Baby Neanderthal Breast-Fed for 7 Months

A baby Neanderthal who lived in what is now Belgium about 100,000 years ago started eating solid food at 7 months old, revealing a new aspect of the evolution of breast-feeding.

The precision of this estimate is courtesy a new technique that uses elements in teeth to determine when breast-feeding started and stopped. Though researchers can't be sure the young Neanderthal's pattern was typical of its kind, such a breast-feeding pattern is not unlike that seen in many modern humans.

"Breast-feeding is such a major event in childhood, and it's important for so many reasons," study researcher Manish Arora, a research associate at Harvard's School of Public Health, told LiveScience. "It's a major determinate of child health and immune protection, so breast-feeding is important both from the point of view of studying our evolution as well as studying health in modern humans." [The Facts on Breast-Feeding (Infographic)]

Reconstructing breast-feeding

Until now, however, no one had an effective way of looking at bones and reconstructing breast-feeding history. Past attempts had relied on moms' memories of when they started supplementing breast milk with solid food and when they weaned their babies. Those memories can be fuzzy years after the fact, Arora said.

He and his colleagues had an advantage: A large study of pregnant women in Monterey County, Calif., that started when the women were only 20 weeks along in their pregnancies and followed them for years. At seven years and onward, the mothers were asked to donate a baby tooth their child had lost. Arora and his colleagues analyzed the teeth for biomarkers that matched changes in the child's breast-feeding status. The researchers also conducted a similar analysis in macaques.

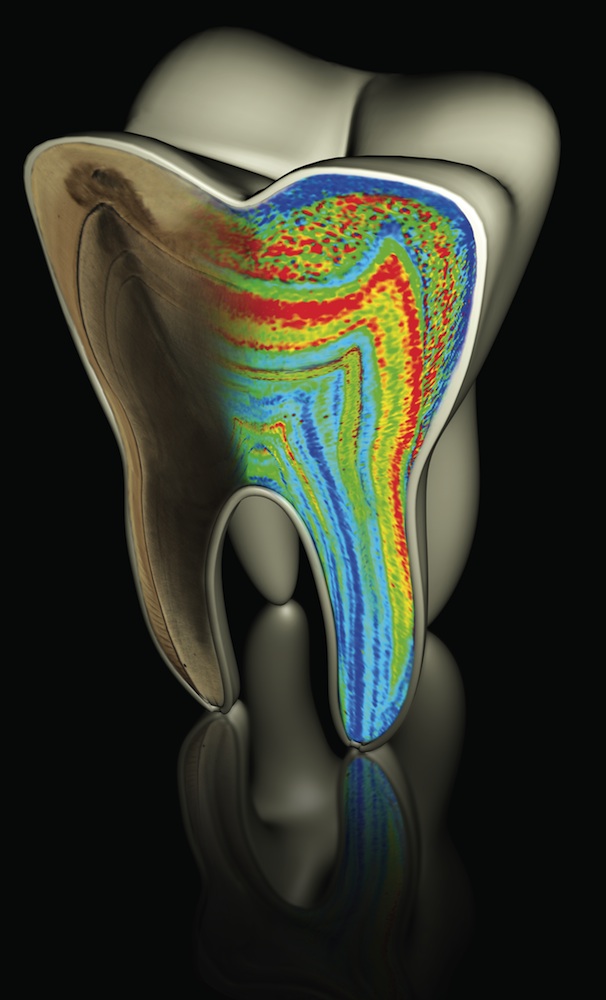

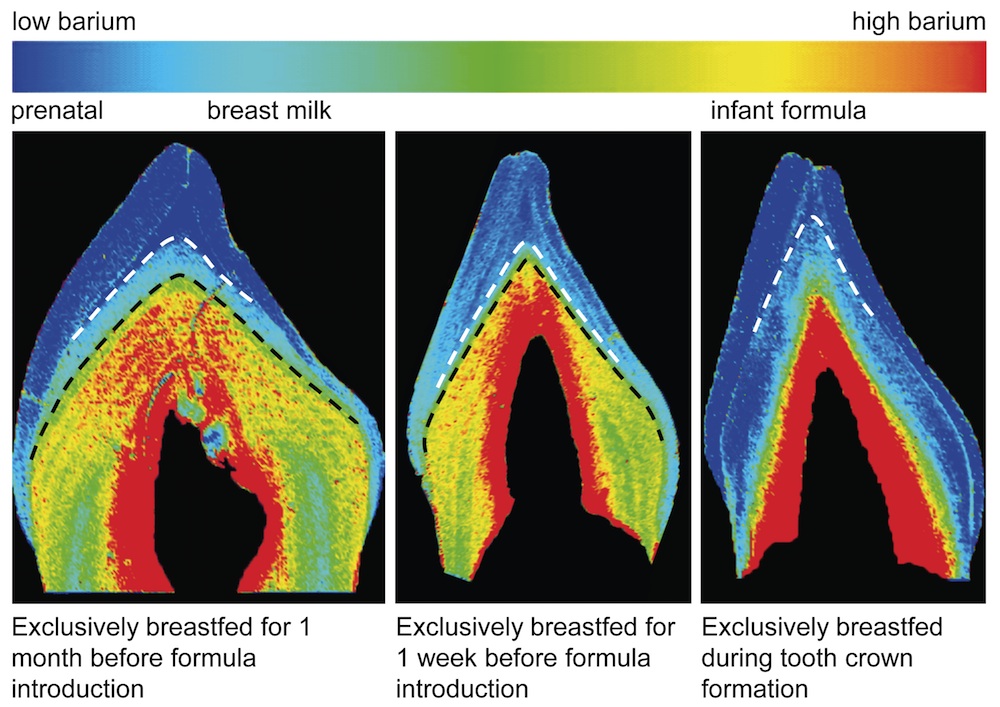

They found that both in humans and macaques, the ratio of the elements barium and calcium in the teeth revealed what the baby had been eating when those teeth formed. The researchers analyzed the enamel (the outer layer of the tooth) and the dentine (the mineralized layer that supports the enamel).

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

The parts of the teeth that form in the gums before birth have very little barium, Arora said, probably because only a small amount of the element gets into the fetus through the placenta. After birth, barium spikes and stays high in the tooth enamel and dentine. If a baby transitions to formula, the barium levels get even higher, as formula has even higher levels of barium than breast milk. [10 Scientific Tips for Raising Happy Kids]

The profile changes again when babies (or macaques) start adding solid food to their diet of breast milk.

"You find the amount of barium we can absorb from solid foods such as vegetables and meats is different from what we get from breast milk, so we can see this period of exclusive breast-feeding," Arora said.

The researchers could pinpoint weaning with great precision. For example, researchers knew one baby macaque had been separated from its mother and abruptly weaned at 166 days of life. The tooth analysis method estimated that this weaning occurred between 151 and 183 days of life — a matter of just weeks' difference from the actual date.

A baby Neanderthal's meals

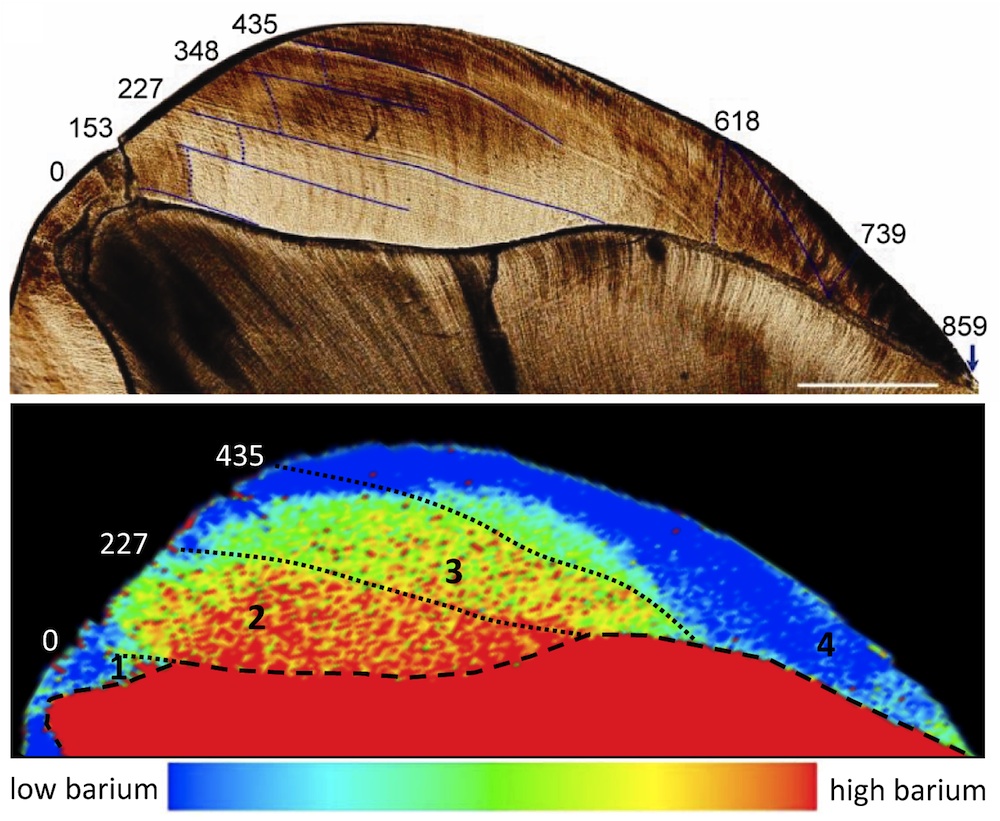

Barium has the advantage of resiliency compared with other elements, so Arora and his colleagues tested their new method on a very old tooth. They used a molar from the Scladina Neanderthal, a fossilized juvenile found in Belgium.

Similar patterns as in humans and macaques appeared: a barium increase at birth, which stayed high until the Neanderthal was about 7 months old. At that point, the tooth indicated, the Neanderthal baby went into a transitional diet, consuming breast milk supplemented by solid food. The pattern is one that today's parenting experts would likely approve. The American Academy of Pediatrics recommends exclusively breast-feeding babies for at least six months after birth, followed by the gradual introduction of solid foods.

The Neanderthal's mixed diet continued for seven months until 14 months of age, when the baby abruptly weaned. No one knows what happened, Arora said. It's possible the Neanderthal became separated from its mother, or perhaps the mother got pregnant or gave birth to a younger sibling and cut her older child off from the breast.

So far, Arora and his colleagues have tested only the Scladina Neanderthal, and they aren't sure whether its weaning pattern is typical of the species.

"We would very much like to do this on more Neanderthal samples and even beyond Neanderthal samples, on other extinct primates leading up to modern humans," Arora said. The goal would be to create an evolutionary map of breast-feeding practices in primates, he said.

This line of research could also reveal insights into the long-term health effects of breast-feeding. Researchers could recruit children with and without certain health conditions and look at their teeth for an objective measure of how long they were breast-fed, Arora said.

The researchers report their findings Thursday (May 23) in the journal Nature.

Follow Stephanie Pappas on Twitterand Google+. Follow us @livescience, Facebook& Google+. Original article on LiveScience.com.

Stephanie Pappas is a contributing writer for Live Science, covering topics ranging from geoscience to archaeology to the human brain and behavior. She was previously a senior writer for Live Science but is now a freelancer based in Denver, Colorado, and regularly contributes to Scientific American and The Monitor, the monthly magazine of the American Psychological Association. Stephanie received a bachelor's degree in psychology from the University of South Carolina and a graduate certificate in science communication from the University of California, Santa Cruz.