Scuba divers have discovered a primeval underwater forest off the coast of Alabama.

The Bald Cypress forest was buried under ocean sediments, protected in an oxygen-free environment for more than 50,000 years, but was likely uncovered by Hurricane Katrina in 2005, said Ben Raines, one of the first divers to explore the underwater forest and the executive director of the nonprofit Weeks Bay Foundation, which researches estuaries.

The forest contains trees so well-preserved that when they are cut, they still smell like fresh Cypress sap, Raines said.

The stumps of the Cypress trees span an area of at least 0.5 square miles (1.3 square kilometers), several miles from the coast of Mobile, Ala., and sit about 60 feet (18 meters) below the surface of the Gulf of Mexico.

Despite its discovery only recently, the underwater landscape has just a few years to be explored, before wood-burrowing marine animals destroy the ancient forest. [8 of the World's Most Endangered Places]

Closely guarded secret

Raines was talking with a friend who owned a dive shop about a year after Hurricane Katrina. The dive shop owner confided that a local fisherman had found a site teeming with fish and wildlife and suspected that something big was hidden below. The diver went down to explore and found a forest of trees, then told Raines about his stunning find.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

But because scuba divers often take artifacts from shipwrecks and other sites, the dive shop owner refused to disclose the location for many years, Raines said.

In 2012, the owner finally revealed the site's location after swearing Raines to secrecy. Raines then did his own dive and discovered a primeval Cypress swamp in pristine condition. The forest had become an artificial reef, attracting fish, crustaceans, sea anemones and other underwater life burrowing between the roots of dislodged stumps. [Images: Mysterious Underwater Stone Structure]

Some of the trees were truly massive, and many logs had fallen over before being covered by ocean sediment. Raines swam the length of the logs.

"Swimming around amidst these stumps and logs, you just feel like you're in this fairy world," Raines told LiveScience's OurAmazingPlanet.

Primeval forest

Raines reached out to several scientists to learn more about the forest. One of those scientists was Grant Harley, a dendrochronologist (someone who studies tree rings) at the University of Southern Mississippi.

Harley was intrigued, and together with geographer Kristine DeLong of Louisiana State University, set out to discover the site's secrets.

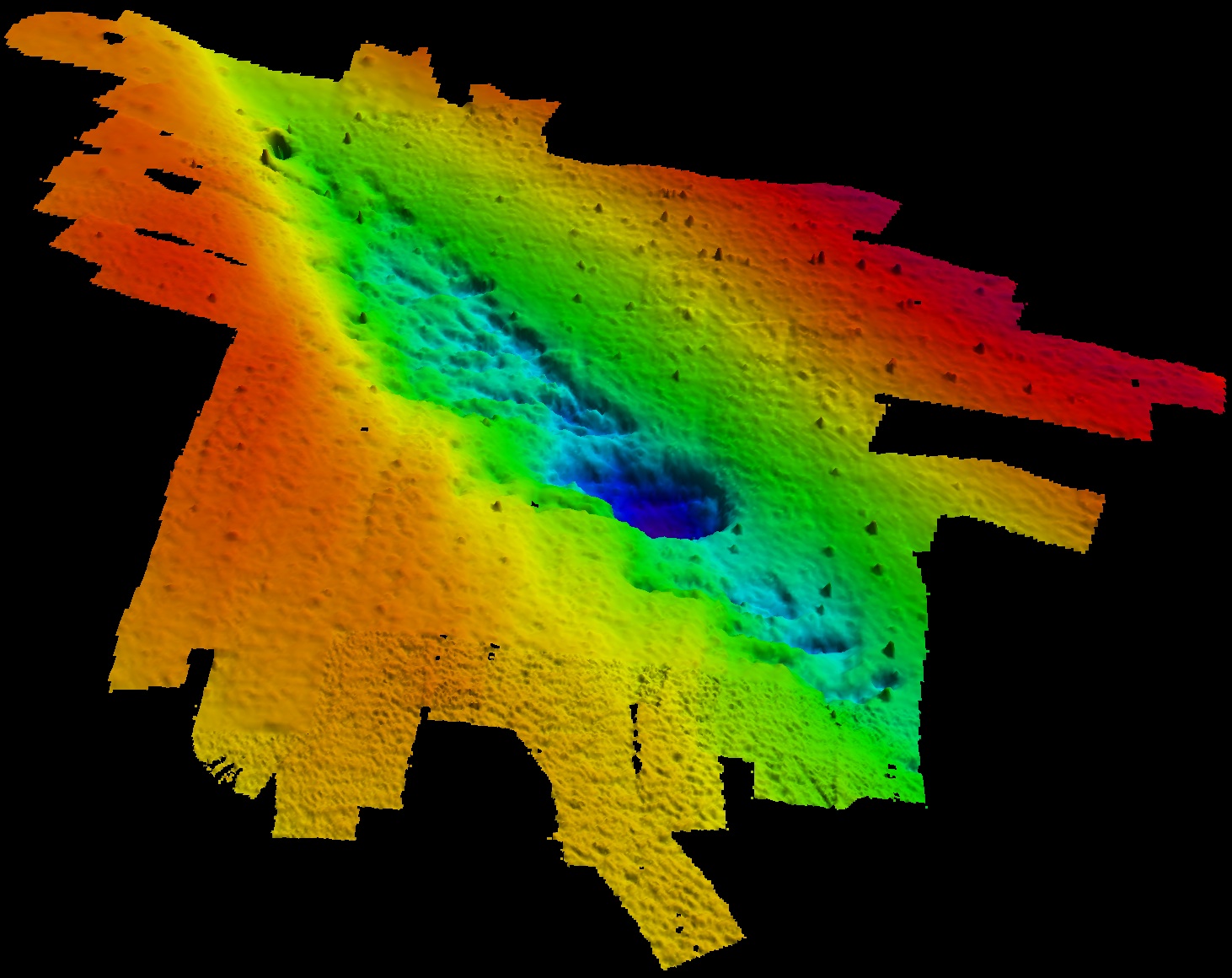

The research team created a sonar map of the area and analyzed two samples Raines took from trees. DeLong is planning her own dive at the site later this year. Because of the forest depth, scuba divers can only stay below for about 40 minutes before coming up.

Carbon isotopes (atoms of the same element that have different molecular weights) revealed that the trees were about 52,000 years old.

The trees' growth rings could reveal secrets about the climate of the Gulf of Mexico thousands of years ago, during a period known as the Wisconsin Glacial period, when sea levels were much lower than they are today. [World's Weirdest Geological Formations]

In addition, because Bald Cypress trees can live a thousand years, and there are so many of them, the trees could contain thousands of years of climate history for the region, Harley said.

"These stumps are so big, they're upwards of two meters in diameter — the size of trucks," Harley told OurAmazingPlanet. "They probably contain thousands of growth rings."

The team, which has not yet published their results in a peer-reviewed journal, is currently applying for grants to explore the site more thoroughly.

Harley estimates they have just two years.

"The longer this wood sits on the bottom of the ocean, the more marine organisms burrow into the wood, which can create hurdles when we are trying to get radiocarbon dates," Harley said. "It can really make the sample undatable, unusable."

Editor's Note: This article has been updated to correct the metric conversion of the area the forest spans. It is 1.3 square kilometers, not 0.8 kilometers.

Follow Tia Ghose on Twitter and Google+. Follow OurAmazingPlanet @OAPlanet, Facebook and Google+. Original article at LiveScience's OurAmazingPlanet.

Tia is the editor-in-chief (premium) and was formerly managing editor and senior writer for Live Science. Her work has appeared in Scientific American, Wired.com, Science News and other outlets. She holds a master's degree in bioengineering from the University of Washington, a graduate certificate in science writing from UC Santa Cruz and a bachelor's degree in mechanical engineering from the University of Texas at Austin. Tia was part of a team at the Milwaukee Journal Sentinel that published the Empty Cradles series on preterm births, which won multiple awards, including the 2012 Casey Medal for Meritorious Journalism.