New Maps Show How Habitats May Shift with Climate Change

As regional temperatures shift with climate change, many plants and animals will need to relocate to make sure they stay in the range of temperatures they're used to.

For some species, this shift will mean a fairly direct adjustment toward higher latitudes to stay with cooler temperatures, but for many others, the path will take twists and turns due to differences in the rate at which temperatures change around the world, scientists say.

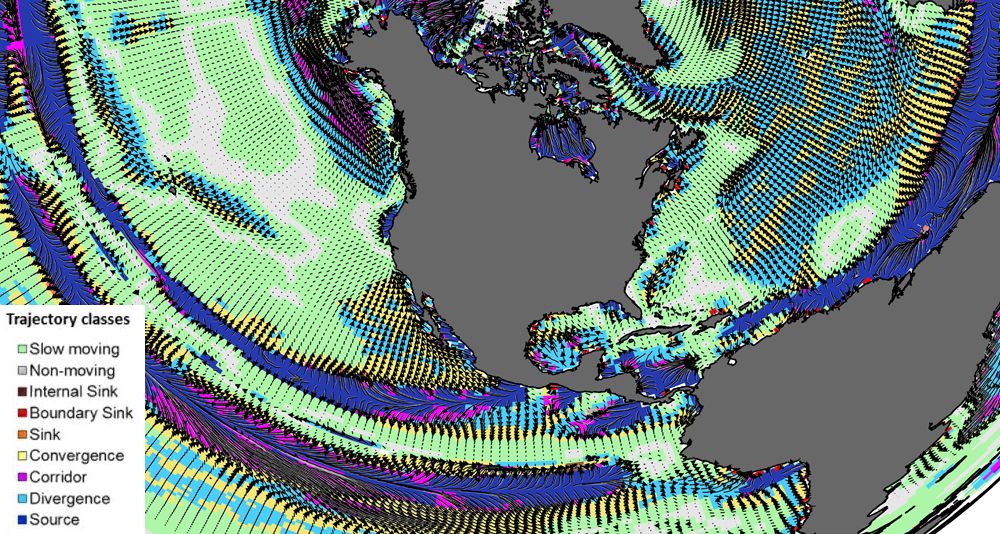

Now, a team of 21 international researchers has identified potential paths of these twists and turns by mapping out climate velocities— the speed and intensity with which climate change occurs in a given region — averaged from 50 years of satellite data from 1960 through 2009, and projected for the duration of the 21st century.

"We are taking physical data that we have had for a long time and representing them in a way that is more relevant to other disciplines, like ecology," said co-author Michael Burrows, a researcher at the Scottish Marine Institute. "This is a relatively simple approach to understanding how climate is going to influence ocean and land systems."

Where species come and go

The resulting maps indicate regions likely to experience an influx or exodus of new species, or behave as a corridor or, conversely, a barrier, to migration. Barriers, such as coastlines or mountain ranges, could cause local extinctionsif they prevent species from relocating, the team says. [Maps: Habitat Shifts Due to Climate Change]

"For example, because those environments are not adjacent to or directly connected to a warmer place, those species from warmer places won't be able to get there very easily," Burrows told Live Science. "They might still get there in other ways, like on the bottoms of ships, but they won't get there as easily."

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Warming waters and changes in regional ocean currents have already caused the long-spined sea urchin, previously only found as far south as southern New South Wales in Australia, to migrate farther south along the eastern Tasmanian coast, co-author Elvira Poloczanska, of Australia's Commonwealth Scientific and Industrial Research Organization, said in a statement. The urchins have decimated kelp forests in the region, demonstrating the domino effect that temperature changes can have in regional ecosystems.

The researchers hope the maps will help conservation biologists predict where certain species will migrate in the future, and help management organizations devise conservation plans accordingly.

The maps' accuracy has some limitations, though. For example, the study only assesses changes in temperature, and excludes other factors that determine habitat ranges, such as precipitation and species interactions. The maps also have a limited spatial resolution of only 1 degree latitude by 1 degree longitude, which may not distinguish between certain types of environments like the tops of mountains and neighboring areas, Burrows said.

Deceiving appearances

Tony Barnosky, a researcher at the University of California, Berkeley who studies global ecological change but was not involved in this study, recognizes these limitations, but he still thinks the maps provide a helpful step forward.

"Temperature is a good place to start, because it is fairly straightforward to get those measurements, and we know that many species have this very rough correlation with temperature boundaries," Barnosky told Live Science. "It would also be useful to have these kinds of studies for things like precipitation and number of hot days in a year, but that is a scale of data and resolution that is much harder to get, so I think this sort of study is a good way to enter into the problem."

The study is also helpful for identifying regions that might not appear to be undergoing change but that are susceptible to passing thresholds of rapid change sooner than other regions, Barnosky said. Some mountainous regions, such as the Andes and the Himalayas, for example, appear to be experiencing slower rates of change than flat-lying, inland regions like the Australian Outback, according to the report.

The study findings were detailed Feb. 10 in the journal Nature.

Follow Laura Poppick on Twitter. Follow us @livescience, Facebook & Google+. Original article on Live Science.