'Lost extinction,' uncovered for the first time, claimed more than 60% of Africa's primates

The extinction snuffed out more than half of the species in five mammal groups.

About 34 million years ago, a "lost extinction" in Africa wiped out the majority of primates, rodents and carnivores that preyed on the two groups. Species vanished in a slow-motion wave that spanned millions of years and yet went undetected by scientists — until now.

This previously unseen extinction bridges two geologic epochs: the Eocene (55.8 million to 33.9 million years ago) and the Oligocene (33.9 million to 23 million years ago). When the Eocene's greenhouse climate began shifting toward the icehouse temperatures that marked the Oligocene, sea levels dropped, the Antarctic ice sheet grew, and approximately two-thirds of all animal species in Europe and Asia went extinct.

Related: Wipeout: History's most mysterious extinctions

However, researchers thought that life in Africa had escaped this fate, and that animals there were shielded from the worst impacts of a cooling climate by their nearness to the equator. A spotty African fossil record from that period offered scientists few clues about what really happened to the continent's animal life as Earth cooled; a new look at animal lineages recently showed that climate change at the Eocene's end took a devastating toll on African mammal life, too.

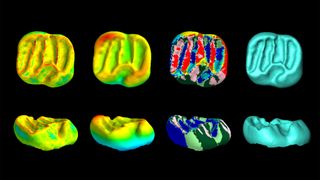

Using hundreds of fossils spanning tens of millions of years — from the middle of the Eocene into the Oligocene — scientists reconstructed evolutionary timelines in family trees across five African mammal groups. The researchers focused their attention on two groups of primates, two rodent groups and one group of extinct carnivores known as hyaenadonts ("hyena teeth") that preyed upon rodents and primates, they reported in a new study.

"In Africa, we just don't have the density of the fossil record that you see on other landmasses," said study co-author Erik Seiffert, professor and chair of the Department of Integrative Anatomical Sciences in the Keck School of Medicine at the University of Southern California, Los Angeles. "So, we had to figure out a way to extract as much information as we could, which is why we used this fairly novel approach," Seiffert told Live Science.

The authors used what fossils they had to track species diversity and loss over time in those animal groups. As they did, patterns began to emerge, showing that around 34 million years ago, a cooling Earth lopped off entire branches of those mammals' family trees. Species diversity didn't drop abruptly, as is often the case in global mass extinction events. Rather, the decline happened over millions of years, until 63% of the species in those mammal groups had disappeared.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

"Over the course of 4 million years, we see this gradual slow loss of all of the lineages that had been present in the late Eocene," Seiffert said. "The biggest trough of that lineage diversity curve really bottoms out at 30 million years ago, and then starts to pick back up around 28 million years ago."

When those groups began to diversify again, many of the new species had evolved new traits that weren't present in species that came before the extinctions, according to the study. For example, rodent and primate species that emerged during the Oligocene had different tooth shapes than their extinct cousins, hinting that these animals were adapted to survive in different ecosystems than their predecessors experienced.

"Extinction is interesting in that way," study co-author Matt Borths, curator of Duke Lemur Center Division of Fossil Primates, said in a statement. "It kills things, but it also opens up new ecological opportunities for the lineages that survive into this new world."

Was it global cooling that extinguished those African mammals? While that was probably a factor, other evidence from Africa and the Arabian peninsula from around 31 million years ago suggests that unusually active volcanoes may have posed another insurmountable challenge to their survival, Seiffert said.

"All this volcanic activity that would ultimately lead to the rising and development of the Ethiopian highlands, it started around 31 million years ago with some really dramatic volcanic super-eruptions," he said. "That part of eastern Africa was continually being altered by these volcanic events. If not necessarily causing extinctions, those constant changes to the environment may have been at least delaying diversification in some of these lineages."

The findings were published Oct. 7 in the journal Communications Biology.

Mindy Weisberger is an editor at Scholastic and a former Live Science channel editor and senior writer. She has reported on general science, covering climate change, paleontology, biology and space. Mindy studied film at Columbia University; prior to Live Science she produced, wrote and directed media for the American Museum of Natural History in New York City. Her videos about dinosaurs, astrophysics, biodiversity and evolution appear in museums and science centers worldwide, earning awards such as the CINE Golden Eagle and the Communicator Award of Excellence. Her writing has also appeared in Scientific American, The Washington Post and How It Works Magazine. Her book "Rise of the Zombie Bugs: The Surprising Science of Parasitic Mind Control" will be published in spring 2025 by Johns Hopkins University Press.