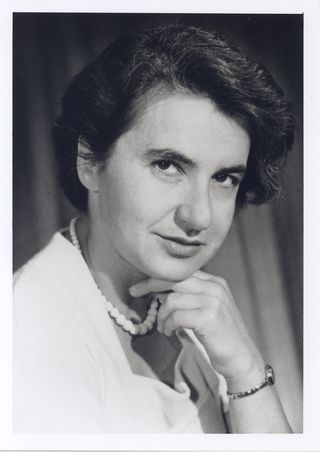

Rosalind Franklin: Biography & Discovery of DNA Structure

Many people recall that the structure of the DNA molecule has the shape of a double helix. Some may even recall the names of the scientists who won the 1962 Nobel Prize in Medicine for modeling the structure of the molecule, and explaining how the shape lends itself to replication. James Watson and Francis Crick shared the Nobel Prize with Maurice Wilkins, but many people feel that much of the credit for this world-shaking achievement should rightfully go to someone who was absent from that stage, a woman named Rosalind Franklin.

Rosalind Franklin was born July 25, 1920, and grew up in a well-known Jewish family in pre-World War II London, and was known in the family for being very clever and outspoken. Her parents sent her to St. Paul’s Girls’ School, a private school known for rigorous academics, including physics and chemistry. In an interview for PBS’ NOVA television episode titled "The Secret of Photo 51," two of her friends recalled memories of Franklin’s school days.

“She was best in science, best at maths, best in everything. She expected that if she undertook to do something, she would be in charge of it.” By the age of 15, over objections from her father, who thought she should go into social work; Franklin decided to become a scientist.

Franklin graduated from Newnham College at Cambridge in 1938 and took a job with the British Coal Utilization Research Association. She was determined to make a contribution to the war effort, and published several papers on the structures and uses of coal and graphite. Her work was used in development of the gas masks that helped keep British soldiers safer. Her work earned her a Ph.D. in Physical Chemistry awarded by Cambridge University in 1945.

In 1947, Franklin moved to Paris to take up a job at the Laboratoire Central working with Jacques Mering on perfecting the science of X-ray chromatography. By all accounts, she was very happy in Paris, easily earning the respect of her colleagues. She was known to enjoy doing the meticulous mathematical equations necessary to interpret data about atomic structure that was being revealed by the X-ray techniques. However, in 1951, she reluctantly decided it was necessary to move back to London to advance her scientific career.

Skirting a leftover bomb crater to enter the lab at King’s College in London, Franklin found she was expected to work with antiquated equipment in the basement of the building. She took charge of the lab with her customary efficiency, directing the graduate student, Raymond Gosling, in making needed refinements to the X-ray equipment.

She was annoyed when she discovered that she was expected to interrupt her work and leave the building for lunch every day. Women were not allowed in the College cafeteria. Nevertheless, she and Gosling were making progress in studying DNA when Maurice Wilkins, another senior scientist, returned from his vacation.

Wilkins was upset to learn that the female “assistant,” who he had expected would be working for him, was instead a formidable researcher in her own right. In this tense atmosphere, Franklin continued working to refine her X-ray images, using finer DNA fibers and arranging them differently for her chromatography, but she began to fear she had made a mistake in leaving Paris. Wilkins, also uncomfortable, began to spend more time at nearby Cavendish Laboratory with his friend Francis Crick. Crick and his partner, James Watson, were working on a model-based approach to trying to discover the structure of the DNA molecule.

Around this time, Franklin and Gosling made a startling discovery. There were two forms of DNA shown in the X-ray images, a dry “A” form and a wetter “B” form. Because each X-ray chromatograph had to be exposed for over 100 hours to form an image, and the drier “A” form seemed likelier to produce images in more detail, Franklin set aside the “B” form to study later. She noted that the “B” form images appeared to show a definite helical structure and that there were two clear strands visible in the image she labeled Photo 51 before she filed it away.

Around this time, Franklin attended a conference given at Cavendish to observe an early DNA model being proposed by Watson and Crick. She was quite critical of their work, feeling that they were basing their model solely on conjecture whereas her own work was based on solid evidence.

Her treatment of his friends widened the gap between her and Wilkins, leading to an even more strained relationship at King’s College. Franklin was so unhappy that people in the lab began to talk behind her back calling her the “Dark Lady.” In 1953, she decided to move to Birkbeck College to escape King’s. Somehow, during the move, Wilkins came to be in possession of Franklin’s notes and the files containing Photo 51. Wilkins removed the photo from her records without her knowledge or permission and took it to show his friends at Cavendish. [Related: 'Lost' Letters Reveal Twists in Discovery of Double Helix]

“My mouth fell open and my pulse began to race,” wrote Watson in his famous book, "The Double Helix." It was the one bit of information that he and Crick needed to complete an accurate model of the structure of DNA. Photo 51 was proof that DNA’s helical structure had two strands attached in the middle by the phosphate bases. They hurried to publish their findings in the journal Nature. The same issue of the journal published much shorter articles by Wilkins and Franklin, but placed them after the longer article by James Watson, seeming to imply that their work merely served to confirm the important discovery made by Watson and Crick rather than being integral to it.

Franklin, meanwhile, had moved on to Birkbeck. Part of the arrangement that allowed her to leave King’s was that she would not pursue any research on DNA, so she turned her talents to studying virus particles. Between 1953 and 1958, she made important discoveries about the tobacco mosaic virus and polio. The work done by Franklin and the other scientists at Birkbeck during this time laid the foundation of modern virology.

Franklin died on April 16, 1958, of ovarian cancer, possibly caused by her extensive exposure to radiation while doing X-ray crystallography work. Because the Nobel Prize can only be shared among three living scientists, Franklin’s work was barely mentioned when it was awarded to Watson, Crick and Wilkins in 1962. By the time "The Double Helix" was written in 1968, Franklin was portrayed almost as a villain in the book. Watson describes her as a “belligerent, emotional woman unable to interpret her own data.”

It is only in the past decade that Franklin’s contribution has been acknowledged and honored. Today there are many new facilities, scholarships and research grants especially those for women, being named in her honor.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.