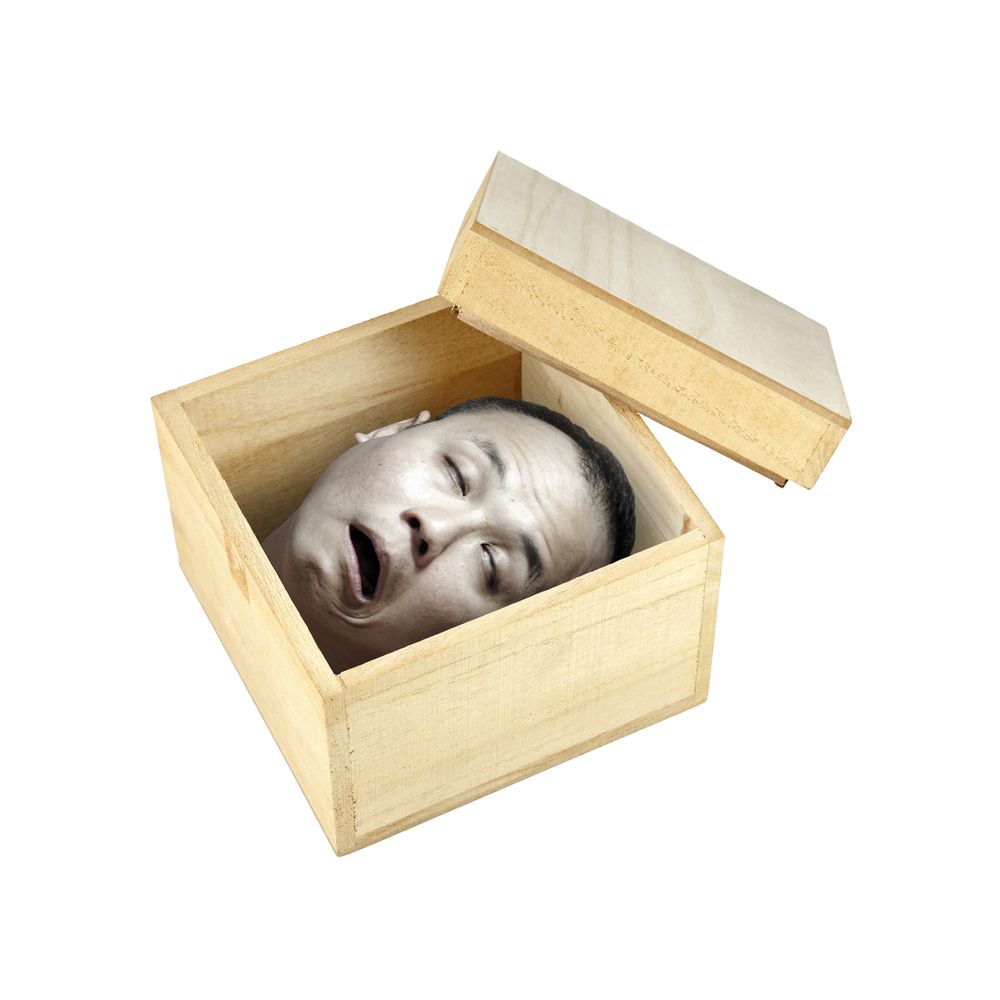

Can a Severed Head Live On?

Centuries-old tales have described severed heads that seemed to live on for a few seconds — blinking, changing expressions, even attempting to speak.

During the French Revolution, an executioner reportedly held the severed head of Charlotte Corday (who assassinated politician Jean-Paul Marat) aloft and smacked its cheek. Witnesses claimed Corday's eyes looked at the executioner, and an unmistakable expression of disgust came over her face.

More recently, in 1989, an Army veteran told of seeing a friend decapitated in a car crash. According to the story, the severed head showed emotions of shock, followed by terror and grief, its eyes glancing back at its separated body.

Compelling (and gruesome) as these stories may be, many physicians would call this possibility highly unlikely. At the moment of decapitation, the brain would suffer a massive drop in blood pressure. Rapidly losing blood and oxygen, the brain would likely go into coma, even if death took a few seconds.

Recent animal studies, however, lend some credence to those chilling stories.

In 2011, Dutch scientists hooked an EEG (electroencephalography) machine to the brains of mice fated to decapitation. The results showed continued electrical activity in the severed brains, remaining at frequencies indicating conscious activity for nearly four seconds. Studies in other small mammals suggest even longer periods.

If true in humans, those few seconds would provide enough time for a strange and terrifying experience: count off four seconds ("one Mississippi…"), and notice how much of your surroundings you can register.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

But anecdotes of severed heads trying to speak are likely just descriptions of bodily reflex actions. Indeed, severed limbs can twitch from muscle reflexes, and a subconscious, reflexive portion of the brain called the extrapyramidal system produces some expressions. This brain region causes, for example, the unconscious expressions of fear, disgust and contempt shown by infants.

Follow Michael Dhar @mid1980. Follow LiveScience @livescience. We're also on Facebook & Google+.

Michael Dhar is a science editor and writer based in Chicago. He has an MS in bioinformatics from NYU Tandon School of Engineering, an MA in English literature from Columbia University and a BA in English from the University of Iowa. He has written about health and science for Live Science, Scientific American, Space.com, The Fix, Earth.com and others and has edited for the American Medical Association and other organizations.

Most Popular