Fungal Meningitis Update: Infection Traveled Surprising Route

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

The fungus responsible for the meningitis outbreak of last year travels an unusual route through the human body — moving upward through the spinal fluid to reach the brain, then later invading the blood vessels, according to new research.

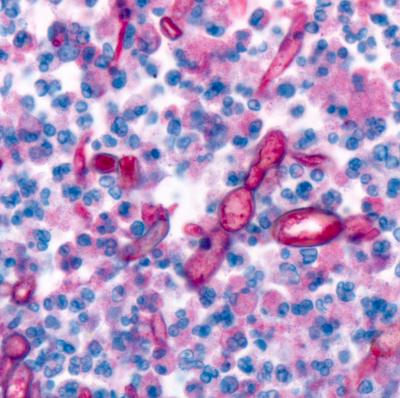

In efforts to unravel the outbreak of fungal infections due to steroid injections into the spine, which were contaminated by a fungus that rarely infects humans, investigators from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention examined tissue samples from 40 patients, including 16 fatal cases.

They found that the fungus, called Exserohilum rostratum, travels through the cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) upward along the spine, to reach the base of the brain where it causes meningitis. CSF is a bodily fluid that fills the space in the spine near where the contaminated drug was injected.

Exserohilum rostratum is a black mold commonly found in soil, but little is known about how it develops infections in human, as there had been very few cases reported before the outbreak of 2012.

In most infections, pathogens enter the blood immediately, and travel from one organ to the other. To the surprise of the CDC researchers, Exserohilum seemed to do this in reverse — infecting the brain first, then entering the blood.

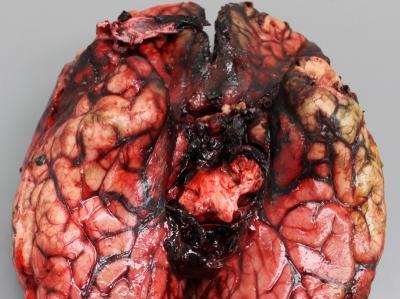

“Because of the site of injection, the fungi entered the CSF and settled down in the base of the brain, where it started invading the vessels,” said study researcher Dr. Sherif Zaki, chief of the Infectious Disease Pathology Branch at the CDC. At the stage where the fungus has reached the blood vessels, it doesn’t have a chance to travel farther, because the disease is fatal, he said.

Another unusual aspect of the infections the researchers found was that Exserohilum didn’t invade the neural tissue of the brain.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

“It was more confined to the meninges around the brain, whereas in a lot of fungal invasions, the fungi rapidly invade the brain tissue,” said Dr. Jana Ritter, another researcher in the study. The meninges are the membrane layers that cover the brain.

In conducting autopsies on people who had died from the fungal infection, the researchers saw extensive bleeding and tissue decay around the base of the brain, as well as inflammation and clots in the surrounding blood vessels, according to the report published today (June 26) in The American Journal of Pathology.

The CDC investigation follows the nationwide outbreak of fungal meningitis in 2012, in which 745 people were sickened, and 58 died. More than 13,000 people received injections of potentially contaminated steroid drugs made in a compounding pharmacy in Massachusetts. The injections were made to treat back or joint pain. [5 Meningitis Facts You Need to Know]

In the months following the outbreak health officials traced the contamination to more than 17,000 vials from three contaminated lots of a steroid drug prepared in a single compounding pharmacy, New England Compounding Center. The drug contained the fungus Exserohilum, which was also identified in the majority of patients.

Although all lots of contaminated vials were recalled, new patients are still being reported. The researchers are investigating how some people who received an injection last year may develop the infection months later.

“Looks like that the fungus can be injected and sit there at the injection site for up to several months. We don’t know yet how it manages to do that,” Ritter said.

Other mysteries also remain. The researchers saw a lack of immune response in some tissue that contained the fungus, which raised the question of “why, in some particular tissues, the fungus seems to be just sitting there, without having inflammatory cells around it,” Ritter said. The steroid shots putatively work to alleviate pain by suppressing the immune system, so it is tempting, the researchers said, to attribute this lack of immune response to the effects of steroids. However, studies of other fungal infections in patients whose immune system was compromised by other diseases would contradict this idea.

The new findings give more insights about how the fungus develops the infection, and may help clinicians to better decide which medications to use, and for how long. However, the CDC’s investigation continues, and future studies are needed to better understand human factors that contribute to infection and disease, as well as properties of Exserohilum, the researchers said.

Email Bahar Gholipour. Follow LiveScience @livescience, Facebook & Google+. Original article on Live Science.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus