Not Just CGI: The Incredible Tech of Horror-Movie Monsters

Editor's Note: In this weekly series, LiveScience explores how technology drives scientific exploration and discovery.

His eyes were black as night, his teeth jagged, his nostrils unnaturally large. It's said that when movie audiences first saw him, they fainted in fright.

Lon Chaney's 1925 portrayal of the Phantom of the Opera was spooky indeed — and an impressive testament to what the actor could do with greasepaint and a bit of thin wire to pull back his nostrils, mimicking the open nose of a skull. Today's special effects, however, require a bit more technical savvy. That's not just because audiences want to see more gore; high-definition cameras have also turned movie make-up into an art form requiring incredible attention to detail.

Computer-generated imagery might be replacing some of the shuffling zombies and rubber-suited monsters of yesteryear, but the technology of special effects isn't all in a central processing unit, according to Andrew Clement, the owner of Creative Character Engineering in Van Nuys, Calif. [Making Monsters: Images of Spooky Special Effects]

"People really like the tangibility of a practical effect. An actor will act different when he's got makeup on. I did the entire run of 'ER' from the pilot to the final episode and to have actors be able to actually hold a silicon baby or to be able to get into their elbows in a chest that's filled with fake organs, it's just different," Clement told LiveScience.

Keeping it real

Clement's shop has created a whole gallery of horrors, from burn-victim serial killer Freddie Kruger in "A Nightmare on Elm Street" to vampire victims in "Let Me In." His team uses emerging technologies, including 3D printing, to turn actors into monsters and rubber and silicon into aliens, corpses and more.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

"What we do is we steal materials from every discipline there is on the planet. … Medical, dental prosthetics, robotics, high-end mold-making, auto racing, robots, people who do remote control work, just anybody," said Clement.

To create body replicas or personalized movie makeup for actors, Clement and his team start by making a "livecast." This involves slathering their actor with a material that then hardens and can be peeled away, creating a body double. For decades, the industry used a material called alginate, a seaweed derivative, to create the casts, but it set slowly and didn't create the most precise casts, Clement said. SFX experts have since taken a page from the playbook of dentists, who use silicone to make casts of teeth. Silicone is far easier to manipulate than other options, Clement said, and it can be used to make features like Freddie Kruger's burnt skin that won't melt off the actor's face under harsh production lights. [The Psychology of America's Favorite Scary Monster]

The work requires an artist's eye as well as a technical touch. For one scene in "Let Me In," a murder victim needed to be hanging upside down from a tree. Flipping upside down completely changes the way gravity acts on a face, Clement said, so he and his team got creative: They had their actor get on an inversion table, a piece of equipment used to relieve back pain by turning a person upside down.

The team placed the silicon, waited for it to gel, and then, as it was still slightly soft, flipped their silicone-coated model at a 45-degree angle. The resulting cast captured the upside-down effect perfectly, Clement said.

"It didn't look correct when you looked at it right-side up, but when you looked at it upside down, it was quite convincing," he said.

Clement isn't the only special-effects expert who repurposes materials and techniques for the perfect onscreen look. Mark Coulier, the director of Coulier Creatures and winner of an Academy Award for his work on 2011's "The Iron Lady," was responsible for many of the effects seen in the "Harry Potter" films. One particular challenge was a scene in which Daniel Radcliffe, playing Harry, sprouted webbed fingers for an underwater swim. Prosthetic webbing couldn't stand up against the force of the water, Coulier said, and whole-handed gloves just looked weird and bulky.

"We ended up covering his whole arm with a woman's stocking and we stuck the stocking together between his fingers and painted silicone on," Coulier told LiveScience.

Printing monsters

The digital world has changed the world of practical effects — there are fewer opportunities now to build a life-sized animatronic T. rex, said Coulier and Clement. Computer graphics are simply cheaper for an effect of that scale.

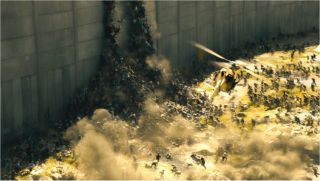

But the art of prosthetic makeup is still going strong. Even the heavily CGI spectacle of 2013's zombie-apocalypse film "World War Z" was underpinned by real-world makeup.

"We did close to 5,000 makeups on World War Z, because basically you've got these guys running down the street and there's a hundred of them and you may glimpse a makeup on one of them, so you have to do the hundred, really," Coulier said. His team's work is spotlighted late in the film when Brad Pitt gets up-close-and-personal with a lab full of zombie scientists. [The 10 Scariest Movies Ever]

Meanwhile, 3D printing has changed the way Clement does business. The effects' gurus can sculpt a monster head using a computer program, then make tweaks and print it out.

"It's an extremely fast way of sculpting and of doing concepts," Clement said. Concepts are the mock-ups shown to moviemakers as a sort of first draft of the effect. Instead of building them from scratch only to have to re-do them with filmmakers' fixes, Clement's team can now keep them digital-only until all the changes have been made.

"On Harry Potter, we had a big old giant spider we did for the last film and we had to build a smaller version of the same thing, so we had it scanned and 3D printed," Coulier said. He still prefers old-fashioned sculpting by hand much of the time, however.

"You get what I call happy accidents when you sculpt things physically with a clay material that just don't happen when you sculpt on the computer," he said.

High-definition film has created new challenges for effects' makers. It picks up "every pore," Clement said, as well as any minute difference between an actor's skin and the prosthetic silicon on their face.

"You have to go in and you have to subtly pull out the colors of either the skin or the appliance and sort of marry them together in this nice way," Clement said.

What can't be fixed in the physical world can often be smoothed out by digital technology. If production can't afford the finest wigs and makeup, Coulier said, they often can afford digital touch-ups to improve the look.

The future of film effects

Small changes in materials make a big difference for prosthetic effects. Slight improvements in materials and mold-making help to make big tasks, like making actors look older, easier. Coulier and his team worked on the upcoming biopic "Mandela: Long Walk to Freedom," which required them for the first time to apply a realistic aging look to dark skin.

"Each time you do these pieces and you put them on, you learn something else," Coulier said.

Clement expects 3D printing to feature more heavily in future films. As printers can handle more materials at once, he said, they may be able to print out an entire monster head, rather than printing out parts for assembly. Improved motion capture technology may also make animatronic characters more life-like.

No matter how advanced the tech, however, what really matters in the end is "good scripts," Coulier said.

"It doesn't matter if I have to age somebody or make a zombie or make a vampire or a deformed thing or make somebody young or more beautiful," he said. "It just matters if it's a good film in the end."

Follow Stephanie Pappas on Twitter and Google+. Follow us @livescience, Facebook & Google+. Original article on LiveScience.

Stephanie Pappas is a contributing writer for Live Science, covering topics ranging from geoscience to archaeology to the human brain and behavior. She was previously a senior writer for Live Science but is now a freelancer based in Denver, Colorado, and regularly contributes to Scientific American and The Monitor, the monthly magazine of the American Psychological Association. Stephanie received a bachelor's degree in psychology from the University of South Carolina and a graduate certificate in science communication from the University of California, Santa Cruz.

Most Popular