High-Fat Diet May Increase Alzheimer's Risk

Diets high in saturated fat and sugar may increase the risk of Alzheimer's disease, and a new study may explain why.

In the study, participants who ate a diet high in saturated fat (including lots of beef and bacon) and "high glycemic index" foods (such as white rice and white bread) had an increase in levels of a protein called amyloid-beta in their cerebral spinal fluid. Amyloid-beta is a key component of the brain plaques that are a hallmark of Alzheimer's. High glycemic index foods release sugar quickly into the bloodstream.

In contrast, participants who ate a diet low in saturated fat (including fish and chicken) and low in high glycemic index foods (such as whole grains) had a decrease in amyloid-beta in their cerebral spinal fluid.

While previous studies have found that poor diet, obesity and diabetes are linked with an increased risk of Alzheimer's disease, the new study is one of the first to try to explain why, on a biological level, this might occur.

"Diet is a very important factor in determining brain health," said study researcher Suzanne Craft, a professor of medicine at Wake Forest School of Medicine in Winston-Salem, N.C. "The types of food we eat, particular dietary patterns that happen over long periods of time, are likely to have a substantial impact on our brains to the point where they may either protect or increase your risk of developing late-life brain disease like Alzheimer's disease," Craft said.

However, the study was small and examined the effect of diet over a very short time period — just one month. More research is needed to know whether the increase in amyloid-beta seen in this study would really result in Alzheimer's disease.

In addition, it's not clear if changing their diet would be helpful for people who already have a genetic risk for Alzheimer's.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Brain health and diet

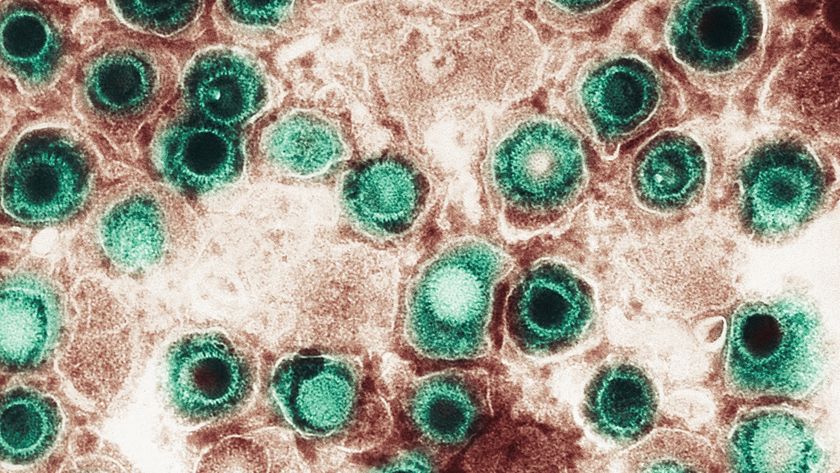

Amyloid-beta normally gets cleared from the brain, and problems with this process may increase the risk of Alzheimer's disease, Craft said.

One of the ways amyloid-beta is cleared is when it attaches to a protein called apolipoprotein E. When amyloid-beta is not attached to apolipoprotein E, it is in a "lipid-depleted" (LD) form that is less stable, and more likely to be toxic to the brain, Craft said.

The new study involved 47 adults in their late 60s, about half of whom had mild cognitive impairment, a condition in which people experience noticeable declines in their cognitive function, including memory and language problems.

Participants were randomly assigned to follow a high saturated fat, high glycemic index diet or a low saturated fat, low glycemic index diet for four weeks. Both groups ate the same number of total calories. Samples of cerebral spinal fluid were collected at the beginning and end of the study through a lumbar puncture.

Before participants started the diet, those with mild cognitive impairment had higher levels of LD amyloid-beta compared to those with normal cognition. Levels of LD amyloid-beta were particularly high among adults with mild cognitive impairment who also had a genetic risk factor for Alzheimer's (a mutation in a gene called ApoE4.)

After four weeks, those on the high saturated fat diet saw an increase in LD amyloid-beta levels, while those on the low saturated fat diet saw a decrease in LD amyloid-beta.

However, those with the ApoE4 mutation, who already had high levels of amyloid beta, did not get any better or worse when on either diet.

"It may be that the diet actually produces the same problem that the genetic risk factor produces," Craft said.

Good for the heart and brain?

A high saturated fat, high glycemic index diet, known to be bad for heart health, can lower levels of the hormone insulin in the brain. Insulin may be involved in the clearance of amyloid-beta from the brain, and thus play a role in Alzheimer's disease, Craft said.

In addition, high levels of "bad" cholesterol in the blood tend to be linked with low levels of "good" cholesterol in the brain, Craft said.

From this study, it's not clear whether changes in diet would eventually lead to less brain decay and better cognition, Dr. Deborah Blacker, of Massachusetts General Hospital, wrote in an editorial accompanying the study.

Still, the study "adds another small piece to the growing evidence that taking good care of your heart is probably good for your brain too," Blacker, who was not involved in the study, said.

The study is published today (June 17) in the journal JAMA Neurology.

Follow Rachael Rettner @RachaelRettner. Follow LiveScience @livescience, Facebook & Google+. Original article on LiveScience.com.

Rachael is a Live Science contributor, and was a former channel editor and senior writer for Live Science between 2010 and 2022. She has a master's degree in journalism from New York University's Science, Health and Environmental Reporting Program. She also holds a B.S. in molecular biology and an M.S. in biology from the University of California, San Diego. Her work has appeared in Scienceline, The Washington Post and Scientific American.