Deep-Sea Worms Can't Take the Heat

Hot pink tube worms living on scalding deep-sea hydrothermal vents actually like to keep things relatively cool, according to a study published today (May 29) in the journal PLOS ONE.

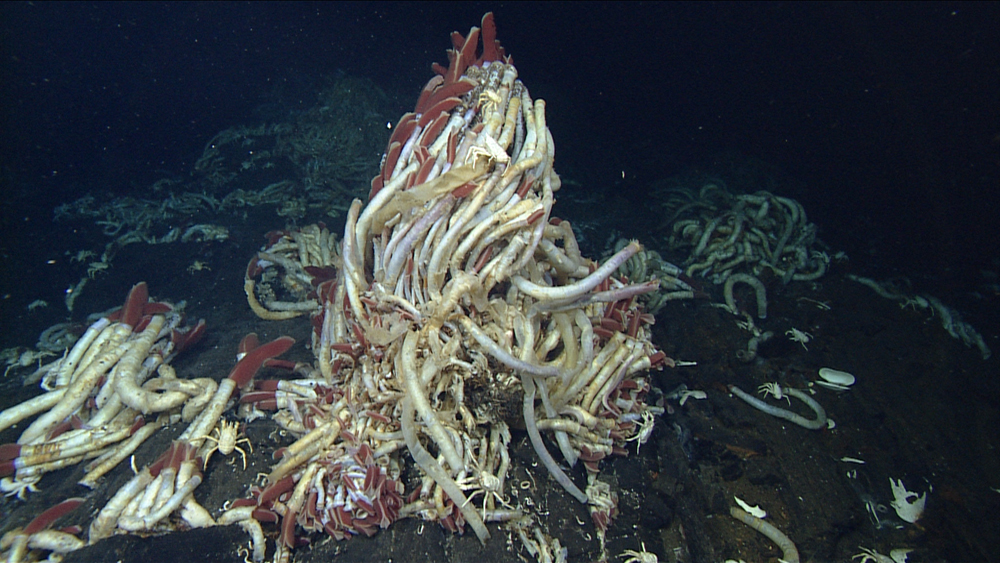

Superheated water — at temperatures of more than 750 degrees Fahrenheit (400 degrees Celsius) — spews from the vents. An entire ecosystem clings to the chimneylike columns, with worms and many other species consuming each other and the mineral-laden hydrothermal fluids. Exploring the deep-sea vents helps scientists determine the upper temperature limits for life.

The fleshy pink Pompeii worm (Alvinella pompejana) is one of the most extreme of the deep-sea creatures, perching its long, bristly tubes right next to the shimmering vent fluids. Earlier research had pegged the Pompeii worm's comfort zone as high as 140 F (60 C), far beyond that of other animals. But genetic and protein studies showed the worm's tissues would unravel at such high temperatures, just like raw eggs change when cooked. [Life at the Hydrothermal Seep (Video)]

First worms alive on ship

Solving the riddle was tricky because until now, Pompeii worms always died when brought to the surface. "The hottest animal on the planet, but the most difficult to study, summarizes the Alvinella enigma," said Bruce Shillito, a marine biologist at the University Pierre and Marie Curie in France.

So researchers from the university built a special pressure chamber for the worms to travel to the surface, to recreate the intense pressures at deep ocean vents. The team then tested heat extremes on the worms, looking at survival and how much stress the different temperatures caused. All of the experiments took place inside a high-pressure aquarium aboard a research ship.

The hydrothermal worms, from the East Pacific Rise,were given two heat tests. Each lasted two hours. The first ramped up from 86 to 108 degrees F (30 to 42 C) and the second from 122 to 131 F (50 to 55 C). The scientists discovered that the Pompeii worms survived the lower temperatures with no apparent tissue damage and little heat stress. But within 10 minutes of the hotter test, the worms crawled out of their tubes — an unnatural behavior — and by the end of the test, all 18 worms were dead.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Hot, hot, not

"Our study concludes that 50 degrees Celsius cannot be tolerated permanently by Alvinella," Shillito told LiveScience in an email interview.

"This doesn't mean it cannot 'adventure out' in higher temperatures, maybe 60 degrees Celsius, but then it would not be permanent. A bit like you and I, who can stick our finger under a tap with very hot water, but only for a few seconds. This same water would certainly kill us if we had a bath," Shillito said.

The temperature results match up with experiments on related hydrothermal worm species taken from other deep-sea vents, said Ray Lee, a marine biologist at Washington State University who was not involved in the study. However, Lee said there could be other, as yet unknown factors that help Pompeii worms survive hotter temperatures in their deep-sea home. The handling and chemistry changes during the trip to the surface could also affect how the worms respond to the tests, he said.

"It's like you're taking them from outer space and putting them on a shipboard lab," Lee said. "The major advance is that they have eliminated the decompression factor, and that's one of the hardest things to do."

Though the tests mean Pompeii worms like their homes a little cooler than thought, the creatures are still one of the most heat-tolerant animals on the planet. Shillito and his colleagues now plan to examine the worm's tissues and genes to understand how the animals thrive at the edge of hydrothermal vents.

Email Becky Oskin or follow her @beckyoskin. Follow us @livescience, Facebook & Google+. Original article on LiveScience.com.