A new way of texturing surfaces could make for materials that are ultra-waterproof.

The new surface takes advantage of the fact that rougher, uneven textures cause water droplets to bounce off of them more quickly. And the less time water stays in contact with a surface, the drier that material stays.

The new method could be used for many applications, including waterproof clothing and sports gear, as well as anti-icing tech for airplane wings.

Previously, researchers thought that water droplets recoil fastest when they hit a surface in a perfect, symmetrical shape. But Kripa Varanasi, a mechanical engineer at MIT, and his colleagues, decided to take a look for themselves.

They used a high-speed camera to film water droplets as they bounced off a silicone wafer sprayed with a highly water-repellent coating. They found that droplets that hit the surface, then spread out symmetrically before recoiling actually spent more time in contact with the surface than those that hit unevenly.

So, the researchers created a new textured rough surface with small ridges that broke up the drops when they hit a hydrophobic, or water-repellent, surface. Those smaller drops then took less time spreading out on the surface before bouncing off of it.

But it turns out they weren't the first to discover this waterproofing strategy; nature had beaten them to it.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

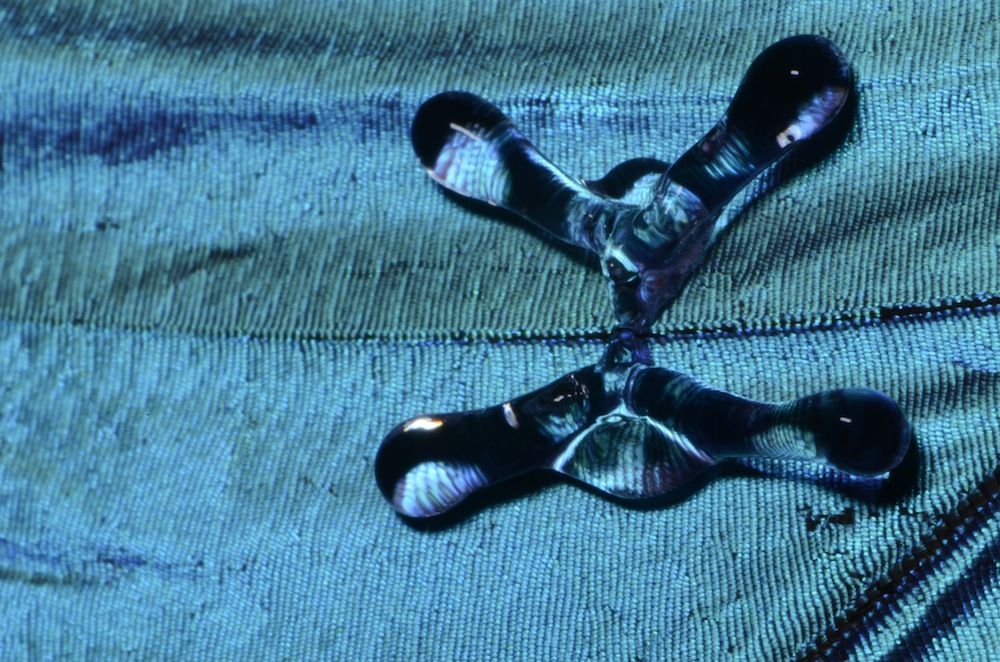

"We discovered that both the wings of the Morpho butterfly (Morpho didius) and the leaves of the nasturtium plant (Tropaeolum majus L.) have multiple superhydrophobic ridges, or veins, on a similar scale to our macro-textured surfaces," the authors write in the research article describing the new technique today (Nov. 20) in the journal Nature.

The new materials could have multiple applications. In addition to waterproofing sporting gear and clothing, the new approach could be used for keeping airplane wings from becoming icy and improving the aerodynamics of minuscule robots flying in the rain.

"We expect that this approach could be extended to surfaces exposed to freezing rain to prevent icing," the researchers write.

That's because the freezing of raindrops onto a surface takes time, so reducing the contact time between the surface and the rain could reduce frost accumulation.

Follow Tia Ghose on Twitter and Google+. Follow LiveScience @livescience, Facebook & Google+. Original article on LiveScience.

Tia is the managing editor and was previously a senior writer for Live Science. Her work has appeared in Scientific American, Wired.com and other outlets. She holds a master's degree in bioengineering from the University of Washington, a graduate certificate in science writing from UC Santa Cruz and a bachelor's degree in mechanical engineering from the University of Texas at Austin. Tia was part of a team at the Milwaukee Journal Sentinel that published the Empty Cradles series on preterm births, which won multiple awards, including the 2012 Casey Medal for Meritorious Journalism.

Most Popular