Climate Change May Stop Invasive Ant Cold

An aggressive ant species so vicious that in groups it can eat bird hatchlings alive may see its territory decline in the coming decades as climate change takes its toll on its habitats.

Pheidole megacephala, more popularly known as the big-headed ant, has been classified as one of the world's 100 most invasive species, found in every continent except Antarctica. A recent model, however, predicts global warming will slow the ants' march significantly by 2080.

"Ants, because they are a cold-blooded species, they are supposed to be very sensitive to small changes in temperature," said Cleo Bertelsmeier, a Ph.D. student at the University of Paris South. So Bertelsmeier used a model to look at how the species' distribution might change at the predicted levels of global warming.

The results show the ant populations and territory beginning to decline as soon as 2020, and then losing as much as one-fifth of their potential roaming territory by 2080.

Ant invaders

Invasive species are among the top threats to global biodiversity, Bertelsmeier notes in her research paper. As trade and tourism reach more far-flung areas, accidental and deliberate introductions of species into new areas become more prevalent. The native species then get crowded out and, in many cases, go extinct. [Alien Invaders: Destructive Invasive Species]

Because ants are small and colonial by nature, they are one of the best-equipped animals to take over a new area — making them one of the world's most invasive creatures, according to multiple studies.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

The big-headed ant is a particularly troublesome one that likely originated in Africa. .

"It has a lot of negative impacts on many other species — native ants, other invertebrates and even on birds," Bertelsmeier told LiveScience. She added that although big-headed ants often eat bird hatchlings when attacking in groups, they have an even larger impact on other ants and invertebrates.

But the ants' footprint extends even further. "They also eat seeds, so they can have an impact on plant populations and also agriculture," Bertelsmeier said. "They [cause] quite a crisis — in an invading area, some people are afraid of them."

To examine how the ants might be affected by climate change, Bertelsmeier and her colleagues created a model that took into account information from maps of the ants' potential range and climate scenarios based on reports from the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC).

Habitat decline

The range maps came from a New Zealand-based, publicly available database for ant distributions based on observational data sent in by students, private collectors, government agencies and biological researchers. Bertelsmeier's group further limited the data to remove instances where the ants were in greenhouses and other indoor areas.

Then, the researchers used a database called WorldClim to obtain climate information on which areas are most hospitable to ants both now and in the future. This project used data from the widely cited "IPCC Fourth Assessment Report: Climate Change 2007," which projected how the climate could change in the coming decades.

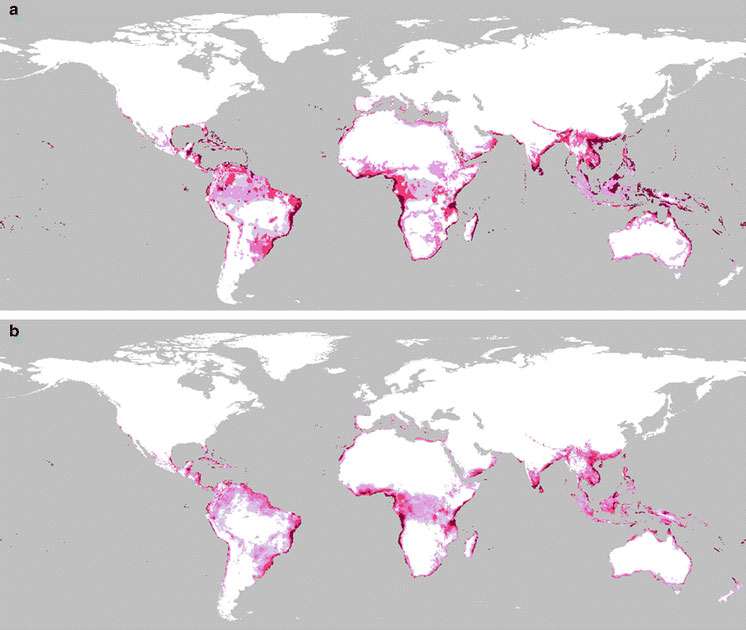

The models showed that currently, the ants have favorable climactic conditions in 18.5 percent of the global landmass; the best spots are in South America, Australasia and Africa. But this range will shrink by about one-fifth by 2080, according to the consensus model generated by the researchers.

Bertelsmeier said she hopes the current data on favorable habitats will assist in protecting native species from the invasive ant.

One key limitation in the data, though, is that the researchers aren't taking into account how the ants interact with other species when hey arrive in a new area, Bertelsmeier said, adding that she's currently researching that interaction.

The research paper appeared online in the journal Biological Invasions in December 2012, and was released in print form in mid-June.

Follow Elizabeth Howell @howellspace, or LiveScience @livescience, Facebook & Google+. Original article on LiveScience.

Elizabeth Howell was staff reporter at Space.com between 2022 and 2024 and a regular contributor to Live Science and Space.com between 2012 and 2022. Elizabeth's reporting includes multiple exclusives with the White House, speaking several times with the International Space Station, witnessing five human spaceflight launches on two continents, flying parabolic, working inside a spacesuit, and participating in a simulated Mars mission. Her latest book, "Why Am I Taller?" (ECW Press, 2022) is co-written with astronaut Dave Williams.