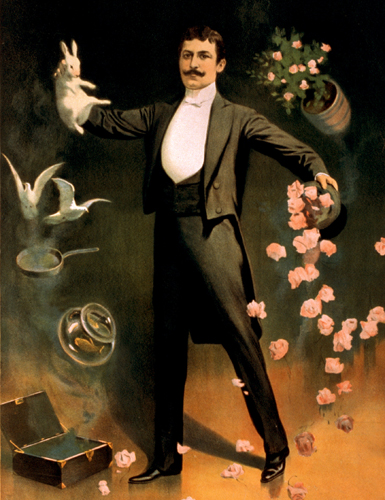

How Sleight-of-Hand Magicians Trick Our Brains

When watching an expert magician make a playing card vanish, pick-pocket a volunteer or perform any other startling sleight-of-hand trick, it seems that the harder you try to pay attention to their lightning fingers, the more easily you're fooled.

This is no coincidence. As you will learn on "Brain Games," a new series on the National Geographic Channel that illustrates the minor miracles required to pay attention and form memories, brains run on just 12 Watts of power. That's about a third of the amount used by an average refrigerator lightbulb. Such limited resources make us highly susceptible to trickery , because it only allows us to concentrate on one thing at a time. Magicians utilize people's inherent single-mindedness to great effect.

Brains have two kinds of attention. The first, called "top-down" or decision-making attention, is what you use when you decide to focus on a stimulus or task (such as this article). Top-down attention is controlled by the part of the brain called the prefrontal cortex. Second, we employ "bottom-up" or surprise attention when we quickly shift our focus onto an unexpected stimulus, such as a ringing phone. This is a more primitive response system controlled in areas of the brain called the sensory cortices.

Magicians trick you by occupying both forms of your attention. Left with no others, you're completely and hopelessly distracted from their sleights-of-hand.

In "Brain Games," a sleight-of-hand artist named Apollo Robbins, who once made headlines by pick-pocketing Secret Service agents who were accompanying former President Jimmy Carter, says, "Distracting people can be quite simple." [Why We Zone Out ]

Robbins employs "top-down distractions" by getting people to focus either on a conversation or on his actions. By being entertaining or just confusing he demands their attention. Meanwhile, on the side, he quietly removes their watches or scarves. "If I need to steal from a difficult spot, I like to use a 'bottom-up' attention strategy to direct the focus," Robbins says. Clapping loudly, a sudden movement, or in an example demonstrated in the show, waving a spoon in the air, are all examples of such strategies.

You might think that you, unlike most other people, wouldn't fall for such simple strategies, because you're a multitasker you can pay close attention to several things at once. However, according to experts, multitasking is an illusion.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

"Realistically, we can only process one thing at a time. We're effectively 'serial processors,'" says David Strayer, a psychologist who conducts research on attention at the University of Utah. "When we try and multitask, we're just switching from one activity to another."

Despite the fact that brain scans show we can only focus on one thing at a time, Strayer explained, people often have the illusion that they're balancing all their tasks equally, and performing well at all of them. "You become blind to your own impaired performance," he said.

This may be why it's so frustrating when you fail to catch a magician in their act. You really thought you were paying attention to everything so how did they manage to trick you?

An encore presentation of "Brain Games" airs this Thursday, Oct. 13 at 8 pm ET/PT.

Natalie Wolchover was a staff writer for Live Science from 2010 to 2012 and is currently a senior physics writer and editor for Quanta Magazine. She holds a bachelor's degree in physics from Tufts University and has studied physics at the University of California, Berkeley. Along with the staff of Quanta, Wolchover won the 2022 Pulitzer Prize for explanatory writing for her work on the building of the James Webb Space Telescope. Her work has also appeared in the The Best American Science and Nature Writing and The Best Writing on Mathematics, Nature, The New Yorker and Popular Science. She was the 2016 winner of the Evert Clark/Seth Payne Award, an annual prize for young science journalists, as well as the winner of the 2017 Science Communication Award for the American Institute of Physics.