozer was clearing the land for digging. They named it Pierolapithecus catalaunicus, or the ape from near the village of Els Hostalets de Pierola in Catalonia.

The researchers estimate the ape lived about 11.9 million years ago. Analysis of its skeleton and teeth suggest it was male, weighed about 77 lbs. (35 kilograms) and dined on fruit. [In Photos: A Game-Changing Primate Discovery]

Ancient ape bones

The great ape family, which includes gorillas, orangutans, chimpanzees, bonobos and humans, is thought to have diverged from the lesser apes, which include modern gibbons, about 11 million to 16 million years ago. The age of the fossil and a prior study of Pierolapithecus' wrist, spine, rib cage and shoulder hintedit could be the last relative the great ape family had in common.

"It provides us with information about the condition of the earliest great apes — what they looked like, how they behaved and moved about the environment, what their diet might have consisted of," researcher Ashley Hammond, a biological anthropologist at the University of Missouri at Columbia, told LiveScience.

For instance, Pierolapithecus'shoulder blades lie along its back just like those of modern great apes and humans; but in monkeys, the shoulder blades rest on the sides of the rib cage, like in dogs. Moreover, like modern great apes, Pierolapithecushas a wider and flatter rib cage than monkeys and a relatively short and stiff lower spine that would make it easier to assume an upright posture to climb vertically. It also had flexible wrists like apes and humans, although it kept the relatively short fingers and toes of monkeys, suggesting it did not do a lot of hanging from trees.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Straight walker

Now the first analysis of the ape's pelvis reveals Pierolapithecus had even more in common with the great ape family than previously thought, adopting an upright posture more often than monkeys.

Hammond employed a tabletop laser scanner attached to a turntable to capture detailed surface images from all sides of the fossil. The laser-scanning data helped the researchersdevelop a 3D model to compare the pelvis anatomy of Pierolapithecus with living and extinct species. Hammond and her colleagues focused on the pelvis because it can reveal a lot about how a creature moves and is key to virtually all discussions of human origins.

The researchers found that in Pierolapithecus, the ilium, the largest bone in the pelvis, is wider than that found in most monkeys or a more ancient, monkeylike ape, Proconsul nyanzae, which lived about 18 million years ago. This wider pelvis could have made Pierolapithecus more like an ape than a monkey and helped with balance and stability. Also, the shape of an important attachment point for back muscles in the ilium appeared to lie between those found in monkeys and great apes.

Altogether, Pierolapithecus' pelvis suggests it could have adopted an upright posture more often than monkeys, but less often than modern great apes. In addition, the pelvis in this early great ape does not look evolved for a life spent hanging from trees, a key trait distinguishing all living species of apes from their monkey relatives. This suggests the behavior evolved later in great apes and not from a common ancestor, but perhaps independently within multiple lineages.

"The research on Pierolapithecus is ongoing," Hammond said. "There are still regions of the skeleton that deserve additional study in order to gain insight into this particular species."

In addition to Pierolapithecus, "there are many other understudied species of fossil apes in Spain and in other regions of Europe, Asia and Africa," Hammond said. "More laboratory and field-based research is necessary in order to understand more about how apes, and later humans, evolved."

The scientists detailed their findings online March 30 in the Journal of Human Evolution.

Follow us @livescience, Facebook & Google+. Original article on LiveScience.com.