Plague Helped Bring Down Roman Empire, Graveyard Suggests

Plague may have helped finish off the Roman Empire, researchers now reveal.

Plague is a fatal disease so infamous that it has become synonymous with any dangerous, widespread contagion. It was linked to one of the first known examples of biological warfare, when Mongols catapulted plague victims into cities.

The bacterium that causes plague, Yersinia pestis, has been linked with at least two of the most devastating pandemics in recorded history. One, the Great Plague, which lasted from the 14th to 17th centuries, included the infamous epidemic known as the Black Death, which may have killed nearly two-thirds of Europe in the mid-1300s. Another, the Modern Plague, struck around the world in the 19th and 20th centuries, beginning in China in the mid-1800s and spreading to Africa, the Americas, Australia, Europe and other parts of Asia. [In Photos: 14th-Century 'Black Death' Graveyard]

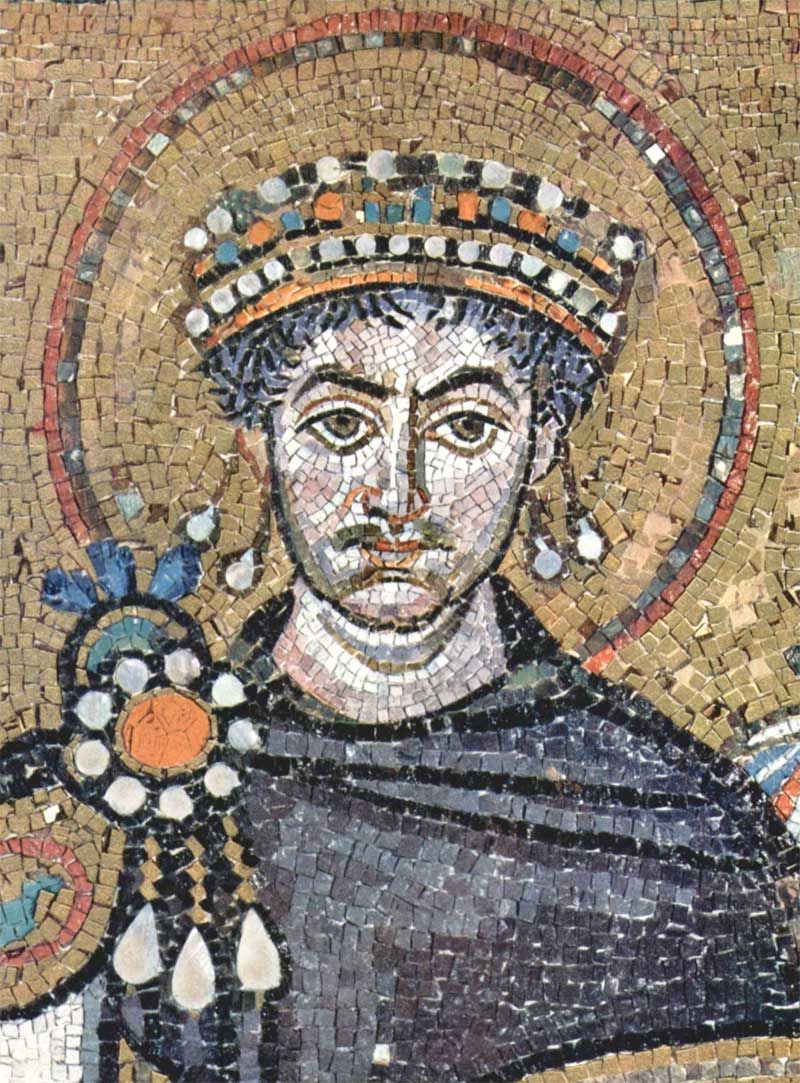

Although past studies confirmed this germ was linked with both of these catastrophes, much controversy existed as to whether it also caused the Justinianic Plague of the sixth to eighth centuries. This pandemic, named after the Byzantine emperor Justinian I, killed more than 100 million people. Some historians have suggested it contributed to the decline of the Roman Empire.

To help solve this mystery, scientists investigated ancient DNA from the teeth of 19 different sixth-century skeletons from a medieval graveyard in Bavaria, Germany, of people who apparently succumbed to the Justinianic Plague.

They unambiguously found the plague bacterium Y. pestis there.

"It is always very exciting when we can find out the actual cause of the pestilences of the past," said researcher Barbara Bramanti, an archaeogeneticist at Johannes Gutenberg University in Mainz, Germany.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

"After such a long time — nearly 1,500 years, one is still able to detect the agent of plague by modern molecular methods," researcher Holger Scholz, a molecular microbiologist at the Bundeswehr Institute of Microbiology in Munich, Germany, told LiveScience.

The researchers said these findings confirm that the Justinianic Plague crossed the Alps, killing people in what is now Bavaria. Analysis of the DNA suggests that much like the later two pandemics of plague, this first pandemic originated in Asia, "even if historical records say that it arrived first in Africa before spreading to the Mediterranean basin and to Europe," Bramanti told LiveScience.

After the Modern Plague spread worldwide, it became entrenched in many rural areas, and the World Health Organization still reports thousands of cases of plague each year. However, doctors can now treat it with modern antibiotics.

The researchers now hope to reconstruct the whole genome sequence of the plague strain in these ancient teeth to learn more about the disease, Scholz said.

The scientists detailed their findings online May 2 in the journal PLOS Pathogens.

Follow us @livescience, Facebook & Google+. Original article on LiveScience.com.