An ancient whale used sound beams to navigate and stalk prey 28 million years ago, an analysis of a new fossil suggests.

The new whale species, called Cotylocara macei, contains air pockets in the skull similar to those used by porpoises and dolphins to send out focused sound beams. The discovery pushes back the origins of the ability, called echolocation, to at least 32 million years ago, said study co-author Jonathan Geisler, an anatomist at the New York Institute of Technology.

"It suggest echolocation evolved very, very early in the history of the group that involved toothed whales," a group that includes sperm whales and killer whales, as well as dolphins and porpoises, Geisler said. [Image Gallery: Russia's Beautiful Killer Whales]

Fossil whale

About 10 years ago, scientists unearthed a complete toothed whale skull, along with a few neck vertebrae and some ribs in a fossil-rich region near Charleston, S.C. An international collector named Mace Brown acquired the find, and then invited Geisler to take a look at it. (The new species is named after the collector.)

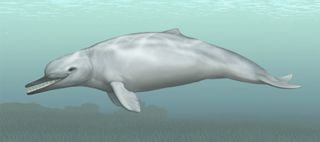

The ancient whale, which was about 28 million years old, grew to about 10 feet (3 meters) long and looked somewhat similar to modern-day dolphins or small cetaceans, though they are not closely related. It likely lived in shallow marine environments, such as the mouth of an estuary or a little further offshore, Geisler said.

Early echolocation

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

C. macei also had several distinctive features, including bone density variations and several deep air cavities, including one on top of the skull and one on either side of the base of the snout, Geisler said.

Those air sinuses looked similar in purpose to those found in toothed whales, or odontocetes. In odontocetes, the air sinsuses help them form nearly continuous, focused sound beams to investigate or search for prey in dark or muddy water. They then process the reflections of those sound beams through internal ears on the side of their heads, or through air spaces between their jaws, to create a sound-based map of the world around them.

"Odontocetes don't produce sound in their voice box, it's originated in the face," Geisler told Live Science.

The ear bones and soft tissue from the whale weren't preserved, so they don't know for sure how the whale's echolocation would have sounded or how it processed the reflections from sound beams they sent out, Geisler said.

The new discovery suggests that echolocation evolved very early in whale evolution, likely soon after odontocetes diverged from the ancestors of baleen whales.

The findings were published today (Mar. 12) in the journal Nature.

Follow Tia Ghose on Twitter and Google+. Follow Live Science @livescience, Facebook & Google+. Original article on Live Science.

Tia is the managing editor and was previously a senior writer for Live Science. Her work has appeared in Scientific American, Wired.com and other outlets. She holds a master's degree in bioengineering from the University of Washington, a graduate certificate in science writing from UC Santa Cruz and a bachelor's degree in mechanical engineering from the University of Texas at Austin. Tia was part of a team at the Milwaukee Journal Sentinel that published the Empty Cradles series on preterm births, which won multiple awards, including the 2012 Casey Medal for Meritorious Journalism.

Most Popular