Why One Microbe Doesn't Age

Aging is an inevitable fact of life for most organisms, but one particular microbe has found a way to avoid getting older, at least in a sense, a new study finds.

Under favorable conditions, the microbe, a species of yeast called S. pombe, does not age the way other microbes do, the researchers said.

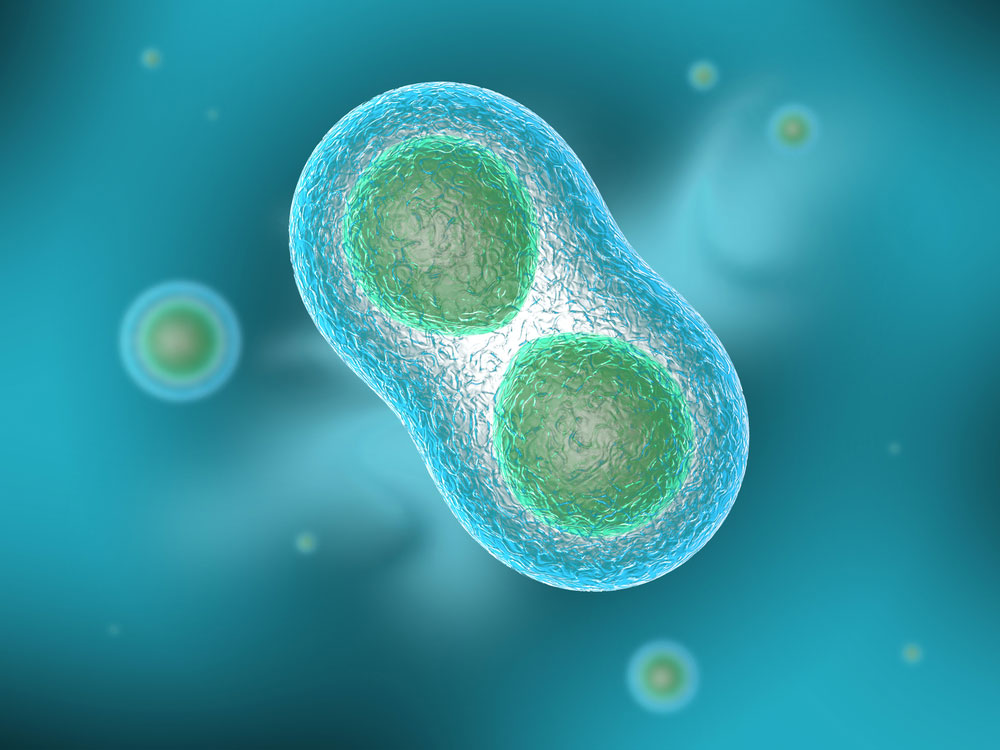

Typically, when single-celled organisms divide in half, one half acquires the majority of older, often damaged cell material, while the other half acquires mostly new cell material.

But in the new study, researchers found that under favorable, nonstressful growing conditions, S. pombe (a single-celled organism) divided in such a way that both halves acquired about equal parts of old cell material. "As both cells get only half of the damaged material, they are both younger than before," study researcher Iva Tolić-Nørrelykke, of the Max Planck Institute of Molecular Cell Biology and Genetics in Germany, said in a statement. [Living Forever: The Top 10 Immortals]

What's more, previous research has shown that when cells divide and continuously pass on old cell material, the cells that get the old material start to divide more slowly — a sign of aging. This has been seen in microorganisms such E. coli and the yeast S. cerevisiae.

But in the new study, S. pombe cells showed no increase in the time it took for them to divide, the researchers said.

That's not to say that S. pombe cells don't die. Some cells did die in the study, but the deaths occurred suddenly, as a result of a catastrophic failure of a cellular process, rather than aging, the researchers said.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

The researchers said they are not arguing that any given component of S. pombe cells are immortal. If a particular component of a cell is followed for a long enough time, the researchers believe the cell that harbors this component will eventually die. But "the probability of this death will be constant rather than increasing over time," the researchers wrote in the Sept. 12 issue of the journal Current Biology.

During unfavorable, stressful conditions, S. pombe cells distribute old cell material unevenly, and the cells that inherited the old material eventually died, the study found. Also, during stressful conditions, S. pombe showed an increase in division time.

Although there's no way to know for sure why the researchers did not detect aging in S. pombe under favorable conditions, one likely explanation is that the cellular damage is being repaired at the same rate that it's being formed, said Eric Stewart, a microbiologist at Northeastern University in Boston, who was not involved in the study.

But just because the study researchers did not detect aging in favorable conditions doesn't meant that it's not occurring. "They're trying to show the absence of something," in this case, aging, Stewart said. "Showing the absence of something is a nearly impossible challenge," he said.

S. pombe growth under favorable conditions could potentially serve as a model of nonaging cell types, such as cancer cells, the researchers said.

Follow Rachael Rettner @RachaelRettner. Follow LiveScience @livescience, Facebook & Google+. Original article on LiveScience.

Rachael is a Live Science contributor, and was a former channel editor and senior writer for Live Science between 2010 and 2022. She has a master's degree in journalism from New York University's Science, Health and Environmental Reporting Program. She also holds a B.S. in molecular biology and an M.S. in biology from the University of California, San Diego. Her work has appeared in Scienceline, The Washington Post and Scientific American.