Are the East Coast Heat Waves Related to Global Warming?

The heat wave gripping much of the East Coast and Midwest has people wondering: Could this scorching weather have any link to global warming?

Experts say it's hard to connect any single event with long-term trends.

Still, heat waves "are expected to happen more often in the future," said Jake Crouch, a scientist at the National Climatic Data Center. "As the average temperature increases, these types of events become more frequent."

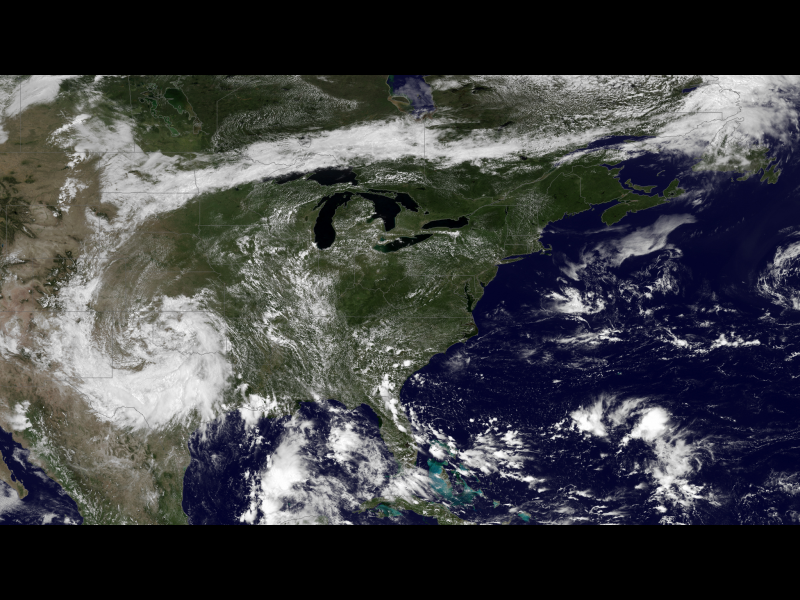

The current heat wave is somewhat unusual in that it is driven by a high-pressure system, also known as a Bermuda high, that has drifted farther west than usual, Crouch said. This mass of hot air is parked over the Great Lakes and eastern United States, rather than staying in its typical spot over the Southeast and Atlantic Ocean, he said.

But it's too early to say if this location change is related to a warmer climate, he added.

This week's East Coast heat wave differs from those of last summer, which were driven by a persistent mass of hot air called a heat dome that stayed in place for weeks over much of the central United States, Crouch said.

Last year's heat waves were also worsened by drought. Soil moisture can dissipate some heat as it takes up energy and evaporates; without water, it's easier for temperatures to climb, he added.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

However, a combination of rain and heat leads to high humidity, which is being seen in many places currently. And humidity can lead to higher nighttime temperatures, which are a major factor in deaths from heat, said Jeff Weber, a scientist with the University Corporation for Atmospheric Research in Boulder, Colo.

Hot nights don't allow people to cool down and get some relief, Weber said.

As the Earth continues to warm, heat waves are tending to last longer, Weber told LiveScience. The jet stream, which generally ferries weather patterns from west to east across North America, is driven by a difference in temperature between the cold Arctic and warm equator. Polar regions are heating faster than the equator is, which is leading to a weaker jet stream, Weber said.

That means weather systems, like high-pressure systems with high temperatures, tend to stay in place longer, he added.

Email Douglas Main or follow him on Twitter or Google+. Follow us @livescience, Facebook or Google+. Article originally on LiveScience.com.