The 20 Most Mysterious Shipwrecks Ever

Mysterious shipwrecks

For as long as humans have taken to the sea, there have been shipwrecks. UNESCO estimates that 3 million sunken ships litter ocean bottoms worldwide, many of which date back thousands of years. Some shipwrecks are well-documented or even deliberate — navies often deliberately scuttled ships to block entrances into ports or waterways, according to UNESCO. But others are veiled in mystery. Read on for a list of shipwrecks obscured not only by ocean waves, but by mysterious circumstances.

The loss of the Patriot

Aaron Burr, the third vice president of the United States, is most famous for killing former treasury secretary Alexander Hamilton in a duel. But Burr's life was marred by another death. His daughter, Theodosia, disappeared at sea at the age of 29, along with the rest of the passengers and crew on schooner called the Patriot.

The Patriot was traveling from Charleston, South Carolina, to New York City in December 1812 with Theodosia Burr aboard on a journey to visit her father. The last sighting of the ship was on Jan. 2, 1813, according to the blog North Carolina Shipwrecks. That night, a storm blew in. The ship was never heard from again.

Burr believed for the rest of his life that the ship sank and that his daughter was dead. But rumors flew about the ship's fate. Some said the ship had not gone down in bad weather, but had been captured by pirates, and the crew and passengers taken prisoner or murdered. For years, there were rumors that Theodosia Burr had survived, or washed ashore dead, or that her murderers had confessed. Perhaps one of the spookiest occurrences was the 1869 discovery of a painting of a well-heeled young woman in the home of a North Carolina woman whose family looted ships for a living. It had been found aboard an abandoned vessel that had drifted ashore at Nags Head on the Outer Banks, she told the doctor who treated her. Theodosia Burr was said to have been bringing a very similar portrait to New York as a gift for her father.

The Antikythera

In 1900, sponge divers came upon something strange on the ocean floor off the Greek isle Antikythera: a ship, strewn with what they were sure were rotting corpses. A second look proved that though lives may have been lost when the ship went down, none were still around to rot. The wreck was 2,000 years old, and the bodies the divers had seen were actually its load of bronze statuary.

The Antikythera shipwreck, a Roman vessel that went down sometime around 70 B.C., is still revealing new ancient treasures, including a bronze arm found in September 2017. Bones of unfortunate sailors have also been found amidst the wreckage, and researchers hope to extract ancient DNA from some of the more recent discoveries. But the most stunning find at the Antikythera site is the "Antikythera mechanism," a strange clockwork device in a wooden box that may have functioned as an analog computer. By spinning its gears, ancient users could map out the moon's phase and position, the position of the sun and predict 223 years of eclipses. The technology of the mechanism predates anything similar that has been found by at least 1,000 years.

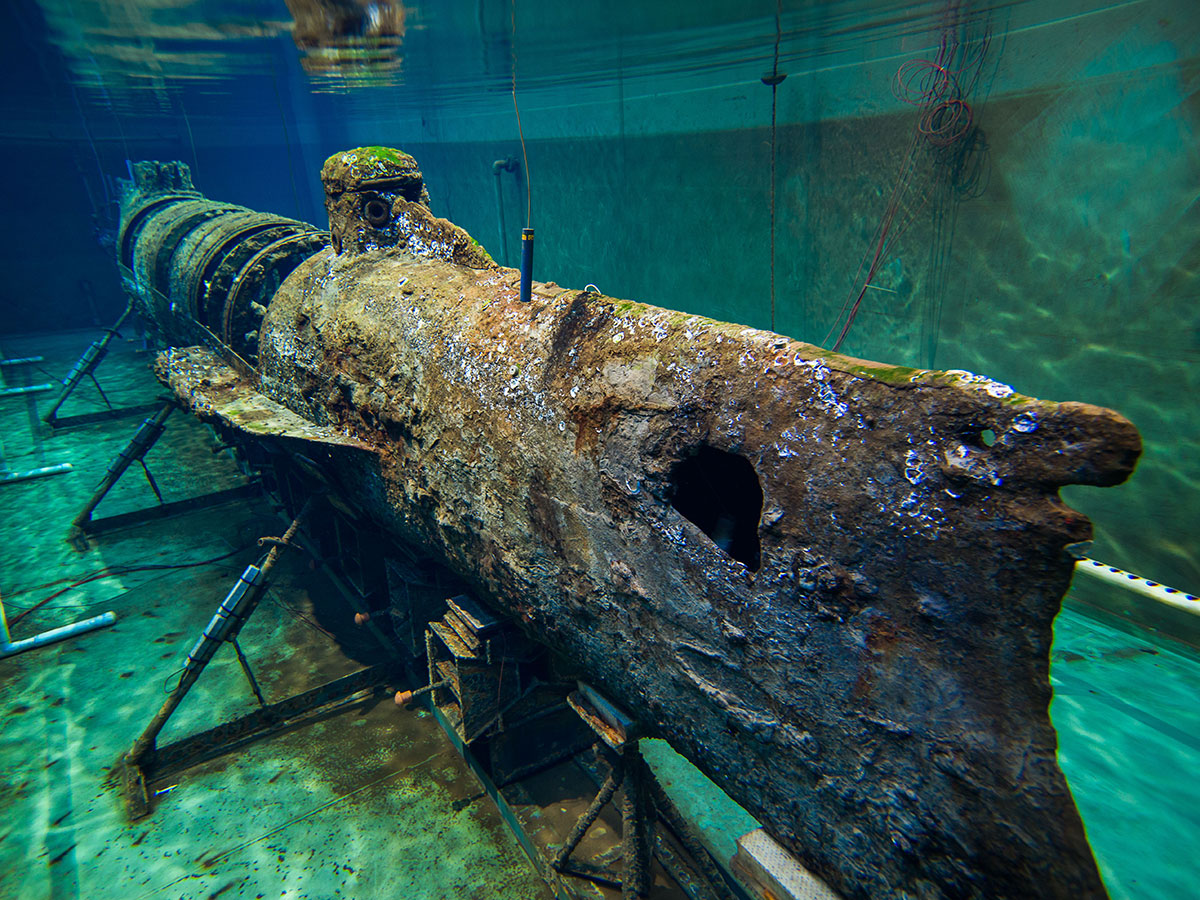

The Hunley

The Civil War submarine, the H.L. Hunley actually sank three times. First demonstrated in 1863, the ship is famous as one of the initial forays into developing combat submarines. She carried Confederate Navy men to Charleston Harbor, attempting to break a Union blockade that was strangling the city. On the very first mission, the Hunley sank at the dock when either the wake of a ship swamped it or tangled lines dragged it underwater. Five men died, according to Friends of the Hunley. The sub was recovered and launched again a few months later. Someone left a valve open and it sank, killing its entire 8-man crew.

The back-to-back disasters did not dissuade the Confederate Navy, though. The ship was found, modified and put back in service for a February 1864 mission in which it sunk the U.S.S. Housatonic, killing five. It would turn out to be a suicide mission for the Hunley's crew. The sub and all aboard were never heard from again — until 1995, when a team of wreck-hunters rediscovered it, with all eight crew members inside. In 2000, the wreck was raised. Still, no one knows what doomed the Hunley's final mission. She may have been crippled by her own torpedo, according to Friends of the Hunley, or trapped by ill-favored tides, leaving the crew to die of asphyxia when their air ran out. They may have been clipped by a Union rescue ship that never even noticed the collision, or perhaps someone managed a lucky shot that disabled the sub's captain and sent water pouring into the vessel.

The Griffin's many discoveries

In 2011, a couple of treasure-hunters were searching Lake Michigan for $200 million worth of gold that fell from a ferry crossing in the 1800s, at least according to local legend. What they found was perhaps less lucrative — but far weirder.

It was a shipwreck, covered with invasive zebra mussels. The treasure hunters thought it is the wreck of the Griffin, a ship built and lost by French explorer René-Robert Cavelier, Sieur de La Salle in 1679. La Salle was looking for the mouth of the Mississippi River when the Griffin went down. He'd gotten off the ship to pay off some of his debts, and his crew allegedly set sail in a storm and was never seen again. Since then, multiple people have thought they found the wreck.

Further investigations revealed the shipwreck found on the treasure hunt to be too large to be the Griffin. It was probably a late 19th-century or early 20th-century tugboat, according to state archaeologists. But another Griffin candidate has since emerged, in the form of a centuries-old wooden timber found at the bottom of the lake.

The World Trade Center Ship

After 9/11, during the rebuilding efforts at Ground Zero, construction workers stumbled upon something bizarre just south of where the Twin Towers used to stand. It was a wooden ship, mangled and skeletal. No one knew where it had come from.

It took four years, but archaeologists eventually used tree rings in the wood to reveal that the World Trade Center ship was built in the early 1770s, from old-growth wood of the same sort used to build Independence Hall in Philadelphia. But no one knows who the ship belonged to or how it ended up where it ended up. It may have sunk accidentally and inadvertently become part of the filled-in land that makes up parts of Lower Manhattan. Or it could have been deliberately scuttled as part of the foundation of that infill.

The very valuable San Jose

For 307 years, the Spanish galleon San Jose was missing — and with her, piles and piles of Spanish treasure meant to fuel an 18th-century war against the English.

The San Jose, carrying gold, silver and emeralds from Spain's colonial holdings in South America, went down in battle with four English ships in 1708. The fiery conflagration and subsequent sinking took 600 lives, though no one knows exactly why the San Jose exploded. It may have been that her powder room caught fire, or she simply may have succumbed to the power of the English bombardment. Whatever the case, the ship was rediscovered in December 2015. Disputes over its ownership have delayed its salvage and the discovery of whatever treasure might still be aboard. In June 2017, the Colombian government announced it was launching a public-private partnership to salvage the vessel, despite continuing legal claims by a private firm that claims to have found the ship and the modern-day Spanish government. The new mystery of the San Jose, it seems, is who owns it.

Nameless Ship

Sometime in the early to middle 1800s, a copper-plated wooden vessel sank 200 miles (321 kilometers) off the coast into the waters of the Gulf of Mexico. In 2011, a seafloor survey by oil giant Shell noticed a blip in a sonar survey. The National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) launched a mission to investigate, and, in 2012, discovered the rotting hull, a ship's stove and a variety of ceramic plates and glass bottles. National Geographic reported that later visits to the wreck revealed muskets, cannons and eyeglasses. The wreck could be anything from a passenger vessel to a pirate ship, the magazine reported.

The Mary Rose

The Mary Rose was a warship of King Henry VIII of England, built not long after Henry ascended the throne in 1509. She would participate in several skirmishes against the French early in her career, only to be kept in storage when the fighting died down. In the 1545, amid Henry VIII's quarrels with the Pope over his serial marriages and increasingly strained diplomatic relationships with monarchs on continental Europe, France attempted an invasion of England at Portsmouth. The Mary Rose was involved in the ensuing battle. At some point amid the cannon bombardment, she went down, taking more than 300 crewmen to their deaths. No one knows exactly why the warship sank, according to the museum dedicated to her memory. A recent retrofit may have left her too heavy to withstand an unlucky wind that caught her as she was turning. She may have been overloaded. Or perhaps a French cannonball hit her hull, swamping her. Even the rediscovery of the wreck and raising the Mary Rose from the seabed in 1982 hasn't answered this question.

Perfect Preservation

When geologists surveying the Black Sea stumbled across 40 centuries-old shipwrecks scattered around the bottom in 2016, it was a total surprise. Many of the ships looked as if they went down yesterday, despite the fact some sank during the days of the Byzantine Empire (330 to 1452). That's because the Black Sea's environment is unusual. Its lower water layers are salty influx from the Mediterranean, above which freshwater flowing in from the land floats gently. The lower salty layers are low in oxygen, meaning that wood-eating microbes can't survive down deep. This results in absurdly pristine shipwrecks.

Researchers used an ROV to investigate the Black Sea wrecks and photograph them, but their identities are lost to time.

A Twice-Lost Wreck

In 1850, the Jenny Lind was carrying 28 souls, including three children, from Melbourne to Singapore when it ran aground on a reef and sank. All crew and passengers survived by camping out on a spit of sand, building a boat salvaged from the Jenny Lind's wreckage and sailing 370 miles (600 km) in it to the Australian mainland.

The remains of the Jenny Lind remained visible on the reef until at least 1987, but in June 2017, maritime archaeologists reported that the ocean had beaten away at the wreck until nothing remained.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Stephanie Pappas is a contributing writer for Live Science, covering topics ranging from geoscience to archaeology to the human brain and behavior. She was previously a senior writer for Live Science but is now a freelancer based in Denver, Colorado, and regularly contributes to Scientific American and The Monitor, the monthly magazine of the American Psychological Association. Stephanie received a bachelor's degree in psychology from the University of South Carolina and a graduate certificate in science communication from the University of California, Santa Cruz.

Why is yawning contagious?

Scientific consensus shows race is a human invention, not biological reality