The oldest example of grave flowers has been discovered in Israel.

An ancient burial pit dating to nearly 14,000 years ago contained impressions from stems and flowers of aromatic plants such as mint and sage.

The new find "is the oldest example of putting flowers and fresh plants in the grave before burying the dead," said study co-author Dani Nadel, an archaeologist at the University of Haifa in Israel.

Though the exact purpose of these plants remains a mystery, the findings, detailed today (July 1) in the journal Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, shed light on some of the rituals used by one of the earliest human cultures living in fixed settlements.

Ancient tombs

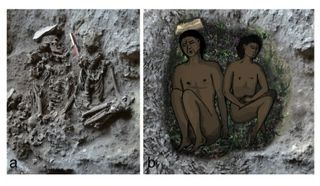

The burial pits, the first true gravesites in the world, were excavated nearly a half a century ago from Raqefet Cave in Mount Carmel, Israel. The people who made the tombs were part of a Natufian culture that flourished in the Near East beginning about 15,000 years ago. The region contains graves for hundreds of skeletons, including a burial of an ancient shaman woman. [In Photos: 14th-Century Black Death Grave Discovered]

The Natufians were the first people who transitioned from a nomadic, hunter-gathering lifestyle to a more sedentary one. They formed fixed settlements, built heavy furniture, domesticated the wolf, and began to experiment with domesticating wheat and barley, Nadel told LiveScience. Soon after, humans evolved the first villages, developed agriculture and went on to found some of the first empires in the world.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Past evidence suggested that humans only started using flowers in graves more recently. (A 35,000-year-old Neanderthal burial site called Shanidar Cave in Iraq contained pollen, but subsequent research revealed that it was likely that rodents living in the caves brought the pollen there, not humans.)

Though archaeologists first excavated Raqefet Cave years ago, Nadel and his colleagues did a more thorough excavation starting in 2004. The team found four burial sites, containing a total of 29 skeletons, which contained impressions from plant stems and flowers. The stems had a square cross-section, a relatively uncommon trait that is found in mint, sage and other aromatic plants from the region.

When they looked at the material under a scanning electron microscope, they found tiny phytoliths, or microscopic crystals made by plants.

The team concluded that the flowers were placed in the grave within a primitive plaster before the bodies were placed there. The bodies were buried between 13,700 and 11,700 years ago.

The new work is an example of "meticulous, scrupulous research," Anna Belfer-Cohen, an archaeologist at The Hebrew University of Jerusalem, wrote in an email. "Each Natufian site provides something new and exciting to our knowledge on those people about 15,000 years ago. Raqefet is rather a brilliant and an outstanding example."

Still, very little is known about why the graves were decorated with flowers or who the people were. In follow-up work, Nadel is hoping to do DNA analysis on the skeletons to see how or whether they are related.

And the larger question — why the Natufians evolved their sophisticated culture — is still a mystery, Belfer-Cohen wrote.

- Top 10 Weird Ways We Deal With the Dead

- In Photos: 'Alien' Skulls Reveal Odd, Ancient Tradition

- Top 10 Mysteries of the First Humans

Follow Tia Ghose on Twitter and Google+. Follow LiveScience @livescience, Facebook & Google+. Original article on LiveScience.com.

Tia is the managing editor and was previously a senior writer for Live Science. Her work has appeared in Scientific American, Wired.com and other outlets. She holds a master's degree in bioengineering from the University of Washington, a graduate certificate in science writing from UC Santa Cruz and a bachelor's degree in mechanical engineering from the University of Texas at Austin. Tia was part of a team at the Milwaukee Journal Sentinel that published the Empty Cradles series on preterm births, which won multiple awards, including the 2012 Casey Medal for Meritorious Journalism.

Most Popular