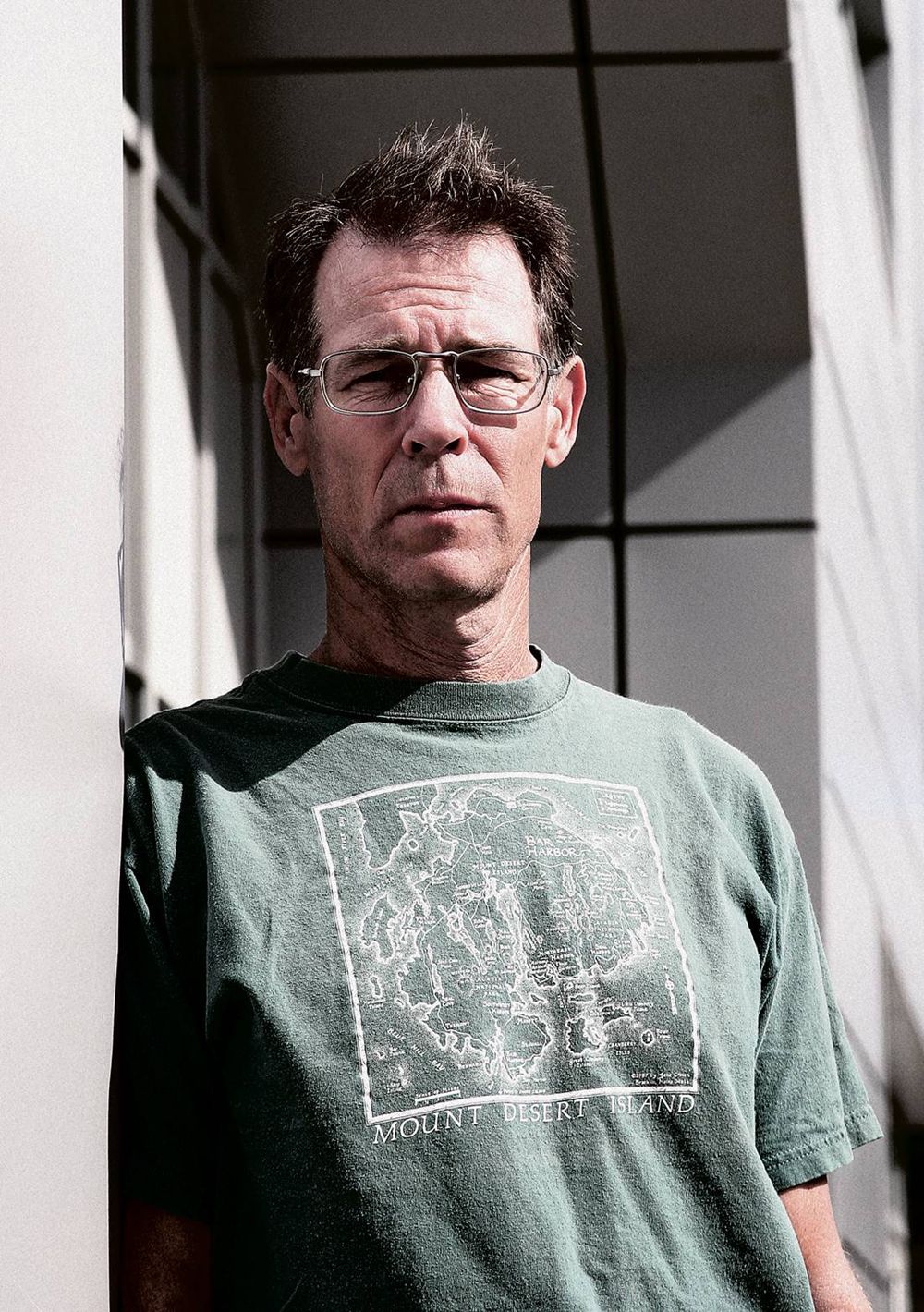

Looking 32,000 Years into the Past: Q&A With Author Kim Stanley Robinson

Thirty-two thousand years ago, the Earth would have been unrecognizable. The planet was in the throes of an Ice Age, now-extinct beasts roamed freely and Neanderthals may have lived alongside modern humans.

Science fiction writer Kim Stanley Robinson imagines this long-past world in his newest book, "Shaman," due out Sept. 3 from Orbit Books. The book follows the life of an apprentice shaman named Loon and a group of modern humans who painted the Chauvet Cave in southern France.

LiveScience recently caught up with Robinson about his inspiration, the extensive research he did for the novel, and the unique vocabulary he developed while writing. [Photos: Europe's Oldest Rock Art]

LiveScience: What kind of research did you do when writing "Shaman?"

Kim Stanley Robinson: Mostly, [I read] the relevant materials. There was also that Werner Herzog movie, "Cave of Forgotten Dreams." I got the DVD of when it became available, because it's that very cave that I'm writing about. I have an archaeologist friend who lives across the street who read the manuscript and friends at [the University of California], Davis connected me up with an anthropologist that works with preliterate cultures in New Guinea highlands. Also, my own snow-camping experiences just [gave me the] direct experience of being out in the snow with camping gear only. That was a big help. It comes down mostly to reading the relevant scientific literature and also other prehistoric novels that existed before mine.

LS: What kind of prehistoric novels did you read? Was the "Earth's Children" book series by Jean M. Auel one of them?

K.S.R.: I only looked a couple of pages and decided: "No, that's not really what I'm up for." There's a good novel by Elizabeth Marshall Thomas called "Reindeer Moon," and she grew up with what they used to call the bush people in South Africa as a girl, so she really knew preliterate cultures. William Golding's famous "The Inheritors" about the Neanderthals, that's a good one ... It was nice because the novels that I admire the most were not exactly my people or my period, but they gave me ideas.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

LS: Does this book have a place in your science fiction work?

K.S.R.: It has been part of the project all along for me — this science fictional project of what is humanity. What are we? What can we expect to become? How do we use technology? Is there a utopian future possible for us? In all of these questions, it becomes really important [to understand] how we evolved to what we are now and what we were when we were living the life that grew us as human beings in the evolutionary sense.

LS: What got you interested in this part of human history?

K.S.R.: I've been interested a super-long time and one of the triggers was the discovery of the iceman [dubbed Ötzi] in the glacier between Italy and Austria in '91. He was frozen with all of his gear. When I saw the photos and descriptions of his gear, I realized it was almost the same as my backpacking gear, but instead of being made of nylon and aluminum, it was made of cloth and straw and wood and leather. Most of the great ... paleolithic technology has all rotted away and disappeared on us, because thousands of years is long enough for organic material to disappear. I got interested at that point and that combined with the sociobology and the various science fictional interests that I had. [[Mummy Melodrama: Top 9 Secrets About Ötzi the Iceman]

LS: Why did you choose Chauvet Cave and the people who painted it as the backdrop for your story?

K.S.R.: The Chauvet Cave — that discovery was, like, 1995, and coffee table books appeared about 1999. The Herzog movie was in 2011 or 2010 and when I decided to do the people who painted that cave, it clarified a lot of things. It meant it was south France, it meant it was 32,000 years ago, it meant it was full-on Ice Age, and that the Neanderthals were still alive, some of them at least. It gave me my focus.

I became convinced that they probably were living as comfortably as possible, given the state of their knowledge about medicine and the universe. It became really interesting to think about how they didn't have writing, that this is a crucial technology that actually changes consciousness. Without it they were different from us in terms of how they transmitted their information from one generation to the next. It would become really important to teach master [to] apprentice. It would be really important to memorize things, to have a really talking culture so that their language would be Shakespearean — a very sophisticated talking culture, because they didn't have writing.

LS: How did you develop the unique vocabulary you used in the book?

K.S.R.: Once I realized that the narrator had to be talking and not writing, that made a huge difference. Then I had to think about words. I had to think about every word … I realized that as a normal writer, one of my most common phrases to start a sentence would be "in fact." The word fact began to look wrong. They didn't have facts. That's a modern concept … I couldn't use all kinds of words. I tried to examine every word ... I did develop a different vocabulary for all of the words for sexual parts. That was because the English language words are all heavily weighted by Judeo-Christian or modern pruderies or concerns. They all had baggage. I went back to Basque and Proto-Indo-European and I used real words. I just used real words from their time. What we're finding is that Basque is amazingly old, Proto-Indo-European is amazingly old ... There are about 100 words that linguists now have determined are probably as old as 15,000 years old that never changed like "mama" and "aye." I've been getting a fair amount of incredulity and a little bit of objection to having my characters say "mama mia," but it turns out that both of those words are outrageously ancient … There were lots of language games I had to play.

LS: Was the development of this kind of vocabulary a unique problem in this novel?

K.S.R.: I'm always really interested in the vocabulary that the novel affords me. The subject matter of my science fiction books will often give me the need for a scientific vocabulary or a philosophical vocabulary. I like to have these words appear in my novels and have the novels define them so that people aren't thrown out, but actually have their vocabularies expanded, because the book itself explains them. You can look these words up. I don't think I ever make up a word. I know that happens sometimes in science fiction, but I don't do it. [See Photos of Amazing Caves Around the World]

LS: Did you speculate at all or was all of your information pulled from archaeological and anthropological sources?

K.S.R.: I did think about what [the characters] would have that just wouldn't survive, [things that] archaeologists just can't speak to, but I think would have happened. One of them was essentially the proto-fireworks. If you're looking at a fire every night — and they were — sometimes there would be a blue flame or a green flame or a purple flame that would burst out that they would track down what made that color flame. They would find the minerals involved or the rotted wood, and they would collect it because it would be like their TV. It would be a way to entertain themselves at the festivals. The whole festival scene, I'm pretty sure they must have had such things, but there's no archaeological evidence.

LS: Have you visited the Chauvet Cave?

K.S.R.: No, I've never been to a painted cave, and I'm really looking forward to it when it happens. It's going to be a kind of emotional experience for me. I went into some of the California caves and also in a big one down in New Mexico a long time ago, 10 or 15 years ago. For this book, I went to some of the little marble caves in the Sierras just to see what cave-ness was like. In almost all the cave tours that you take, they turn the lights off and they have it be super-black. When that happened, I thought, god, I have to use that. It's kind of startling how black it is.

Originally published on LiveScience.