'Lost' Medieval City Discovered Beneath Cambodian Jungle

A lost city known only from inscriptions that existed some 1,200 years ago near Angkor in what is now Cambodia has been uncovered using airborne laser scanning.

The previously undocumented cityscape, called Mahendraparvata, is hidden beneath a dense forest on the holy mountain Phnom Kulen, which means "Mountain of the Lychees."

The cityscape came into clear view, along with a vast expanse of ancient urban spaces that made up Greater Angkor, the large area where one of the largest religious monuments ever constructed — Angkor Wat, meaning "temple city" — was built between A.D. 1113 and 1150. [See Images of Angkor Wat, New Temple City]

Traces of temples

In a series of archaeological mapping projects, scientists had previously used remote sensing to map subtle traces of Angkor. Even so, dense vegetation now veils much of the complex, impenetrable to conventional remote-sensing techniques, the researchers noted.

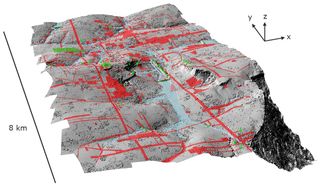

In the new study, led by the Archaeology and Development Foundation's (ADF) Phnom Kulen program, the team relied on airborne laser scanning, or LiDAR (light detection and ranging), to survey about 140 square miles (363 square kilometers) in northwestern Cambodia in 2012.

"LiDAR provides an unparalleled ability to penetrate dense vegetation cover and map archaeological remains on the forest floor," the researchers wrote in an accepted manuscript submitted to the journal Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

The survey revealed, "with exceptional clarity," traces of planned urban spaces hidden beneath the dense forest surrounding the major temples of Angkor, they wrote. In addition, the researchers confirmed the existence of "a vast, low-density urban periphery stretching far beyond the major Angkorian temples."

This low-density urban area suggests that rather than Angkor Thom being the central, walled-in city that some have suggested, it is just part of a more dispersed city with a densely populated area at its center.

"It's the same sort of configuration as Los Angeles — so, a dense middle, but it consists of huge, sprawling suburbs connected by giant roads and canals in exactly the same way as the freeways link up Los Angeles," said Roland Fletcher, of the University of Sydney.

Lost medieval city

To the north of central Angkor, the LiDAR data revealed a previously unknown city hidden beneath the forest, its roadways, temples and other urban infrastructure, etched into the surface of the holy Phnom Kulen mountain. The newfound cityscape would have existed between the eighth and ninth centuries (well before Angkor Wat) and seems to correspond to Mahendraparvata, one of the first capitals of the Khmer Empire. Until now, Mahendraparvata was known only from written inscriptions dating to A.D. 802, the researchers said.

When the LiDAR data revealed the elevation beneath Phnom Kulen's dense vegetation, the researchers knew they had found something big.

"With this instrument — bang — all of a sudden, we saw an immediate picture of an entire city that no one knew existed, which is just remarkable," Damien Evans, director of the University of Sydney's archaeological research center in Cambodia, told Australia's The Age.

Weird landscape

The LiDAR also revealed an entirely new class of Angkorian architecture, Fletcher said.

To the south of the Angkor Wat complex and dating to the 12th century, "there is a set of absolutely unique, very strange features, which we call rectilinear coils," Fletcher told LiveScience. "They are like enormous embankments of sand with channels between them. They have no counterpart anywhere in Angkor; we've never seen the design of this sort before, and they've never been seen before in Angkorian architecture."

Fletcher thinks the embankments represent gardens, but their exact purpose remains unknown. The channels would have carried water to the various plants and trees growing in the gardens, he suggested.

The research also involved French archaeologist and ADF program director Jean-Baptiste Chevance, Christophe Pottier of the French School of the Far East (EFEO), and other scientists.

Follow Jeanna Bryner on Twitter and Google+. Follow us @livescience, Facebook & Google+. Original article on LiveScience.com.

Jeanna Bryner is managing editor of Scientific American. Previously she was editor in chief of Live Science and, prior to that, an editor at Scholastic's Science World magazine. Bryner has an English degree from Salisbury University, a master's degree in biogeochemistry and environmental sciences from the University of Maryland and a graduate science journalism degree from New York University. She has worked as a biologist in Florida, where she monitored wetlands and did field surveys for endangered species, including the gorgeous Florida Scrub Jay. She also received an ocean sciences journalism fellowship from the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution. She is a firm believer that science is for everyone and that just about everything can be viewed through the lens of science.

Most Popular