Nature Aids Science to Take on Bed Bugs

This Research in Action article was provided to LiveScience in partnership with the National Science Foundation.

Taking up the fight against bed bugs, research scientists have looked to old European folk practice — kidney bean leaves. First, they identified precisely how the leaves trap the bugs and then they created synthetic leaf traps, or biomimetic plastic surfaces.

Traditionally in Bulgaria, Serbia and other southeast European countries, households with infestations of bed bugs have thwarted the evasive little bloodsuckers by strewing kidney bean leaves on the floor at night. In the morning, the bed-bug-studded leaves are swept up and burned in piles.

This method was documented scientifically in the 1940s. But World War II interrupted that line of inquiry and, with the advent of the pesticide DDT, bed bugs became less of a problem in many places.

But, as many people are aware, the 1990s saw the beginnings of a bed bug resurgence in cities all around the world and the parasites remain a growing problem. Hotels, motels, airports, movie theaters, hospitals and many more public and private spaces have been affected. What's worse, the bugs demonstrate increasing pesticide resistance.

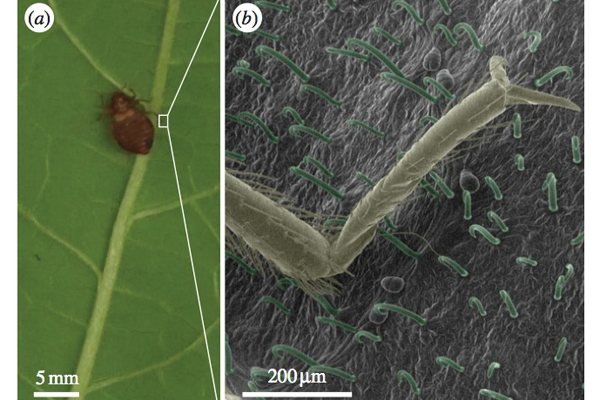

Entomologist Catherine Loudon and her colleagues at University of California, Irvine, with fellow researchers at the University of Kentucky used videography and scanning electron microscopy to investigate the possibility of creating synthetic leaf traps as a sustainable and nontoxic effective solution.

After tipping the bugs out of vials onto the underside of kidney bean leaves, the scientists found that tiny sharp-edged hairs known as trichomes actually impaled the bugs' feet. "When you put a bed bug on a bean leaf, and it takes a few steps — and this actually happens fairly rapidly, I was rather astonished — . . . it starts to struggle," Loudon said on public radio program As It Happens. The leaf acts "like a little, tiny, miniature fish hook," she said.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

The scientists then fabricated surfaces out of plastic that are similar to the leaf surfaces — "geometrically indistinguishable," Loudon said.

Unfortunately, these biomimetic surfaces don't do the trick quite yet--they snag the bugs but don't trap them. "As yet we have not been able to replicate all of the necessary mechanical properties of the microscopic bean leaf trichomes in our synthetic surfaces," Loudon said.

In the published study, the scientists explained that the trichomes they fabricated may not be bending or twisting in the precise way needed to pierce the bugs' feet and hold them. " ... [T]he tip of a more flexible hollow natural trichome could more readily skitter along the cuticle of a bug's surface until the sharp point ended up in a crevice or pit, leading to piercing, while a stiffer solid synthetic trichome may simply bend away," they wrote.

The researchers are working on modifications that will address these issues.

"Hopefully," Loudon said, "this technology could help relieve some of the problems that the burgeoning pesticide-resistant bed bug populations are causing internationally. It's a horrible problem and it's causing a lot of distress — financial, social, psychological — for a large number of people."

Doctoral student Megan Szyndler, Loudon and chemist Robert Corn of UC Irvine and entomologists Kenneth Haynes and Michael Potter of the University of Kentucky collaborated on the study.

Editor's Note: Any opinions, findings, and conclusions or recommendations expressed in this material are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of the National Science Foundation. See the Research in Action archive.