Ancient Nordic Grog Intoxicated the Elite

Ancient Scandinavians quaffed an alcoholic mixture of barley, honey, cranberries, herbs and even grape wine imported from Greece and Rome, new research finds.

This Nordic "grog" predates the Vikings. It was found buried in tombs alongside warriors and priestesses, and is now available at liquor stores across the United States, thanks to a reconstruction effort by Patrick McGovern, a biomolecular archaeologist at the University of Pennsylvania Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology and Delaware-based Dogfish Head Craft Brewery.

"You'd think, with all these different ingredients, it sort of makes your stomach churn," McGovern, the study's lead author, told LiveScience. "But actually, if you put it in the right amounts and balance out the ingredients, it really does taste very good."

Drink of the ancients

McGovern began the journey toward uncovering the ingredients of ancient Nordic alcohol decades ago, when he began combing through museums in Denmark and Sweden, looking for pottery shards that held traces of old beverages. But in the mid-1990s, the technology to analyze these chemical remnants just wasn't available, he said. [See Images of Nordic Graves and the Artifacts]

More recently, McGovern and his co-authors re-examined the remnants with modern tools. They analyzed samples from four sites, two of which were grave sites in Sweden and Denmark. The oldest of these sites dated back to 1500 B.C. — more than 3,500 years ago. The oldest sample came from a large jar buried with a male warrior in Denmark. The other three came from strainer cups, used to serve wine, found in Denmark and Sweden. One of the strainer cups came from a tomb where four women were buried. One of the women, who died at around age 30, clutched the strainer in her hand.

Beer brewing goes back at least 10,000 years, and ancient humans were endlessly creative in their recipes for intoxicants. Studies of pollen content in northern European drinking vessels suggested the ancient residents drank honey-based mead and other alcoholic brews. But the exact ingredients were not well understood. Ancient texts written by Greeks and Romans proved that southern Europeans were among the first wine snobs — these authors dismissed Northern beverages as "barley rotted in water."

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

In fact, Nordic grog was a complex brew, McGovern and his colleagues found. The ingredients included honey, cranberries and lingonberries (acidic red berries that grow in Scandinavia). Wheat, rye and barley — and, occasionally, imported grape wine from southern Europe — formed a base for the drink. Herbs and spices — such as bog myrtle, yarrow, juniper and birch resin — added flavor and perhaps medicinal qualities.

The oldest sample, which was buried with a male warrior, was an anomaly. The jug found in that grave contained only traces of honey, suggesting that the occupant went to his grave with a jar of unadulterated mead. Because the warrior had well-crafted weapons in his tomb, he was likely of high status. Pure mead was probably a drink for the elite, because honey was expensive and scarce, the researchers reported online Dec. 23 in the Danish Journal of Archaeology. [Raise your Glass: 10 Intoxicating Beer Facts]

Delicious brew

The grog was likely a high-class beverage, McGovern said. In the 1920s, archaeologists uncovered a remarkably well-preserved burial of a young blond woman in Denmark. Dubbed "Egtved Girl" (pronounced "eckt-VED"), the corpse was buried wearing a wool string skirt with a bucket of grog at her feet. The young woman's clothes and ornaments suggest that she was a priestess who likely danced in religious ceremonies, McGovern said.

In other graves, wine-serving kits imported from southern Europe are also associated with women, McGovern said.

"That gives the impression that the women were the ones who would make the beverages in antiquity, and they were the ones that would serve it to the warriors," he said.

The imported wine strainer cups and traces of grape wine, which was only produced in southern Europe, suggest a robust trade network in this period, McGovern said. Northerners likely shipped Baltic amber southward in return for the wine and drinking utensils.

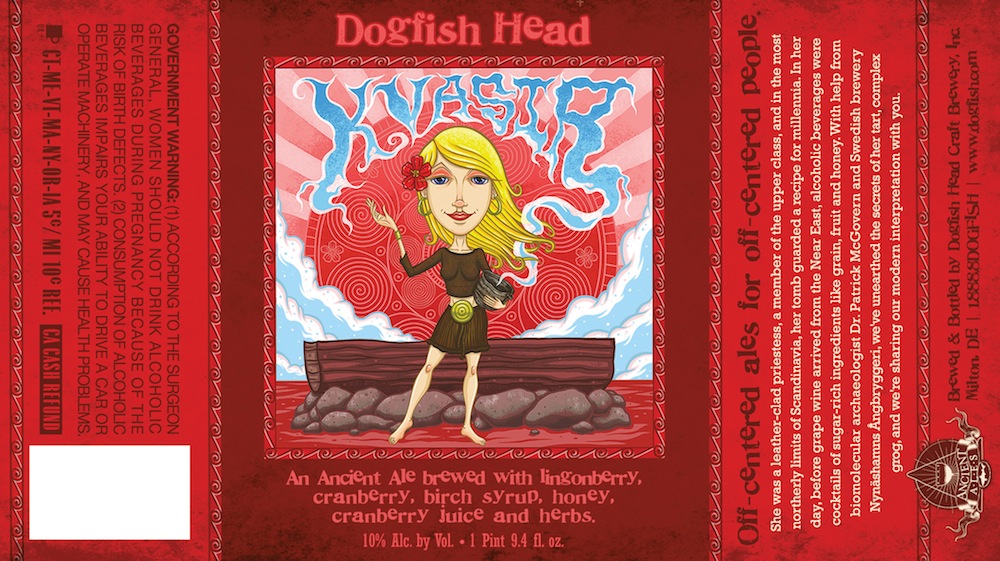

With McGovern's help, Dogfish Head recreated the Nordic grog in October 2013, using wheat, berries, honey and herbs. The only difference was that Dogfish Head's brew contains a few hops, the bittering agents used in most modern beers. Hops weren't used in beers in Europe until the 1500s.

Dogfish Head's grog is called Kvasir, a name that hints at its roots. In Nordic legend, Kvasir was a wise man created by gods spitting into a jar. Two dwarfs later murdered Kvasir and mixed his blood with honey, creating a beverage that was said to confer wisdom and poetry onto the drinker.

The grog tastes sour, like a Belgian lambic, McGovern said. But there are other options available to those who want a taste of Bronze Age Europe. The Swedish brewery Nynäshamns Ångbryggeri created another version of grog called Arketyp, and it is available at state liquor stores in Sweden. And on the Swedish island of Gotland, locals still brew a mixture of barley, honey, juniper and herbs that tastes much like what their ancient ancestors drank.

Follow Stephanie Pappas on Twitter and Google+. Follow us @livescience, Facebook & Google+. Original article on LiveScience.

Stephanie Pappas is a contributing writer for Live Science, covering topics ranging from geoscience to archaeology to the human brain and behavior. She was previously a senior writer for Live Science but is now a freelancer based in Denver, Colorado, and regularly contributes to Scientific American and The Monitor, the monthly magazine of the American Psychological Association. Stephanie received a bachelor's degree in psychology from the University of South Carolina and a graduate certificate in science communication from the University of California, Santa Cruz.