5 Ways Your Emotions Influence Your World (and Vice Versa)

Physical emotion

Emotions matter. Happiness, sadness, anxiety and anger all color our days and have a huge impact on how we feel about our lives.

But emotion reaches beyond the realm of feeling and influences people in ways far less obvious than might be expected. In this realm of "embodied cognition," social scientists are finding that the body influences the mind and the mind influences the body. Even the words people use to describe an experience have physical consequences.

Here are a few examples of how the physical and the mental influence one another.

Love is sweet

The sugar explosion around Valentine's Day is no coincidence. Research published in January 2014 finds that being in love makes food and drink — even tasteless distilled water — seem sweeter.

The finding illustrates how some rhetorical flourishes ("sweetheart," for example) have roots in the body. Study researcher Kai Qin Chan, a doctoral candidate at Radboud University Nijmegen in the Netherlands, suspects that the association between sweetness and love starts early, when babies learn to associate their parents' love with formula or breast milk.

Importance is heavy

Giving someone a heavy clipboard can make them think job candidates are more serious than someone holding a light clipboard, according to a 2010 study. The seriousness-heaviness link works the other way around, too. In research published in January 2011, psychologists told people a book was full of either important information or fluff. When asked to judge the weight of the book, participants thought it was heavier if they'd been told it was full of important writing.

Powerlessness is, too

Importance isn't the only thing that makes objects feel heavy. Powerlessness does, too.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

People induced to feel powerless, either by writing about a vulnerable experience or assuming a weak physical pose, are more likely to feel like objects are heavier than people who don't feel powerless, researchers reported in February 2014 in the Journal of Experimental Psychology. The effect may keep powerless people from overextending themselves, given that they don't control resources like a powerful person does, study researcher Eun Hee Lee of the University of Cambridge told Live Science.

Loneliness is cold

"I've been frozen out at work." "She greeted me with warmth." It's clear that English-speakers link social interaction with warmth, and loneliness and isolation with cold. Turns out, people feel it in their very bones.

In research published in 2008, scientists induced loneliness or feelings of acceptance in volunteers by asking them to remember a time they'd been excluded or included. They then asked them to estimate the temperature in the room.

Those induced to feel loneliness estimated the room to be 4 degrees Fahrenheit colder, on average, than those who were feeling accepted. In a follow-up study, researchers found that people excluded from a game were more drawn to warm foods like soup, presumably trying to warm their bodies in compensation for the chill of loneliness.

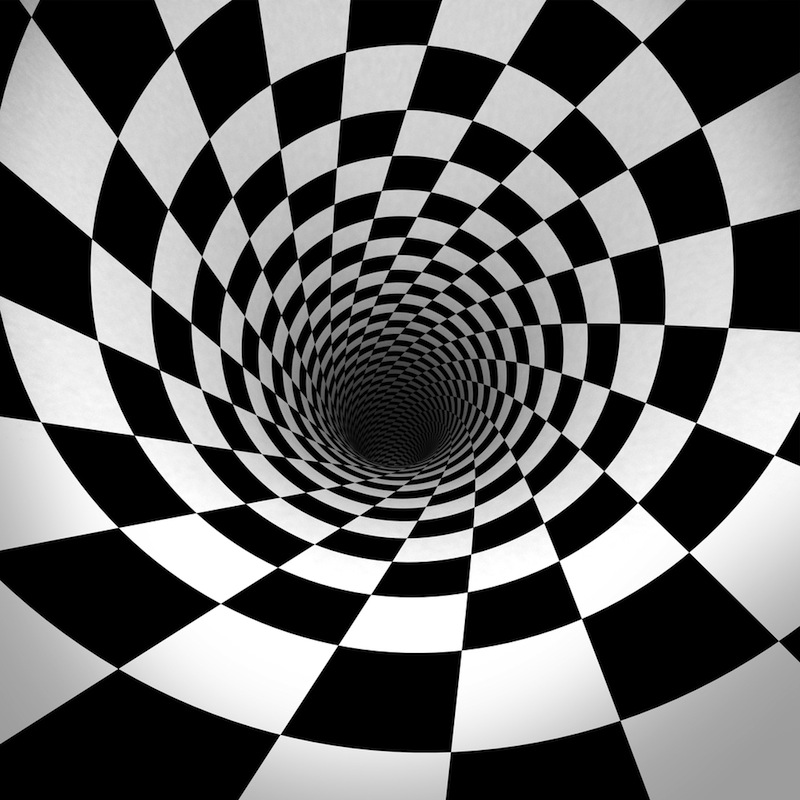

Black-and-white makes you judgmental

Sometimes the metaphor influences the emotions. Studies show, for example, that holding a warm beverage makes people see strangers as warmer and more friendly.

In an even weirder example, seeing information in black-and-white can literally make people's judgments more black-and-white, researchers reported in 2012. When given a moral dilemma printed with a black-and-white border, people were more likely to make a strong judgment of morality or immorality. When the border was gray or colorful, participants were more likely to see both sides of the story.

Stephanie Pappas is a contributing writer for Live Science, covering topics ranging from geoscience to archaeology to the human brain and behavior. She was previously a senior writer for Live Science but is now a freelancer based in Denver, Colorado, and regularly contributes to Scientific American and The Monitor, the monthly magazine of the American Psychological Association. Stephanie received a bachelor's degree in psychology from the University of South Carolina and a graduate certificate in science communication from the University of California, Santa Cruz.