Atmospheric Carbon Dioxide Breaks 3-Million-Year Record

The proportion of carbon dioxide in the atmosphere broke 400 parts per million Thursday (May 9), according to one of the best climate records available.

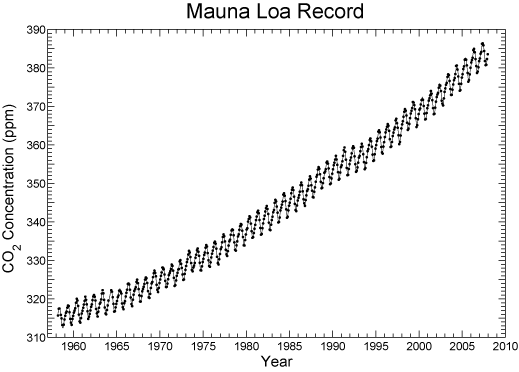

The Keeling Curve, a daily record of atmospheric carbon dioxide, has been running continuously since March 1958, when a carbon dioxide monitor was installed at Mauna Loa in Hawaii. On the first day, the observatory measured a carbon dioxide concentration of 313 parts per million (ppm). The number means there were 313 molecules of carbon dioxide in the air per every million air molecules.

Now, the Keeling Curve has reached 400 ppm for the first time in human history, with a new measure of 400.03 ppm. The data are preliminary, pending quality control checks, according to the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA). [The Reality of Climate Change: 10 Myths Busted]

The rollover from 399 won't make an appreciable difference in climate by itself, but the continuing rise in greenhouse gas concentration is already doing so, climate scientists say.

A concentration of 400 ppm is "a new high-water mark, of course, and more than anything else, has symbolic significance," said Michael Mann, a climate researcher at Pennsylvania State University.

Upward creep

Each year, the Keeling Curve shows an increase in carbon dioxide in the atmosphere which peaks in May. The number then drops, reaching a minimum in October. This maximum-minimum pattern, repeated seasonally, reveals how trees withdraw carbon dioxide from the air in summer to grow and then release it through dead, decaying leaves and wood in the winter.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

But humans release carbon dioxide into the air, too, by burning fossil fuels. This activity has caused the Keeling Curve to creep ever upward since 1958: The lows get a little higher each year, as do the highs.

"It is a reminder of just how uncontrolled this dangerous experiment we're playing with the planet really is," Mann told LiveScience.

What 400 ppm means

In the 1,000 years before the Industrial Revolution of the 18th century, atmospheric carbon dioxide held steady at around 270 to 280 parts per million.

Scientists believe that the most recent period with a 400 ppm level of carbon dioxide in the atmosphere was the Pliocene, between five million and three million years ago, according to the Scripps Institution of Oceanography, which keeps track of the Keeling Curve.

It was a different world. Global average temperatures were between 5.4 and 7.2 degrees Fahrenheit (3 to 4 degrees Celsius) higher than today, and sea level was as much as 131 feet (40 meters) higher in some places. Even the least-affected regions saw sea-level rises 16 feet (5 meters) higher than today's.

A major difference, though, is the speed at which carbon dioxide is rising today. Typically, the Keeling Curve shows increases of 2 to 2.5 ppm a year, Mann said. In the 1950s and 1960s, carbon dioxide increased by less than 1 ppm each year, according to Scripps Institution of Oceanography.

"We're on course for more than 450 ppm in a matter of decades if we don't get our fossil fuel emissions under control quite soon," Mann said.

Follow Stephanie Pappas on Twitter and Google+. Follow us @livescience, Facebook & Google+. Original article on LiveScience.com.

Stephanie Pappas is a contributing writer for Live Science, covering topics ranging from geoscience to archaeology to the human brain and behavior. She was previously a senior writer for Live Science but is now a freelancer based in Denver, Colorado, and regularly contributes to Scientific American and The Monitor, the monthly magazine of the American Psychological Association. Stephanie received a bachelor's degree in psychology from the University of South Carolina and a graduate certificate in science communication from the University of California, Santa Cruz.