Who was Genghis Khan, the warrior who founded the Mongol Empire?

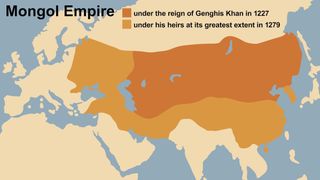

Genghis Khan (1160 to 1227) founded the Mongol Empire, which covered much of Asia and parts of Europe.

Genghis Khan was a 13th-century warrior in central Asia who founded the Mongol Empire, which stretched from the Pacific Ocean to Europe.

Much about Genghis Khan remains unknown. For instance, we don't really know what he looked like, because not a single authentic portrait of the man survives to the present day, Jean-Paul Roux, who was a professor emeritus at the Ecole du Louvre, wrote in his book "Genghis Khan and the Mongol Empire" (Thames & Hudson 2003). All images of him that exist today were created after his death or by people who never met him.

Additionally, until Genghis Khan gained control over the Uyghur people, the Mongolians did not have a writing system. As such, many surviving records of him were written by foreigners. One important Mongolian record, called "The Secret History of the Mongols," was written anonymously (as its name suggests) sometime after Genghis Khan's death.

When did Genghis Khan live?

From what modern-day historians can gather, Genghis Khan was born sometime around A.D. 1160 (the exact year is uncertain) and died in August 1227, possibly of bubonic plague, while waging a campaign against the Tangut people.

Genghis Khan's Early Life and Wives

Genghis Khan was born with the name Temüjin (also spelled Temuchin). At the time, Mongolia was not unified and was ruled by different clans and tribal groups. His father, named Yesüge (also spelled Yesükai), "was lord and leader of 40,000 tents or families. Even his brothers, including those senior to him, acknowledged him as their leader and head of the Borjigin clan," Syed Anwarul Haque Haqqi, who was a professor at Aligarh Muslim University in India, wrote in his book "Chingiz Khan: The Life and Legacy of an Empire Builder" (Primus Books, 2010).

Temüjin's mother, Hoelun, had been captured by his father's clan and forced to become Yesügei's wife (a common practice in Mongolia at the time). Their son was named Temüjin to celebrate his father's triumph over an enemy who was also called Temüjin, Haqqi wrote, noting that it was common to name a newborn child after an auspicious event.

We know little of Temüjin's early life, "but it is reasonable to suppose that as the years rolled by and childhood turned into youth [he] was brought up in the hard and harsh atmosphere of nomadic life, in which the tribal lords and chiefs fought, drank, and duelled, married and slept with their weapons underneath them — a rigorous life in which chiefs shared the miseries, hungers and privations of their people," Haqqi wrote.

Around age 9, Temüjin was betrothed to Börte, the 10-year-old daughter of Dai Sechen, the leader of the Jungirat tribe (there are different spellings of these names). At some point, Temüjin's father died (apparently poisoned), and the family's power faded as many of his father's followers deserted them.

Temüjin, his family and their remaining followers were forced to eke out a living on marginal pasturelands, contending with thieves and old rivals of Yesügei hoping to kill his family. Around age 14, Temüjin murdered his half brother Bekter according to "The Secret History of the Mongols." This may have arisen from a dispute over resources. After a few years, Temüjin was able to marry Börte, and she became the most prominent of his multiple wives.

Genghis Khan's army and empire

Around 1200, Temüjin and his friend Toghrul launched a campaign against the Tatars, a group that lived in parts of what are now Mongolia and China, and whom they defeated in 1202. The two would later have a falling out, and Toghrul was killed after Temüjin defeated his forces.

By 1206, Temüjin had conquered most of Mongolia, and the remaining tribes were forced to acknowledge him as their leader. He took the name Genghis Khan, which has a few different translations, one of which is "oceanic sovereign," Roux wrote.

Genghis Khan then launched a successful campaign against the Jin dynasty, taking northern China. Historical records indicate that by 1234, the population of northern China had dropped by two-thirds due to war, Jinping Wang, an associate professor of history at the National University of Singapore, wrote in her book "In the Wake of the Mongols: The Making of a New Social Order in North China, 1200-1600" (Harvard University Asia Center, 2018).

Jinping Wang holds a PhD from Yale University (2011) and is a social-cultural historian of pre-modern China. She specializes in Chinese history, Chinese religions, regional studies, and the Mongol-Yuan and Ming Empires.

Her monograph, "In the Wake of the Mongols: The Making of a New Social Order in North China, 1200-1600" describes how northern Chinese people interacted with their Mongol conquerors to create a drastically new social order.

He then turned his attention westward, moving deeper into central Asia. In 1219, Genghis Khan launched a successful campaign against the shah of Khwarezm (based in modern-day Iran), whose kingdom was suffering from internal disputes, David Morgan, who was a professor emeritus at the University of Wisconsin-Madison, wrote in a paper published in the book "The Coming of the Mongols" (London Middle East Institute, 2018). Genghis Khan's campaigns caused so much death and destruction that there was a small drop in global carbon dioxide emissions.

The use of cavalry and the composite bow were important, as they provided the Mongols with excellent mobility Timothy May, professor of central Eurasian history at the University of North Georgia, wrote in his book "The Mongols" (Arc Humanities Press, 2019). Research indicates that Mongolia's climate was wetter than normal, allowing for more grass to grow and thus more horses to graze.

Timothy May specializes in the history of the Mongol Empire and is the author and editor of six books, over 30 articles and chapters and numerous other publications. He is also the editor of Mongolian Studies: The Journal of the Mongolia Society.

As Genghis Khan took over more land, he made innovations in the form of government and organization. "Once he had conquered territories beyond Mongolia, he instituted a more sophisticated administrative structure and a regular system of taxation," Morris Rossabi, an associate adjunct professor in the Department of East Asian Languages and Cultures at Columbia University, wrote in a section of the book "Genghis Khan and the Mongol Empire" (University of Washington Press, 2009). "Recruiting captured Turks, Chinese and others, he began to devise a more stable system that could contribute to a more orderly government, with specialized official positions."

He devised a system of laws and regulations. "In accordance and agreement with his own mind he established a rule for every occasion and a regulation for every circumstance; while for every crime he fixed a penalty," the Persian writer Ata-Malik Juvayni, who lived in the 13th century, wrote in his book "History of the World Conqueror" (translated by John Andrew Boyle in 1958).

Genghis Khan said that plunder from his campaigns must be shared among his troops and insisted they follow a vigorous training routine focused on hunting. This was "not for the sake of the game alone, but also in order that they may become accustomed and inured to hunting and familiarized with the handling of the bow and the endurance of hardships," Juvayni wrote.

He ordered his troops not to harm artisans and to leave clerics alone, respecting people of other faiths. Genghis Khan himself followed a system of beliefs that revolved around Mongolian shamanism, according to historical records.

Genghis Khan's death and tomb

Genghis Khan died in 1227, amid a campaign against the Tangut people. His tomb has never been found, and texts written during his lifetime are virtually silent about its location.

After Genghis Khan's death, his son Ogedai (also spelled Ögedei or Ögodei) ruled over the Mongols until he died in 1241. Ultimately, the Mongol Empire did not remain unified, falling into civil war after the death of Möngke Khan, a grandson of Genghis Khan, in 1259.

Additional resources

The Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York City has an article that looks at the legacy of Genghis Khan. The National Palace Museum in Taiwan has several portraits showing Genghis Khan and his descendants. But these paintings were completed after Genghis Khan's death and may not reflect how he looked in life. An attempt was made to find the tomb of Genghis Khan through satellite survey. It was unsuccessful but its results were published in an article in the journal PLOS One.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Owen Jarus is a regular contributor to Live Science who writes about archaeology and humans' past. He has also written for The Independent (UK), The Canadian Press (CP) and The Associated Press (AP), among others. Owen has a bachelor of arts degree from the University of Toronto and a journalism degree from Ryerson University.