How Earth Heals Itself After an Earthquake

For the first time, scientists have watched the Earth heal itself after an earthquake.

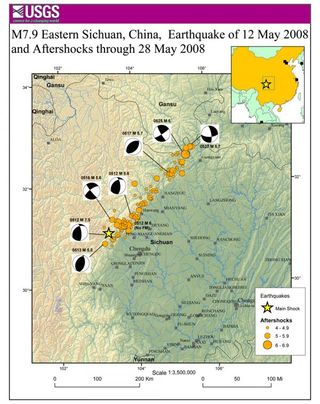

The process is similar to the body repairing a cut, researchers from China and the United States report today (June 27) in the journal Science. During an earthquake, the ground tears apart along a fault, leaving a jagged series of fractures. After China's devastating magnitude 7.9 Wenchuan earthquake in 2008, fluids filled the fractured fault, like blood gushing into a wound, the team found by drilling into the fault. Within two years — a blink of the eye in geologic time — the fault was speedily knitting itself back together, closing gaps through a combination of processes. But the gashes occasionally reopened when damaged by shaking from distant earthquakes, the study reports.

No one knows for sure how faults heal, and the observations from the Wenchuan drilling project offer more questions than answers. But the project's long-term monitoring of fractures opening and closing on a fault offers a series of fascinating puzzles for scientists to solve, said Chris Marone, a geophysicist at Penn State University who was not involved in the study.

"These are new observations. Unraveling exactly what's going on here could have serious implications for a lot of really important technical things," Marone said. Models based on the results could impact any place where water flows underground, such as in faults or aquifers or wells, he said. [7 Ways the Earth Changes in the Blink of an Eye]

Rapid response drilling

The Wenchuan project team tracked the healing process through a series of deep boreholes drilled through the fault. The study is part of an ongoing global effort to examine faults immediately after earthquakes, in hopes of checking the results of decades of laboratory experiments and computer modeling.

"We already know there are a lot of reasons real faults may not behave the way we think they do," said Emily Brodsky, a study co-author and geophysicist at the University of California, Santa Cruz. "If we're going to gain some actual new insights or go well beyond where our imaginations went before, we need the real deal," she said.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

The Chinese-sponsored Wenchuan earthquake Fault Scientific Drilling project began 178 days after the May 12, 2008, earthquake. The massive temblor killed more than 80,000 people. Five boreholes pierced through the messy fault zone, finding 0.4 inches (1 centimeter) of fresh fault gouge, a type of pulverized rock.

For 18 months, the team monitored the fault's permeability, a measure of how quickly water flows through the rock. Permeability is a stand-in for damage on the fault, Brodsky said — as the fault heals, the area should become less permeable to fluids. The experiment tracked the ebb and flow of fault fluids from tidal forces, the same tugs from the sun and moon that create ocean tides.

The researchers saw a steady decrease in permeability at the boreholes. As the gaps and fractures along the fault zone filled in with new minerals deposited by the fluids, or squeezed shut, the permeability drops, the researchers think.

The overall permeability drop was significantly faster than predicted by laboratory experiments, Brodsky told LiveScience's OurAmazingPlanet. The likely reason is rapid fault healing, but Brodsky said she doesn't have a good explanation for how that happens yet. "I don't know why it's faster," she said. "This sort of begs us to work out the process."

Remote triggering

But they did solve another puzzle: Six short-term jumps in the permeability, random events with no link to local aftershocks or equipment problems. The team eventually realized shaking from big but distant earthquakes broke open healed sections of the fault, Brodsky said. Some of the remote culprits include the March 2011 Japan earthquake and a magnitude-7.8 earthquake in Sumatra in April 2010.

"We expected to see some sort of healing effect, but we did not expect to see this re-damaging effect, so that was sort of a surprise," Brodsky said. "This interplay is a much more complicated process than we anticipated seeing."

Earthquakes on one fault are known to damage other nearby faults, and big earthquakes can trigger new temblors worldwide. But this is the first time effects of dynamic stress — the passing of seismic waves — have been seen on a fault with such detail.

"It really forces us to go back and put on our thinking caps about dynamic stresses," Marone said.

Email Becky Oskin or follow her @beckyoskin. Follow us @OAPlanet, Facebook & Google+. Original article on LiveScience's OurAmazingPlanet.

Most Popular