'Neanderthal' Remains Actually Medieval Human

A few fragmentary bones thought to be the remains of Neanderthals actually belonged to medieval Italians, new research finds.

The study is a reanalysis of a tooth, which was found in in a cave in northeastern Italy along with a finger bone and another tooth. Originally, researchers identified these scraps as belonging to Neanderthals, the early cousins of humans who went extinct about 30,000 years ago. Instead, the new study reveals the bones to belong to modern Homo sapiens.

There's no telling whom the original owner of the teeth and finger was, but the cave where they were discovered was both a hermitage, or dwelling place, and the site of a grisly medieval massacre. [8 Disturbing Archaeological Discoveries]

Mystery find

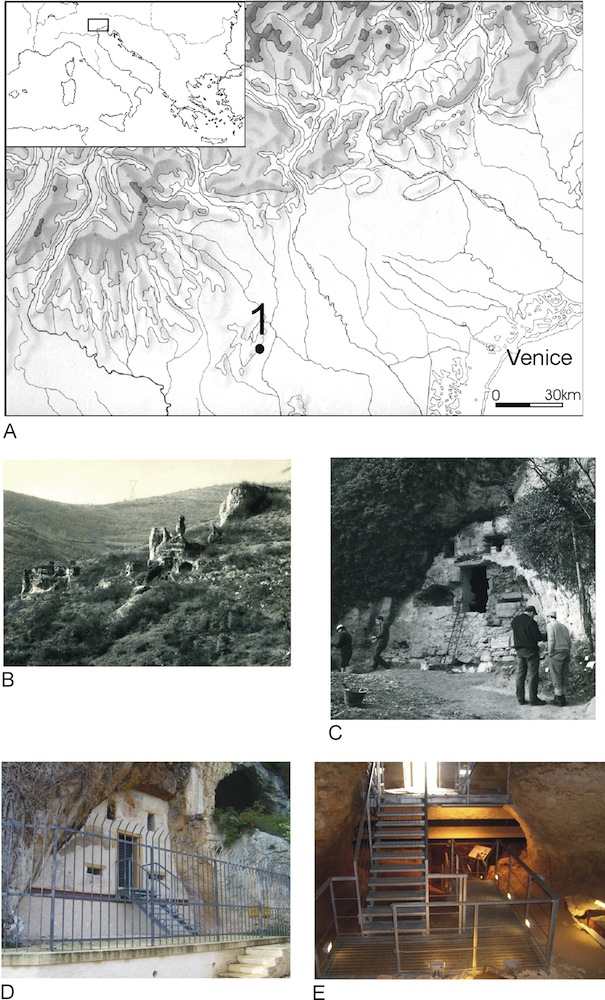

The teeth and the bone were found in the San Bernardino Cave in the 1980s in a rock layer dating back to Neanderthal times, approximately 28,000 to 59,000 years ago. But location alone is not enough for a firm identification, said study researcher Stefano Benazzi, a physical anthropologist at the Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology in Germany. An analysis of the bones themselves is necessary, too. Earlier, researchers had conducted this analysis, but they lacked the high-tech tools available to scientists today.

"The taxonomical discrimination of the species was based mainly on the layer the human fossil was found instead of the morphological features," or shape and size of the bones, Benazzi told LiveScience.

The size and shape of the teeth were consistent with belonging to Homo sapiens, but their rock layer suggested Neanderthal. A look back at the excavations revealed murky geology — at some point in the late middle ages, a wall to seal off the cave had been built, potentially disturbing the rock layers and preventing the researchers from using the layers as proof of age.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Human or Neanderthal?

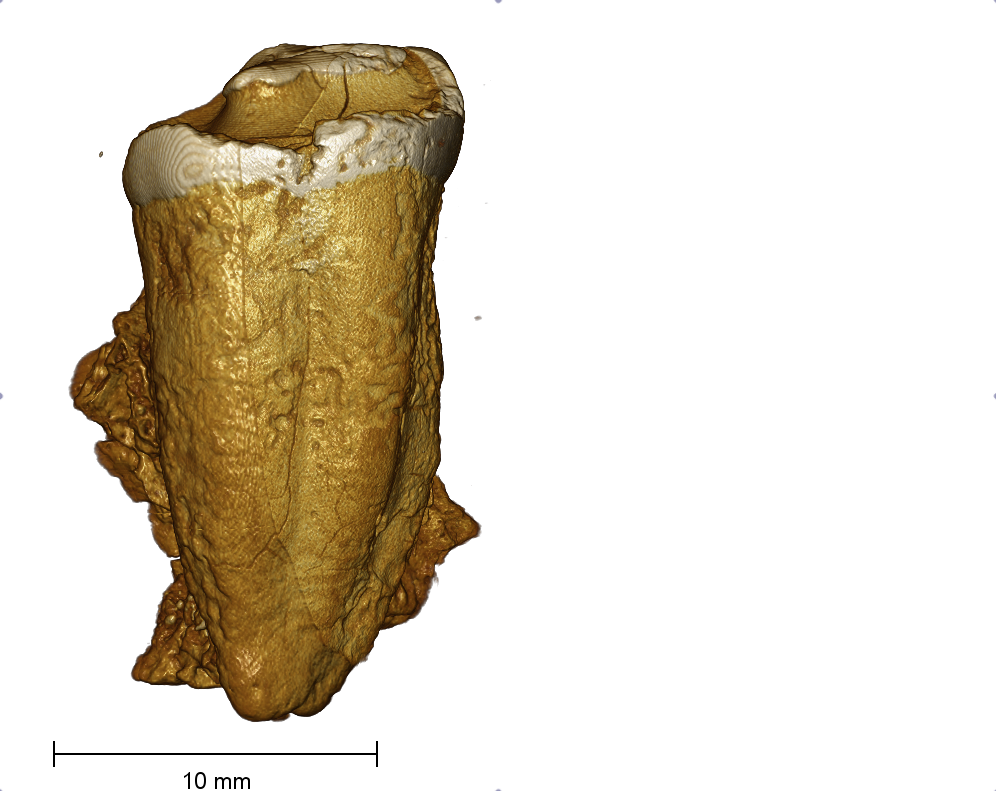

Benazzi and his colleagues took a direct approach, analyzing one of the teeth, a molar, found in the cave. (These analyses require the destruction of part of the bone, which is why they are often not done.)

First, they took a look at the shape of the tooth using micro-computed tomography (CT), a scanning method that allows researchers to create virtual 3D models of an object. They also sampled for mitochondrial DNA, a type of DNA passed down the maternal line. Next, they used radiocarbon dating to determine the age of the tooth. Finally, they analyzed molecular traces in the tooth to determine the individual's diet. [In Photos: New Human Ancestor Possibly Unearthed in Spanish Cave]

The results converged on one answer: This tooth was not Neanderthal. The shape was somewhat ambiguous, but suggestive of a Homo sapiens' tooth. The DNA looked far more human than Neanderthal. The date sealed the deal: Instead of being at least 30,000 years old, the tooth dated back to between A.D. 1420 and 1480.

The diet analysis revealed that the ratio of plants and meat eaten by the tooth's owner was consistent with the diet of a medieval Italian who ate millet, a plant not even introduced to Italy until 5,000 years ago or later.

"It's great that technology has advanced so far now that we can reassess these older finds," said Kristina Killgrove, a biological anthropologist at the University of West Florida who was not involved in the study. "Now we can use carbon-14 dating and ancient DNA and compare it to the Neanderthal genome."

Though the researchers did not chemically analyze the other tooth and finger bone, their sizes and close association with the molar suggest that they, too, are medieval in origin.

A grisly history

The discovery of medieval bones highlights the cave's long history. It served as a hermitage in the 1400s, and was possibly inhabited by San Bernardino of Siena, a priest and missionary who spent time in the area. In 1510, during the War of the League of Cambrai, the cave was a site of a massacre of local people by mercenary troops. Some died of asphyxiation in the cave itself, where they had fled to seek refuge.

Whether the bones belong to one of those victims or to another medieval Italian is unknown, but the construction of a wall over the cave mouth in the Late Middle Ages likely pushed the bones into the deeper rock layers, where they were mistaken for Neanderthal remains. After the massacre, the site became a church.

The re-categorization of the bones also shows that anthropology should not focus only on new finds, but also needs to look back at old discoveries, Benazzi said.

"We show that a lot of fossils discovered in the past, San Bernardino as an example, need to be reassessed," he said. That work is ongoing, he added, and his research group is working to analyze other remains found in other caves.

The findings will be reported in an upcoming issue of the Journal of Human Evolution.

Follow Stephanie Pappas on Twitter and Google+. Follow us @livescience, Facebook & Google+. Original article on LiveScience.

Stephanie Pappas is a contributing writer for Live Science, covering topics ranging from geoscience to archaeology to the human brain and behavior. She was previously a senior writer for Live Science but is now a freelancer based in Denver, Colorado, and regularly contributes to Scientific American and The Monitor, the monthly magazine of the American Psychological Association. Stephanie received a bachelor's degree in psychology from the University of South Carolina and a graduate certificate in science communication from the University of California, Santa Cruz.